Introduction

Background and rationale

Ko te tākaro te kauwaka e pakari ake ai te tangata | Cultural pluralism for play-based pedagogy emerges at the intersection of culturally sustaining pedagogies and playbased learning.

These are two pedagogical approaches that have been gathering momentum in the primary Aotearoa New Zealand school context over the past decade with mixed understanding, confidence, and quality of practice implementation. In this context, cultural pluralism refers to an educational environment where diverse cultural groups participate fully in the learning community while maintaining their distinct identities and traditions. Rather than expecting assimilation into dominant norms, cultural pluralism values belonging without erasure, what Kallen (1924) described as a symphony of coexisting identities, each retaining its integrity while contributing to a shared civic culture. Within Aotearoa New Zealand’s education system, this stands in direct contrast to “whitestream” schooling, where Māori learners are often expected to navigate educational spaces stripped of cultural relevance or recognition (Milne, 2013, 2016, 2020). Milne argues that “white spaces can be coloured in” through practice that gives voice to community, centres cultural knowledge, and conscientises whānau to resist the status quo. In this project, cultural pluralism serves not as a neutral descriptor, but as a transformative stance. One that underpins the integration of culturally sustaining pedagogy and indigenised play practice as a means of educational justice.

Culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP) refers to an approach that seeks to not only affirm but also sustain the cultural identities, languages, and practices of students while fostering academic success (Paris & Alim, 2017). It builds on the foundational work of culturally sustaining teaching (Gay, 2010) and Indigenous education frameworks (Penetito, 2010), advocating for an education system where the cultural capital of diverse learners is actively incorporated into teaching and learning. In the Aotearoa New Zealand context, CSP aligns with kaupapa Māori education principles, reinforcing the importance of relational and collective learning experiences.

Play-based learning (PBL) is an educational approach that positions play as a central medium for children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development. It is underpinned by constructivist theories of learning (Piaget, 1962; Vygotsky, 1978) and is recognised for its role in fostering creativity, problem solving, and social competence in young learners (Hedges, 2018). In Aotearoa New Zealand, PBL has been increasingly embraced in early childhood and primary settings as an approach that honours child-led inquiry, holistic development, and meaningful engagement with the curriculum.

When these two pedagogies are brought together, they create opportunities to embed Indigenous knowledge systems, values, and aspirations within child-centred learning approaches, responding to the need to address systemic racism and indigenise primary school curricula in Aotearoa New Zealand. As the popularity of PBL rises, there remains a critical gap in research that considers how Indigenous conceptualisations of play and CSP can be effectively integrated into mainstream educational settings.

There is a growing body of literature on play pedagogy in New Zealand primary schools (Aiono, 2020; Aiono et al., 2019; Davis, 2015; Hedges, 2018); however, much of this research is grounded in Western theories of child development. Less attention has been given to how mātauranga Māori — Māori knowledge systems rooted in whakapapa, whenua, tikanga, and relational ways of being — can inform and transform classroom practice (Penetito, 2010; Smith, 1999). Within mātauranga Māori, ira tākaro (schemas of play) are seen as powerful, embodied expressions of tamariki development. These expressions supported skill acquisition, cultural transmission, identity formation, and social learning long before the introduction of colonised schooling systems (Brown & Brown, 2022). Yet colonisation disrupted these rich and holistic learning environments, replacing them with models that often failed to recognise relational, spiritual, and cultural dimensions of play. Contemporary work by Brown and Brown (2022) argues that these play expressions remain “pronounced and packed with powerful potential” but are often “maligned and misunderstood” by educators unfamiliar with their cultural framing (p. 17). Similarly, community-based initiatives such as those led by Healthy Families Rotorua are revitalising traditional Māori play practices like manu aute and māra hūpara, embedding mātauranga Māori in play environments that support holistic wellbeing, intergenerational learning, and cultural reconnection (Lacey, 2021). These examples highlight that mātauranga Māori is not only a theoretical foundation but a living, generative system informing how tamariki learn, grow, and connect today.

This project, developed in partnership with Te Whai Hiringa – Peterhead School, Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated, Massey University, and Longworth Education Ltd, sought to develop an indigenised framework for PBL that aligns with local iwi goals, supports tamariki in fostering a strong cultural identity, and enhances the professional learning of kaiako.

This project aimed to explore and understand Indigenous play pedagogies within the context of supporting tamariki Māori within mainstream education. To do this, we sought to develop and implement a culturally sustaining framework for play that would honour the aspirations of mana whenua, enhance tamariki sense of belonging and educational success, and ensure kaiako had the necessary supports to develop their confidence in growing their practice to achieve this. The project recognised the need for further support for schools in navigating the complexity of iwi, hapū, and whānau knowledge systems. Rather than layering a singular Indigenous view over existing practices, this research emphasised the importance of capturing the richness and variation within mātauranga Māori, acknowledging not only its diverse expressions but also the localised knowledge and tikanga that must be respected and integrated within school curricula.

Research objectives

Ko te tākaro te kauwaka e pakari ake ai te tangata is guided by the following key research questions:

- What are the perspectives and experiences of tamariki, whānau, kaiako, and iwi regarding play and its role in learning?

- How can play practices be used to reflect the school’s core values of manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, and māramatanga, and support culturally sustaining pedagogies?

- What professional learning and development supports do teachers need to implement culturally sustaining play pedagogies effectively?

- What impact do culturally sustaining play pedagogies have on tamariki’s sense of cultural connection, belonging, language, and identity as mana whenua?

Strategic importance

This project aligns with national and iwi-led educational strategies, particularly Ka Hikitia (Ministry of Education, 2020) and Te Tōpuni Tauwhāinga, the Ngāti Kahungunu Education Strategy (Isaac-Sharland, 2020). Both policies emphasise the importance of culturally relevant education that upholds te reo me ōna tikanga (language and customs) and promotes equitable learning outcomes for Māori learners. Ko te tākaro te kauwaka e pakari ake ai te tangata advances these priorities by integrating Indigenous knowledge into primary education ensuring that PBL is not just a pedagogical tool but also a means of strengthening cultural identity and academic success.

Furthermore, with the increasing recognition that mainstream educational approaches often perpetuate systemic inequities (Milne, 2020; Penetito, 2010), this project provides an opportunity to challenge and transform dominant narratives in education. By embedding Indigenous play philosophies within primary school curricula, the framework developed through this project has the potential to serve as a model for other kura (schools) seeking to centre Māori ways of knowing in their teaching practices.

Expected contributions

This project will contribute to the field of education in several key ways:

- Development of an indigenised play pedagogy framework: A practical, researchinformed tool that guides schools in implementing culturally sustaining PBL.

- Enhancement of teacher practice: Professional learning opportunities for kaiako to build their confidence and competence in integrating mātauranga Māori into play pedagogy.

- Strengthening of tamariki wellbeing and learning: Supporting tamariki to develop a strong sense of identity, belonging, and cultural connection through play.

- Policy and practice implications: Informing national education policy and professional learning development to better support Māori learners in mainstream education.

Through these contributions, this project aims to offer a transformative approach to primary education that not only supports the wellbeing and success of Māori learners but also sets a precedent for culturally sustaining teaching and learning across Aotearoa New Zealand.

Research design

School and community context

The research was conducted at Te Whai Hiringa, a high equity index school situated in Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand. Of the school’s overall population, 92% of students identified as Māori or Pacific Peoples, providing a strong foundation for exploring culturally sustaining pedagogies through te ao Māori. Prior to this project, Te Whai Hiringa had already embarked on a deliberate journey to decolonise its learning environment and embed CSP. Its involvement was therefore not random but grounded in an established, reciprocal partnership with the research team, consistent with the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) principle of practitioner–researcher collaboration. This context provided a strong foundation for exploring how play pedagogy and culturally sustaining practice could be integrated and extended. The project was intentionally designed to support and extend the school’s ongoing efforts, while providing a robust context for researching the development of an indigenised play framework. This partnership model, central to all TLRI-funded projects, ensured that the research was contextually grounded, co-led by practitioners, and informed by the lived realities and aspirations of the school community.

Iwi partnership and Kauwaka guidance

The project was underpinned by a formal, values-based partnership with Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated, established through ongoing relationships between school leadership, iwi representatives, and the research team. Central to this partnership was the involvement of Kauwaka, an iwi-established cultural advisory body responsible for the revitalisation of te reo Māori and tikanga across the region. Kauwaka provided essential guidance throughout the research process, ensuring mātauranga Māori was authentically embedded and tikanga-aligned approaches were upheld. This partnership was not tokenistic or consultative, but reflected a genuine commitment to co-constructing knowledge, consistent with kaupapa Māori research principles and the relational ethos of design-based research.

Participants

Of the 131 tamariki involved in the research, 76% identified as Māori, with participating whānau reflecting this cultural makeup. Among the six Years 0–2 educators, one identified as Māori and five as Pākehā/European. The school leadership team included one Māori/ Pākehā leader and one of European descent, while the three learning coaches included two Māori and one Pākehā. This diversity in adult participants allowed for reflection on the implementation of CSP from both within and outside Māori worldviews.

Design-based research approach

This research employed a design-based research (DBR) methodology, an iterative approach well suited for collaboratively developing, testing, and refining educational interventions within authentic classroom contexts (Anderson & Shattuck, 2012; Brown, 1992; Design-Based Research Collective, 2003). DBR involves ongoing cycles of design, implementation, observation, and revision (Barab & Squire, 2004), allowing researchers and practitioners to co-construct practical, responsive pedagogical frameworks. Additionally, DBR aligns strongly with Māori research methodologies, particularly kaupapa Māori approaches, through its emphasis on relationality, iterative learning, and authentic contexts (Bishop, 1996; G. H. Smith, 1992; L. T. Smith, 1999). In this project, practices such as whakawhanaungatanga (relationship building) and wānanga (collective knowledge sharing) ensured findings remained contextually grounded and culturally sustaining.

Research phases

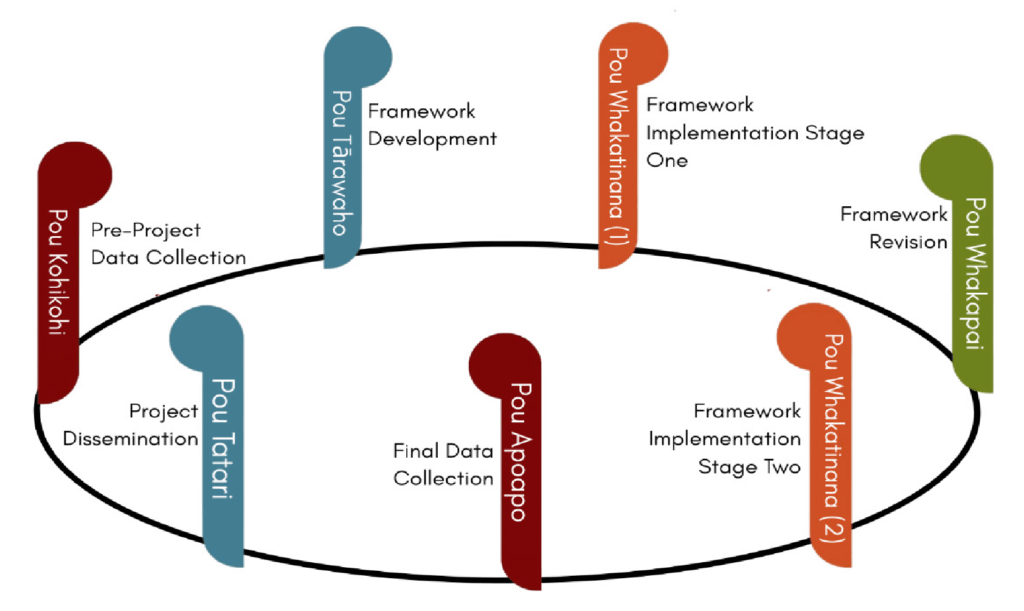

Figure 1 describes the iterative nature of the DBR methodology of this project. The research was conducted in multiple key phases to ensure an iterative and responsive approach to framework development. Initially, baseline teacher observations were conducted using the original version of the P-BLOT (Aiono & McLaughlin, 2018) and surveys adapted from the school’s previous use of Rongohia te Hau tools (Berryman et al., 2015), alongside surveys with kaiako and whānau and interviews with tamariki.

The framework development phase involved wānanga with project participants and project advisers. This included kōrero with a respected iwi elder closely connected to the school, who shared stories of his childhood play; consultation with iwi experts affiliated with Kauwaka regarding tikanga and play; and wider kōrero with project team members to unpack play through an Indigenous lens. Following this, an initial implementation period of the draft framework was conducted with kaiako, supported by PBC. The iterative nature of the research allowed for framework refinements based on insights gained during these stages.

A second wānanga was then held with project participants and co-lead investigators to problem solve implementation challenges and refine the framework. Adjustments were made based on kaiako feedback, and additional resources were identified to support further development. A second implementation phase continued this refinement and testing process before concluding with final data collection, analysis, and dissemination of findings.

Note: This graphic illustrates the cyclical and iterative phases (“pou”) of the research design, highlighting key stages including data collection, framework development, implementation, refinement, and dissemination within the Ko te Tākaro te Kauwaka e Pakari ake ai te Tangata project. [Original graphic created for this report.]

Data collection tools

PBL observations

Observations conducted during Pou Kohikohi used the P-BLOT (Aiono & McLaughlin, 2018), developed to assess play-based teaching practices. As part of this project, the P-BLOT underwent significant development to better reflect culturally sustaining, locally responsive pedagogical practice. The original tool (Aiono & McLaughlin, 2018) was revised collaboratively by the research team and community partners to include greater alignment with kaupapa Māori, specific teacher behaviours observable in Aotearoa New Zealand play-based classrooms, and a clearer articulation of culturally responsive pedagogy. As a result of this collaborative revision, the updated tool, Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro | The Play-based Learning Observation Tool (Aiono et al., 2024) was then used to conduct teacher observations during Pou Apoapo and to inform the coaching process throughout the project.

The following tables provide first a summary of structural changes (Table 1), followed by illustrative examples of revised and new indicators (Table 2) to demonstrate the impact of the research on observable teacher practices. While the full P-BLOT cannot be publicly reproduced due to commercial and copyright limitations, the following comparison outlines the depth and direction of its evolution.

| Domain | Original 2018 P-BLOT | Updated 2024 Ara Mātai Ako-ā- Tākaro P-BLOT |

Key shifts/Additions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Part A: Cultural connection and practice | Not present in original tool | New domain added. Focuses on the teacher cultural identity, responsiveness, and relationships with whānau and community. | Introduces culturally sustaining pedagogy as foundational;

reflects Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations and prioritises authentic partnership with Māori. |

| Part B: The learning environment | Previously Part A. Focused on pedagogical approaches to supporting PBL. | Expanded and reworded for greater specificity and cultural alignment. Some indicators merged or clarified. | Stronger emphasis on intentional design of environments that reflect

whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, and local cultural values. |

| Part C: Teacher behaviour | Previously Part B. Previously more generalised; few references to cultural models of behaviour guidance. | Refined to specify observable, measurable teacher actions aligned with Māori values such as ako, tika, and kotahitanga. | Greater emphasis on relational pedagogy, logical consequences, and collective responsibility; shifts from individualistic management to culturally grounded practice. |

| Part D: Overall teaching practices | Previously Part C.

Described general classroom routines, management, planning, and assessment strategies. |

Language updated

to reflect explicit instruction balanced with play. Expanded examples, stronger cultural framing, and safety/risk considerations. |

Highlights respect for resources (kaitiakitanga), clarity of routines,

and how teachers plan, document, and respond to learning within curriculum frameworks. |

| Part E:

Counterproductive practices |

Previously Part D.

Broad, generalised descriptors of practices inconsistent with play pedagogy. |

Expanded and

refined to include observable counterproductive behaviours and indicators that undermine culturally sustaining or playbased pedagogy. |

Provides clearer guidance on “what not to do”, supporting coaching, fidelity checking, and reflective practice. |

| Key definitions | Limited cultural contextualisation; primarily generic educational terminology. | Expanded definitions include te reo Māori terms and culturally rooted pedagogical concepts. | Enhances

accessibility for nonMāori educators while normalising Māori worldview and language within professional discourse. |

| Structure and scoring | Three-point

Likert scale: Little, Developing, Strong |

Retains 1–5 scale and Yes/No items, with additional indicators clarified and aligned with coaching and implementation tools. | Enables more consistent use in both research and professional development contexts. |

| Framing | Primarily pedagogical and descriptive; neutral research tone. | Explicitly grounded in kaupapa Māori principles; dual research and practice orientation. | Moves from neutral observation towards valuesaligned reflection, highlighting cultural obligations, equity, and bicultural commitments. |

Note: Table 1 summarises the structural and conceptual shifts between the 2018 Research Edition of the P-BLOT and the 2024 Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro P-BLOT. The updated version introduces a new domain on cultural connection and practice, reframes existing domains to embed culturally sustaining pedagogy, and refines indicators to reflect observable teacher behaviours aligned with Te Tiriti o Waitangi and Māori values. This enhanced version of the P-BLOT, now titled Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro: The Play-Based Learning Observation Tool (Aiono et al., 2024) has been used across the research settings to both measure and support teaching practice. Its development reflects a dual research–practice commitment to honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi, embedding mātauranga Māori, and enabling teacher reflection that is both evidence-informed and culturally grounded.

Examples of indicator revisions in the P-BLOT

To illustrate how the research process informed the refinement of the P-BLOT, Table 2 provides examples of how indicators were revised between the 2018 and 2024 versions. These examples highlight the strengthened emphasis on culturally sustaining pedagogy, the increased specificity of teacher behaviours, and the inclusion of practices that may undermine culturally sustaining play pedagogy. They are offered as illustrative examples only, designed to give readers a sense of how the tool supports observable, practicebased change, without publishing the full instrument.

| Revised indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2018 Version | 2024 Version | Key shift/addition |

| A3. Loose parts available for play. | B3. Loose parts available reflecting diverse cultural backgrounds and schema. | Greater cultural relevance, identity expression, and responsiveness to schema. |

| B5. Teachers encourage children to share knowledge with peers. | C5. Teachers affirm mana and promote reciprocal learning (ako). | Shift to culturally sustaining peer learning and mana affirmation. |

| B6. Teachers intentionally teach The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) competencies through play. | C6. Teachers responsively weave NZC competencies into play. | Stronger alignment with meaningful, relational, mana-enhancing practice. |

| B9. Teachers support resilience when mistakes occur. | C9. Teachers affirm mistakes as relational learning opportunities. | Explicit cultural framing and relational resilience practices. |

| New indicators (2024) | ||

|---|---|---|

| New indicator | Domain | Purpose/rationale |

| A1. Teacher acknowledges and articulates their own cultural background and its influence on practice. | Part A | Requires teachers to acknowledge the influence of their culture, worldview, and lived experience on their daily practice. |

| B6. Teacher uses culturally relevant artefacts in ways that honour tikanga and local hapū/iwi values. | Part B | Embeds tikanga and mātauranga Māori in daily teaching practice and defines play resources from cultural artefacts. |

| E1. Teacher demonstrates little interest in pronouncing children’s names correctly. | Part E | Identifies counter-productive practice undermining identity and belonging. |

| E5. Teacher treats pūrākau and Māori knowledge as decorative or secondary. | Part E | Addresses marginalisation of Māori knowledge systems. |

Note: These examples are illustrative only and do not represent the full tool. They highlight how the research outcomes informed revisions to strengthen cultural responsiveness, clarify teacher behaviours, and identify counter-productive practices that undermine play pedagogy.

Tamariki/student perspectives

Tamariki perspectives were gathered through structured, researcher-designed interviews conducted at both the beginning and conclusion of the study. All 131 tamariki who consented to participate on the day of the interviews, and whose whānau provided consent, participated in the semistructured interviews. It was agreed that, given the age of tamariki, the interview was best conducted in person with someone with whom they had a relationship. As a result, they were interviewed by either their own classroom teacher, or by the team leader. The classroom teacher/team leader followed the semistructured interview framework, but made slight adjustments to their pace, tone, and style dependent on the engagement of tamariki. Interviews were conducted in English. Where tamariki did not have strong language (either due to being non-verbal, ESOL, or as emerging communicators), teachers conducting the interviews adjusted their interview style to maintain a supportive and curious tone throughout the interview process. These interviews provided insight into how students experienced PBL and its impact on their sense of belonging, engagement, and cultural identity.

Whānau perspectives

Whānau were invited to participate in pre- and post-project surveys, which were designed to understand their perceptions of PBL and its role in CSP. These surveys helped to capture whānau expectations, experiences, and observations of how their children engaged in learning through play.

Kaiako/teacher perspectives

Surveys adapted from the school’s previous use of Rongohia te Hau (Berryman et al., 2015), a culturally sustaining practice evaluation tool, were used to gather kaiako perspectives. These adaptations involved tailoring existing culturally sustaining practice measures to include specific questions related to PBL and its intersection with CSP. The adapted surveys retained their focus on the alignment between teaching practices and culturally sustaining principles while expanding to assess engagement with play-based approaches. Additionally, semistructured interviews were conducted with kaiako at the conclusion of the project to gain deeper insights into their experiences, challenges, and reflections on the implementation of culturally sustaining play pedagogies and the professional development they participated in during the project.

Teacher support practices

Wānanga as data collection and support

Wānanga were used not only as a method of data collection but also as a teacher support mechanism, creating spaces for reflection, discussion, and co-construction of culturally sustaining play practices. These wānanga sessions allowed for the iterative refinement of the framework and ensured that teachers felt supported in embedding CSP into their practice.

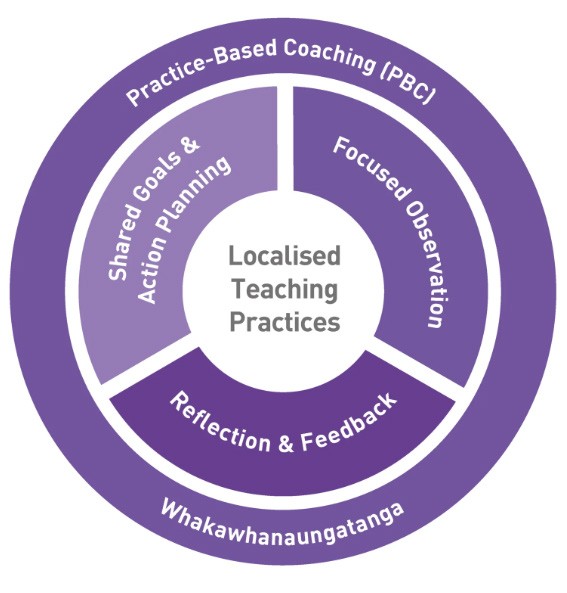

Practice-based coaching (PBC)

A contextualised form of PBC (McLaughlin et al., 2024; Snyder et al., 2022) was used to provide structured and ongoing professional development support for teachers. PBC involves conducting a strengths and needs assessment, focused observations, reflection and feedback, and goal setting cycles to support teacher growth. Figure 2 illustrates the PBC Aotearoa model. At the centre are localised teaching practices, supported through an iterative cycle of focused observation, reflection and feedback, and shared goal setting. The model is grounded in the value of whakawhanaungatanga, emphasising the importance of relational trust and culturally sustaining engagement in professional learning.

Note: Reproduced with permission from McLaughlin and Clarke (2023).

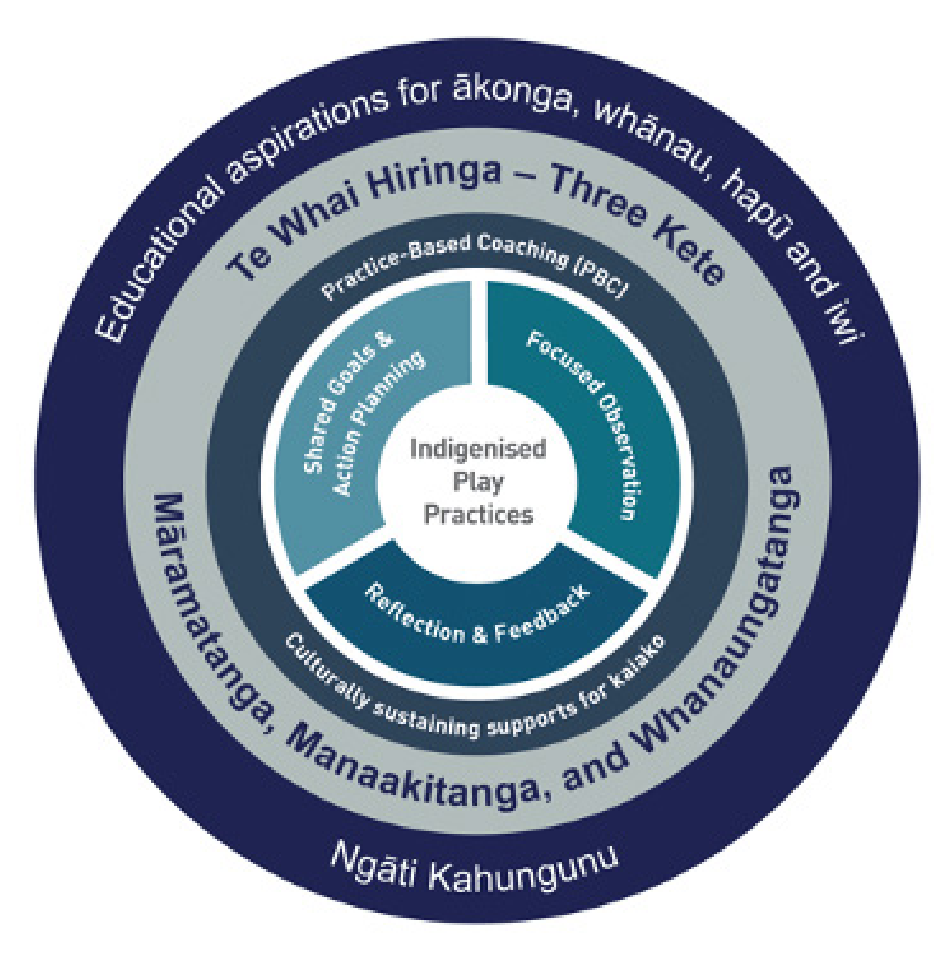

In this project, PBC was adapted to align with the values and context of Te Whai Hiringa. The adaptation emphasised the integration of school values within coaching conversations, ensuring professional learning was culturally and relationally grounded. The resulting model is illustrated in Figure 3.

Note: Reproduced with permission from Aiono et al. (2024).

Coaching data were collected in the form of coaching logs, measuring the length of time of each coaching session, adherence to the fidelity of the coaching approach, and the frequency of identified coaching strategies used per session. Teacher interview data included reflections on the usefulness of the coaching professional development support.

Coaching fidelity and goal setting

To ensure the integrity of the PBC process, coaching fidelity was monitored throughout the project. Teachers participated in 10 coaching sessions, consisting of an initial planning session, eight implementation sessions, and a final reflection session. One teacher completed nine sessions due to a health-related absence.

In terms of observation fidelity, Session 1 recorded full implementation of all coaching practice indicators (100%). Across Sessions 2–8, an average of 5.25 out of seven coaching practice indicators were observed, equating to 75% fidelity. Observation times were consistent across sessions, averaging 30 minutes.

Debrief sessions followed each observation and were also assessed for fidelity. In Session 1, debrief meetings averaged 31 minutes, with 12 out of 13 indicators implemented (92.3%). In Sessions 2–9, debriefs averaged 32 minutes, with 13 out of 15 indicators implemented on average (86% fidelity). The duration of debriefs ranged from 20 to 60 minutes, reflecting the flexible, responsive nature of the coaching process.

Goal setting formed a key component of the coaching cycle, with all teachers establishing their initial practice goal in Session 1. By Session 2, each teacher had achieved their first goal and developed a new one, demonstrating early responsiveness to the coaching process. Throughout the remainder of the project, goal-setting patterns varied, with some teachers revisiting or refining their goals more frequently than others. Notably, Sessions 4 and 7 saw the highest number of new goals set, indicating periods of deeper reflection or pedagogical shift. By the end of the project, all but one teacher had set a goal to continue developing their practice beyond the formal coaching structure. Across the 10-session series, teachers set an average of six goals each, reflecting a sustained and iterative engagement with their professional growth.

Practice implementation checklists (PICs)

In addition to the P-BLOT, this research initially utilised PICs (version 1.0) (Aiono & McLaughlin, 2018) as supplementary tools to facilitate teacher self-reflection and guide coaching conversations. The PICs provided kaiako with practical, accessible descriptions of effective play-based practices, directly aligned with P-BLOT indicators but articulated in “teacher-speak” for ease of use.

Initially, the checklists supported teachers’ reflective practice, enabling them to identify strengths and areas for growth independently. Following focused classroom observations using the P-BLOT, teachers then used the PICs in coaching sessions to engage in dialogue, set goals, and track progress.

Contextualisation was critical to ensuring cultural alignment. Like the P-BLOT review process, the PICs were revised in consultation with Ngāti Kahungunu Kauwaka to integrate te ao Māori concepts alongside each indicator, reinforcing connections between pedagogy, local iwi values, and mātauranga Māori. All items were presented in both te reo Māori and English to provide dual-layered understanding for kaiako.

To illustrate how P-BLOT indicators were translated into accessible, practice-focused items, Table 3 presents examples of alignment between selected indicators and their corresponding PIC checklist items.

| P-BLOT indicator | PIC item |

|---|---|

| Part A, Indicator 2: Teachers identify and respond to the diverse cultural elements of the classroom and community, including engaging with families using te reo and tikanga Māori. | Checklist 1, Item 2: I identify the diverse elements of my classroom and community, and the most effective way to engage with families using te reo and tikanga. |

| Part C, Indicator 7: Teachers support specific skill and knowledge development in the context of play by intentionally teaching knowledge and/or skills needed by the student to advance or extend learning in their play. | Checklist 3, Item 5: Intentionally teach knowledge and/or skills needed by the students to advance or extend learning in play. |

Note: Examples illustrate how indicators from the P-BLOT were translated into accessible, practicefocused items in the PICs. These are provided as illustrative samples only; the full PICs are included in Appendix A.

This ensured the tool functioned consistently across observation, self-reflection, and coaching contexts, while remaining accessible for daily teacher practice. Additional examples of alignment are provided in Appendix A, where the full set of contextualised PICs is included. These examples demonstrate how the PICs operationalised the intent of the P-BLOT, making culturally sustaining practice both observable and actionable for kaiako.

Refinement of P-BLOT and PICs through coaching and Kauwaka consultation

As the revised P-BLOT and PIC were embedded into the coaching process during pou Whakatīnana (Tuarua), refinement of both tools was iteratively informed through consultation with Kauwaka, who gifted te ao Māori concepts to strengthen the intent of each practice indicator. Teacher relationships and interactions were reframed within Māori relational values, while the PICs were revised to provide bilingual guidance (te reo Māori and English) for everyday practice. The coaching model was also adapted to embed school values in each goal, include a Cultural considerations section for tikanga-aligned approaches, and provide a review process for kaiako to seek cultural guidance. This approach enabled continuous feedback and development, ensuring that both Western and Indigenous knowledge systems were honoured within the evolving framework.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies aligned with the research questions and respective data collection tools.

P-BLOT

Observation data collected through the P-BLOT were quantitatively analysed using descriptive statistics to summarise the frequency and quality of observed classroom practices. Changes in these observed practices were captured through comparative analysis of pre- and post-implementation scores, highlighting shifts in the frequency and quality of culturally sustaining and play-based practices. Findings are presented visually through bar graphs to succinctly illustrate changes over the project duration.

Tamariki/student interviews

Tamariki interview responses were analysed qualitatively through a thematic coding process. The data were transcribed, reviewed, and coded to identify patterns in language, perception, and understanding across the pre- and post-project phases. This approach enabled the research team to trace shifts in tamariki views on play, learning, and cultural connection. Thematic categories such as emotional wellbeing, collaborative learning, cultural expression, and metacognitive awareness emerged, providing a nuanced picture of how tamariki experienced and interpreted PBL within the context of a CSP.

Whānau perspectives

Whānau survey responses were quantitatively analysed to identify trends and changes in perceptions over time. Pre- and post-survey responses were summarised using graphical representations and comparative statistics, capturing shifts in whānau expectations, observations, and attitudes towards culturally sustaining play pedagogy.

Kaiako/teacher perspectives

Teacher survey data, based on the adapted Rongohia te Hau surveys, were analysed using descriptive statistics to measure changes in teacher engagement with culturally sustaining and play-based practices. Semistructured teacher interview responses were qualitatively analysed through thematic analysis, highlighting key themes of professional growth, perceived challenges, successes, and reflective insights on pedagogical implementation.

Wānanga data

Data from wānanga served a dual purpose: firstly, as qualitative data informing the iterative design-based research process, and secondly, as a means of directing adaptations throughout each pou (phase) of the project. Wānanga discussions and reflections were thematically analysed to identify critical insights and adjustments needed to the pedagogical framework, ensuring alignment with project goals and responsiveness to identified needs and strengths.

PBC

Quantitative data from coaching logs were analysed to assess the fidelity of PBC implementation, tracking the frequency, duration, and consistency of coaching sessions and strategies. Qualitative reflections gathered through teacher interviews were analysed thematically to evaluate teachers’ perceptions of coaching impacts on their practices, identifying the effectiveness and applicability of coaching supports provided. This combined approach enabled an understanding of the influence coaching had on teaching practices and identified areas for future coaching support.

Key findings

Research question 1: Perspectives and experiences of tamariki, whānau, kaiako, and iwi regarding play

Tamariki

Before the project began, many tamariki were uncertain about whether play was a form of learning. Some even denied that learning could happen through play. However, by the end of the project, tamariki explicitly recognised play as an important part of their learning. They demonstrated a deeper understanding of the role of play in developing academic and social skills. Word cloud analysis showed an increased reference to learning areas such as maths, reading, and problem solving, reinforcing this shift.

A closer comparison of tamariki interviews pre- and post-project provides deeper insight into this transformation.

In response to the question, “How often do you get to play in your classroom?”, students initially described play as something that happened mostly during breaks or in limited pockets of classroom time. Their descriptions were surface-level and often disconnected from learning. Post-project, students gave significantly more detailed and varied examples of classroom play. They talked about making bases, building shops, cooking in the kitchen, making number cakes, or crafting pirate treasure. They also linked play with autonomy, indicating they were able to “choose after reading” or “play most of the day”. This shift suggests not just a change in opportunity, but in how play was perceived as a valid and valued part of their classroom experience.

When asked about learning through play, the contrast was even more pronounced. Pre-project responses were often vague or uncertain, with many saying “I don’t know” or suggesting that learning and play were separate. Post-project, tamariki offered richer and more reflective responses, identifying social, creative, and academic learning: “I’m learning how to be a builder”, “We are counting with beads”, “When I make a mistake I restart and then I learn”, and “Playing and learning are the same.” These responses show emerging metacognitive awareness and increasing ability to identify learning in action.

When asked whether play was important for learning, pre-project responses were mixed. Some said yes, but many said no or were unsure. In contrast, post-project responses reflected more conviction, especially in relation to social and emotional learning: “You get to be with your friends”, “It helps you learn to share”, “You get smarter.” While a small number of students still viewed play and learning as separate, there was clear growth in both the number and quality of responses affirming the learning potential of play.

Overall, these findings suggest a notable shift in how tamariki understood, valued, and articulated the relationship between play and learning. The change was not only in language but also in confidence, clarity, and conceptual understanding. Students developed a more integrated view of learning that included emotional regulation, collaboration, creativity, and academic exploration, core elements of culturally sustaining play pedagogy.

Kaiako

P-BLOT data indicated significant shifts in teaching practices, particularly in teacher behaviour and cultural connection. Teachers showed greater confidence in incorporating PBL, aligning their approaches more effectively with CSP. Many reported feeling more equipped to use play as a teaching tool, rather than as an isolated activity. One teacher reflected, “I now see how important play and language are for these kids”, highlighting the shift in pedagogical mindset. Another shared, “Students turn their forts into marae with ‘no shoes’ signs”, demonstrating the integration of cultural identity into play environments.

However, teacher perspectives also revealed ongoing tensions. While some felt increasingly confident: “I’ve learnt a lot of reo and tikanga since I started, and I feel more comfortable now”, others remained hesitant: “I don’t want to do it wrong and dishonour the culture.”

Teachers also described learning alongside tamariki:

I’ve learned alongside the kids. A lot of our children don’t have much at home, so Pūrākau and the way we’ve been able to teach that … it’s been the best learning for both of us. (Teacher 4)

Play would’ve just been stuff out and packed away. Now, I see the role I play in drawing out their thinking and identity. (Teacher 5)

Whānau

Whānau showed strong initial support for PBL, with 90.6% agreeing that play is key for developing values and life skills. Nearly all respondents (96.8%) recognised that play was essential for oral language development, and 93.7% acknowledged that using play in the classroom did not take away from literacy and numeracy instruction. Some whānau initially preferred a more formal teaching approach but, over time, most recognised the benefits of play as a learning tool.

However, a key limitation was the very low response rate to the post-project whānau survey. Despite extending the response window into Term 4, engagement remained limited. Two factors likely contributed: the timing (end-of-year commitments and holidays); and the heavy workloads of both whānau and kaiako, which reduced opportunities for active follow-up (e.g., phone calls or kanohi-te-kanohi contact). As a result, post-project insights into whānau perspectives remain incomplete. This meant that, while strong baseline insights were gathered, the project was unable to determine whether shifts in whānau perspectives occurred over the duration of implementation.

Future iterations of the research would benefit from deeper engagement strategies to support longitudinal whānau feedback, ensuring the full arc of change is captured and understood from both school and home perspectives.

Research question 2: How play practices align with manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, and māramatanga

Tamariki/student perspectives

By the end of the project, tamariki made stronger connections between play and the school’s core values. They described play as a way to express kindness (manaakitanga), build friendships (whanaungatanga), and support others in their learning. Their responses reflected more than surface-level engagement, revealing an increased awareness of cooperative learning, social responsibility, and the emotional experience of being part of a learning community.

Post-project interviews showed tamariki describing how they helped others solve problems during play, looked out for their friends, and worked collaboratively on imaginative projects. Examples included, “I help my friend build if he gets stuck” and “We share ideas and take turns.” These narratives were not only aligned with whanaungatanga but also demonstrated the embedding of relational practices through everyday classroom experiences.

Tamariki also articulated moments of empathy and collective care: “We play doctors, and I fix people who are sick” and “If someone is sad, I play with them.” Such responses indicated that manaakitanga was not only a school value—they were living it through play. The growth in this type of reflection suggested a deepening capacity for understanding their roles as learners and community members. In addition, many students noted that their learning involved supporting others, signalling growing awareness of the reciprocal nature of play-based, culturally sustaining pedagogies.

Kaiako perspectives

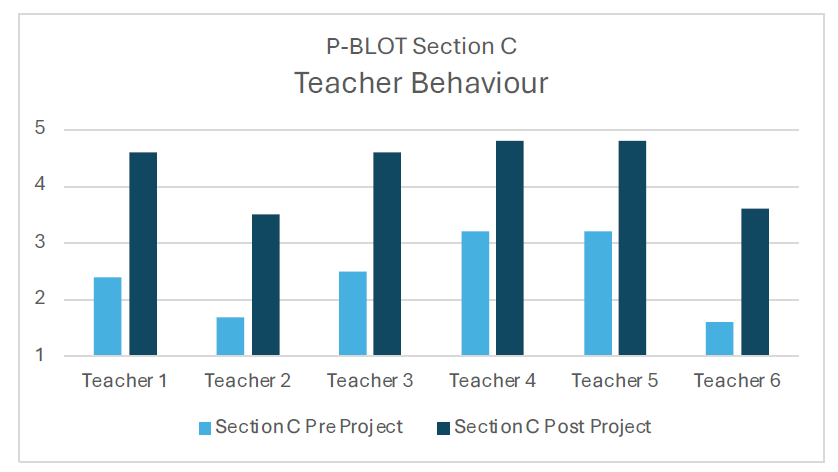

Section A (Cultural connection) was a new addition to the P-BLOT, introduced following wānanga and consultation with the project team during Pou Whakatīnana/Tuatahi. As such, pre-project data were not collected for this section, limiting direct comparisons of practice change over time. However, post-project observations indicated that all teachers demonstrated areas of strength across each of the five indicators within this new section. Section C (Teacher behaviour) did show measurable improvements pre- and post-project, with significant shifts observed in teachers’ practices, reflecting enhanced alignment between play-based pedagogy and culturally sustaining approaches. One teacher explained, “Coaching made me realise the connections between play and cultural relevance.”

Teachers also noted how cultural narratives influenced construction play:

They were building trenches and talking about musket wars. It wasn’t just ‘guns’, it became a conversation about Māori history, about whānau knowledge. That depth wouldn’t have come through a worksheet. (Teacher 3)

This improvement is visually represented in Figure 4 demonstrating clear growth from pre- to post-project phases.

Note: Scores reflect the evidence of teaching through play practices identified in Section C of the P-BLOT. In the original 2018 Research edition, these indicators were located in Section B; in the updated 2024 Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro version, they are presented as Section C. Section C contains 15 indicators, each scored on a 1–5 scale (1 = little evidence observed; 5 = strong evidence observed).

Whānau perspectives

Pre-project, the majority of whānau (93.7%) agreed that play helps reinforce manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, and māramatanga. They also valued play for fostering tuakana–teina relationships, where older or more experienced learners support younger or newer learners. These findings suggest that play was viewed as a meaningful way to uphold cultural values in the school community.

In summary

Across tamariki, kaiako, and whānau perspectives, play was consistently recognised as a vehicle for enacting the school’s core values. Tamariki emphasised everyday experiences of care and co-operation, kaiako described deliberate pedagogical shifts that connected play to cultural narratives and deeper learning, and whānau highlighted intergenerational practices such as tuakana–teina. Together, these perspectives illustrate a shared commitment to embedding values through play, while reflecting the unique lens of each group.

Research question 3: Professional learning and development needs for teachers

Support needs and growth areas

Teachers required ongoing coaching, mentoring, and wānanga to successfully implement culturally sustaining play pedagogies. The adapted P-BLOT tool and coaching cycles provided valuable professional learning support, enabling teachers to refine their practices over time. Coaching was described as transformative: “Coaching made me realise the connections between play and cultural relevance” (Teacher 3).

One teacher elaborated:

I don’t think I could have done it alone … now I see how the language we use can facilitate their thinking, not take it away. (Teacher 5)

P-BLOT results

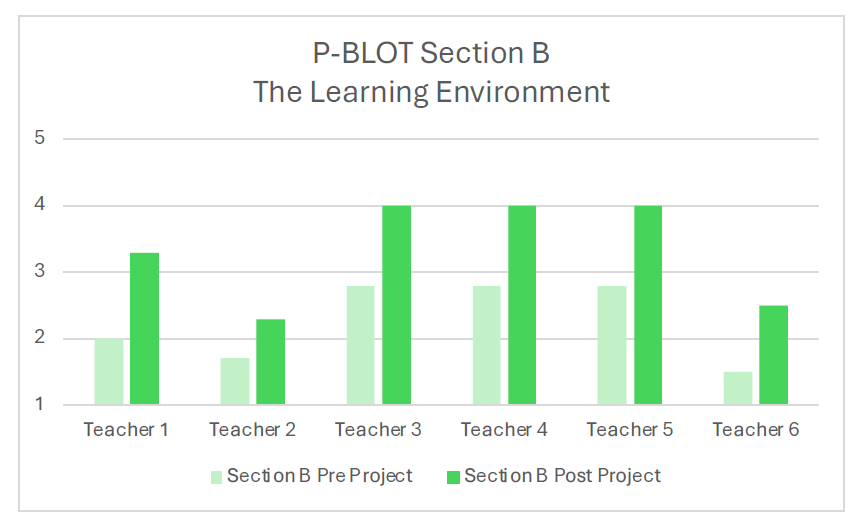

The greatest improvements were seen in the learning environment (P-BLOT Section B) and teacher behaviour (P-BLOT Section C) post-project implementation. These findings suggest that professional development was effective in enhancing teacher confidence and competence in integrating play-based, culturally sustaining responsive approaches. These observed shifts in practice align closely with the structural and indicator-level revisions to the P-BLOT (see Tables 1 and 2), and with the alignment of these indicators to practice-implementation checklists (see Table 3), which together emphasise culturally sustaining teacher behaviours and learning environments.

Figure 5 illustrates individual teacher growth in Section B (The learning environment) of the P-BLOT from pre- to post-project phases. All teachers demonstrated improvement to varying degrees, with the most significant shifts observed for Teachers 3, 4, and 5, who each showed substantial increases in their scores. Notably, Teachers 1, 2, and 6 also displayed positive but more moderate gains. Collectively, these data highlight the overall effectiveness of the professional development and coaching interventions in enhancing the quality of the learning environments to better support culturally sustaining play pedagogies.

Note: Scores reflect the evidence of teaching through play practices identified in Section B of the P-BLOT. In the original 2018 Research edition, these indicators were located in Section A; in the updated 2024 Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro version, they are presented as Section B. Section B contains eight indicators, each scored on a 1–5 scale (1 = little evidence observed; 5 = strong evidence observed).

Challenges faced

Despite positive progress, teachers highlighted key challenges that impacted their ability to fully implement culturally sustaining play pedagogies.

Access to culturally sustaining resources

Teachers frequently expressed the need for more resources that authentically reflect tamariki identities, cultural narratives, and lived experiences. While they were committed to embedding mātauranga Māori into play, the lack of suitable materials made it difficult to do so meaningfully. One teacher reflected: “We still need more culturally relevant resources … we try to buy things that reflect our mokopuna, but we need so much more”. (Teacher 1)

Another shared how they were often left improvising: “… I ended up sourcing things for free. It wasn’t just about cost—it was about not being able to find what really reflected our learners”. (Teacher 5)</p?

Balancing curriculum demands with play pedagogy

Teachers described the constant tension between engaging in child-led, culturally connected play and meeting the formal expectations of the curriculum. This often left them feeling stretched and conflicted. One teacher shared that “It’s hard to think about how to plan culturally relevant play while meeting curriculum demands.” Another indicated that “I still feel like I’m missing the resources and deeper knowledge I need.”

Time was a particular constraint, with teachers navigating structured literacy blocks, mandated assessments, and large class sizes. One teacher explained:

Sometimes you don’t have long enough with any one child to go deeper … You’re putting out fires or being pulled somewhere else. (Teacher 4)

Others noted the emotional impact of wanting to honour tamariki identities but feeling illequipped or unsupported. Teacher 5 shared that “I don’t want to step on people’s toes or teach the wrong thing and dishonour the culture. I try my best, but sometimes I’m unsure what that actually looks like.”

These insights point to the need for system-level support including time allocation, culturally aligned resources, and deeper professional learning, if culturally sustaining play pedagogies are to flourish.

Research question 4: Impact of culturally sustaining play pedagogies on tamariki/student cultural identity and belonging

Strengthened cultural identity

Building on the themes of kindness and co-operation noted in Research question 2, tamariki also described how play supported leadership, agency, and cultural growth. Some spoke about teaching others or taking turns, highlighting the reciprocal nature of ako (teaching and learning together) and their developing sense of responsibility within the group. Others linked play directly to cultural values such as manaakitanga and māramatanga, describing how it fostered growth, care, and relational integrity, hallmarks of culturally sustaining pedagogy.

Some tamariki described the ways play connected with leadership and collective wellbeing: “I learn to teach others how to build” and “We take turns … I teach my friends.” These quotes speak to a developing sense of agency and the reciprocal nature of ako (teaching and learning together), suggesting a strengthening of identity within the classroom context.

Cultural values such as manaakitanga and māramatanga were also evident in comments like “Playing helps your brain” and “We listen to the teacher, we need to be sharing more, keep being kind.” Tamariki began to associate their actions during play with ideas of growth, care, and relational integrity, hallmarks of culturally sustaining pedagogy.

While not all tamariki explicitly connected play with learning, many were beginning to identify how their play experiences helped them think about others and express themselves. As one said, “I like playing in the afternoon … when I’m learning and playing at the same time.” This layered response reflects the growing integration between cognitive, emotional, and cultural learning that was nurtured through play.

These findings align with teacher and P-BLOT data, confirming that culturally sustaining play pedagogies enhanced tamariki identity, belonging, and confidence. Play became more than a classroom activity, it became a context in which tamariki saw themselves as valued, capable, and connected members of their learning community. The strengthening of tamariki identity and belonging reflected here is consistent with the revised indicators that emphasise relational pedagogy, reciprocal learning, and cultural identity (see Table 2).

Kaiako practice

Teacher interview data supported these findings, highlighting how play helped kaiako deepen their understanding of students’ cultural identities and affirm tamariki as learners. Several kaiako described observing tamariki express whakapapa through play: “They made a wharenui and talked about their nanny and how she used to tell stories at the marae” (Teacher 3). Teachers also reflected on how play provided an entry point into conversations about tikanga and cultural values, with one noting, “It opened the door to talk about manaakitanga in a way that was natural and real” (Teacher 2).

Teachers also acknowledged their own growth in cultural confidence, with Teacher 4 stating, “I didn’t grow up with this knowledge, but now I can support it, name it, and celebrate it when I see it in the kids’ play.” Another observed, “It’s not about doing culture on a Friday, it’s embedded in how we learn together” (Teacher 1).

This shift is reinforced by the alignment of observation and practice tools (Table 3), that supported kaiako to see how culturally sustaining pedagogy could be enacted in daily routines.

These reflections, in combination with P-BLOT data, demonstrate that culturally sustaining play pedagogies supported kaiako to foster inclusive environments where tamariki identity and belonging were actively nurtured. Teachers grew in their ability to notice and respond to the ways tamariki brought their culture into the learning space, affirming identity through relational, responsive teaching.

Taken together, the perspectives of tamariki, kaiako, and whānau show a consistent pattern of culturally sustaining play pedagogies strengthening identity, belonging, and connection, though with some variation in emphasis. Tamariki highlighted the immediate, lived experience of play as a space for friendship, kindness, and shared learning, while also beginning to articulate how play linked to cultural values and leadership. Kaiako perspectives aligned with these shifts but placed greater emphasis on their own professional growth, noting how play enabled them to recognise and affirm tamariki whakapapa, tikanga, and cultural identities within everyday practice. Whānau, meanwhile, reinforced the importance of play as a vehicle for language, tikanga, and cultural expression, though the limited post-project data restrict insight into changes over time. Together, these perspectives suggest that play, when intentionally framed through a CSP, fosters a learning environment where tamariki feel secure, valued, and connected, and where teachers and whānau increasingly see identity and culture as integral to learning rather than supplementary.

Overall impact

The findings of this project suggest that culturally sustaining play pedagogies positively influenced both tamariki and kaiako across multiple dimensions of learning, identity, and relational practice. For tamariki, play became a vehicle through which they not only explored but also affirmed who they are, culturally, socially, and emotionally. Their growing ability to articulate how play supports learning, their use of te reo Māori, and their enactment of cultural roles and values demonstrate a shift toward deeper identity development and a stronger sense of belonging within the classroom environment.

For kaiako, the project fostered professional growth in culturally sustainable and relational pedagogy. Teachers not only embedded more intentional cultural practices into their play environments but also expressed increased confidence in supporting tamariki identity through everyday interactions. They saw themselves as co-learners alongside their students, navigating how to honour tikanga authentically and sustain cultural narratives within play.

Together, the data highlight that culturally sustaining play pedagogies are not simply an approach to learning, they are a way of being in the classroom that affirms mana, builds whanaungatanga, and cultivates inclusive, identity-rich environments. As one teacher shared, “There’s a real pride now in who they are and where they come from and play helped unlock that.”

Project outcomes: Development of the Indigenous play framework

Origins and initial adaptations

Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro | The Play-based Learning Observation Tool Version 2.0 (Aiono et al., 2024) emerged as an evolution of the original P-BLOT (Aiono & McLaughlin, 2018). During the first wānanga review, indicators were systematically examined against the school’s core values, leading to revisions that emphasised tikanga, cultural responsiveness, and the appropriate use of taonga and other artefacts. This process highlighted where indicators already aligned with cultural values and where adaptations were required, reinforcing the importance of critically testing the tool against Māori worldviews. The resulting framework is both culturally sustaining and pedagogically robust, ensuring that tamariki experiences of play are responsive to their identities, languages, and cultural contexts. These developments are summarised in the structural shifts (Table 1), illustrated through selected indicator examples (Table 2), and operationalised for teacher practice through the aligned checklists (Table 3).

Expanding the framework: Cultural connection and counterproductive practices

A key outcome of the wānanga process was the recognition that CSP required a more explicit focus on cultural connections and practices within the P-BLOT. As a result, a fifth section, Cultural connection and practices, was created, incorporating five indicators informed by research in culturally sustaining and relational pedagogy (Bishop & Berryman, 2006). These indicators focused on teacher knowledge and practice of te ao Māori, including whakawhanaungatanga, storytelling, and iwi-specific knowledge transmission.

Additionally, insights from Rongohia Te Hau research (Berryman et al., 2023) informed revisions to the Counterproductive practices section. Several indicators were added to reflect teaching behaviours that are counter to culturally sustaining practice, such as the tokenistic use of te reo Māori, failure to acknowledge whakapapa, and rigid adherence to Western knowledge systems over Indigenous ways of knowing.

Supplementary resource: PICs

In addition to the revised P-BLOT, the framework incorporates the PICs as a supplementary resource to support teacher reflection and professional growth. The PICs were revised in alignment with the updated P-BLOT indicators and contextualised with te ao Māori concepts, providing kaiako with a practical self-reflection tool. Designed in accessible “teacher-speak”, the PICs help educators to recognise strengths, identify next steps, and embed culturally sustaining play practices in everyday classroom contexts. The full set of contextualised PICs is included in the appendix to guide ongoing implementation for educators interested in learning more about these practices.

Challenges and considerations for the future

One of the most significant challenges that emerged from the findings of this project was the diversity of mātauranga hapū and the misconception that Māori knowledge is homogeneous. While Te Whai Hiringa stands on Ngāti Kahungunu whenua, its tamariki and whānau come from a broad range of hapū and Pacific affiliations, making it essential that kaiako present local mātauranga accurately while also respecting diverse cultural perspectives.

To address this, teachers identified a need for centralised iwi- and hapū-specific resources that could be used as accurate reference materials in the classroom. This was highlighted as a key implication of the project and a recommendation for future research and professional development.

The final version of the P-BLOT and revised PIC resources will remain as working documents for teachers, guiding ongoing coaching and development into 2025 and beyond. A final wānanga will be held to formally share the revised framework and celebrate its publication, with student artwork from Te Whai Hiringa adorning the cover as a symbol of collective ownership.

Discussion and implications

The findings from this project provide insights into the role of culturally sustaining play pedagogies in primary education. These insights have important implications for future teaching practice, professional learning, school leadership, and educational research. Key areas for future action and inquiry are summarised below.

Strengthening culturally sustaining play pedagogy in schools

While this research confirmed that play can effectively support cognitive, social, and cultural development, challenges remain in balancing structured curriculum expectations with play-based approaches. Future practice could develop clearer curriculum connections between play and formal learning outcomes to bridge perceived gaps between play and achievement in literacy and numeracy. In addition, teachers could be provided with exemplars and strategies to better integrate play into structured learning without compromising autonomy, creativity, and cultural sustainability. Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro| The Play-based Learning Observation Tool Version 2.0 provides concrete guidance for teachers in how to enact these shifts, as reflected in the examples of revised and new indicators (Table 2).

Building on these challenges, schools and education providers could co-develop culturally sustaining materials in partnership with iwi, hapū, and whānau. Future research could explore how play materials shape student identity and engagement, particularly in Māori-medium and bilingual learning settings.

The project highlighted how play can reinforce school values (manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, and māramatanga). Moving forward, schools could develop schoolwide frameworks that explicitly integrate local iwi aspirations, tikanga, and cultural practices into PBL. Kaiako and whānau could be encouraged to co-design these frameworks to ensure that culturally sustaining play practices are meaningful, localised, and not tokenistic.

Enhancing teacher professional learning and development

The adapted P-BLOT tool and coaching process played a crucial role in supporting teachers’ pedagogical shifts. Future professional development should be structured to account for workload realities, ensuring coaching and mentoring can be sustained alongside daily teaching demands.

Despite positive shifts, teachers varied in their confidence when implementing culturally sustaining play pedagogies. Future professional learning should support kaiako to deepen their knowledge of Indigenous play pedagogies (e.g., ira tākaro frameworks) and provide more direct access to iwi knowledge holders so that teachers can authentically integrate te reo me ōna tikanga into play.

PBC was central to ensuring that the shifts in pedagogy were not only trialled but embedded over time. As an evidence-based professional development approach, PBC created structured opportunities for observation, reflection, feedback, and goal setting, while maintaining a relational and culturally grounded focus. This iterative cycle enabled kaiako to translate the aspirations of the framework into daily practice, strengthening their confidence and competence in culturally sustaining play pedagogy. By embedding coaching within the project, professional learning moved beyond one-off workshops to an ongoing process of growth, increasing the likelihood that practice changes would endure.

School leadership and systemic change

The research reinforced that play is often misunderstood as “not real learning”, both by some teachers and whānau. To drive systemic change, school leaders must advocate for PBL at governance and policy levels. Further research could measure and make available the long-term academic and social impacts of PBL, particularly in relation to student achievement, engagement, and wellbeing.

A lack of resources and structured time for play remains a challenge in mainstream schooling. Policy makers and educational leaders should recognise the critical role of play in culturally sustaining education and allocate funding for play-based professional learning. In addition, policy models that legitimise play within structured curriculum frameworks could be explored, ensuring equity for diverse learners.

Limitations

The study was conducted within a single school context (Te Whai Hiringa), which limits broader generalisability to other educational settings, particularly those without strong iwi partnerships or a pre-existing PBL culture. Moreover, design-based research involves close collaboration between researchers and practitioners. While this is a strength in terms of real-world applicability, it also means that findings may be contextually specific (i.e., developed for Te Whai Hiringa, with strong iwi involvement). Researcher facilitation played a key role, which means we cannot fully isolate whether shifts in teacher practice would persist without ongoing support. The framework was continuously refined, meaning the intervention itself was evolving, making it harder to determine which specific elements contributed most to observed changes.

Furthermore, the study primarily captured short-term shifts in practice and perception. While findings showed clear improvements in CSP and PBL confidence, the long-term impact on student outcomes (e.g., achievement, identity development, engagement) was not measured. A longitudinal approach would be necessary to understand sustained teacher practice change and whether tamariki cultural identity and learning outcomes continue to evolve over time.

Despite efforts to collect post-project whānau survey data, only three responses were received, making it difficult to assess how whānau perspectives may have evolved over time. This means the project has limited insight into whānau reflections on the long-term impact of culturally sustaining play pedagogies on their children.

The qualitative nature of CSP makes it difficult to create measures for its effectiveness. The P-BLOT tool was adapted to include cultural connection indicators, but these still rely on researcher interpretation and teacher self-assessment. Cultural shifts in belonging, identity, and language use develop over time, and the study period may not have been long enough to fully capture these deep transformations. Potential research impacts were also impacted by time constraints on teachers’ engagement in reflective wānanga and coaching cycles. This is a common challenge in design-based research, where research must fit within the realities of teacher workloads. Despite the limitations and cautions noted, the study provides insights and inspiration for the type of work that can support effective change in schools.

Implications for future research

This study captured short-term shifts in teacher practice and student perceptions. Longer-term research is needed to explore how culturally sustaining play pedagogies impact student achievement and engagement over multiple years. Additionally, the relationship between play and student identity formation, particularly for Māori learners in mainstream schools, requires further investigation.

The research highlighted the importance of iwi and whānau in shaping culturally sustaining play practices. Future research could explore how iwi-led educational models can extend play pedagogies in both mainstream and Māori-medium education. Further investigation is also required into historical and contemporary Māori play traditions and their applications in modern schooling.

Conclusion

This research project offered an opportunity to explore how culturally sustaining play pedagogies might support tamariki and kaiako in deepening their engagement with learning, identity, and culture. The findings suggest that, when play is intentionally positioned within a framework that honours mātauranga Māori, relational values, and responsive teaching, it can provide a meaningful platform for tamariki to explore who they are and how they learn.

Tamariki perspectives indicated a growing awareness of play as both a learning tool and a space for cultural expression. Their reflections, though varied, point to an increased sense of belonging, connection, and pride. Many began to articulate the ways in which their play helped them learn about themselves, others, and the world around them.

For kaiako, the project appears to have contributed to shifts in practice and confidence. Teachers described learning alongside their students, with play offering a relational entry point to cultural knowledge and pedagogical sustainability. While some kaiako still expressed uncertainty, most demonstrated a greater willingness to engage with te ao Māori and to reflect on their role in supporting tamariki identity within the learning environment.

This research adds to the growing understanding of how culturally sustaining practices can be meaningfully integrated into everyday teaching. It highlights the potential of play—not as a separate activity, but as a pedagogical approach woven into the values, language, and lived experiences of the learners and their communities.

As the whakataukī at the heart of this project reminds us, Ko te tākaro te kauwaka e pakari ake ai te tangata: play may serve as a vessel through which children grow strong. While the journey is ongoing, these findings suggest that such an approach has the potential to support culturally grounded learning environments where all tamariki can see themselves, feel valued, and flourish.

References

Aiono, S. M. (2020). An investigation of two models of professional development to support effective teaching through play practices in the primary classroom. [Doctoral thesis, Massey University]. Massey Research Online. https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/16350

Aiono, S., & McLaughlin, T. (2018). Play-based Learning Observation Tool Research Version 1.0 (P-BLOT 1.0): Manual and supplemental resources. Unpublished instrument. Massey University.

Aiono, S., McLaughlin, T., & Riley, T. (2019). While they play, what should I do? Strengthening learning through play and intentional teaching. He Kupu, 6(2), 59–68.

Aiono, S., Waitoa Tuala-Fata, T., & McLaughlin, T. (2024). Ara Mātai Ako ā-Tākaro| The Play-based Learning Observation Tool Version 2.0 (P-BLOT 2.0): Manual and supplemental resources. Taonga Auaha.

Anderson, T. & Shuttock, J. (2012). Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher, 41(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11428813

Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

Berryman, M., Egan, M., Haydon-Howard, J., & Lamont, R. (2023). Rongohia te Hau: Better understanding the theories underpinning cultural relationships for responsive pedagogy. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0096

Berryman, M., SooHoo, S., & Nevin, A. (2015). Relational and responsive inclusion: Contexts for becoming and belonging. Peter Lang.

Bishop, R. (1996). Collaborative research stories: Whakawhanaungatanga. Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R. & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture speaks: Cultural relationships and classroom learning. Huia Publishers.

Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), 141–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2

Brown, H., & Brown, L. (2022). Ira tākaro: Strengthening cultural identity through play. In He Rautaki Whakaako: Indigenous pedagogies for tamariki Māori. Author.

Davis, K. (2015). Children’s agency and voice in play-based classrooms. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland].

Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032001005

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hedges, H. (2018). The role of content knowledge in early years teaching and learning: A case study in play-based curriculum. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(2), 61–70.

Isaac-Sharland, T. (2020). Te Tōpuni Tauwhāinga: Ngāti Kahungunu Education Strategy. Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated.

Kallen, H. M. (1924). Culture and democracy in the United States. Boni & Liveright.

Lacey, T. (2021). Māra hūpara: Reviving ancestral play spaces for holistic wellbeing. Healthy Families Rotorua.

McLaughlin, T., & Clarke, L. (2023). Practice-based coaching Aotearoa (PBC Aotearoa) Manual, protocols, and logs: Leadership coaching programme. Unpublished Guide, Massey University.

McLaughlin, T., Clarke, L. R., Gifkins, V., & Carvalho, L. (2024). ECE leadership coaching: A valuable investment. [Final report of the Leadership Coaching Programme]. Massey University. https://eyrl.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/LCP-Final-Report_website.pdf

Milne, A. (2016). Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream schools. Peter Lang.

Milne, A. (2020). Colouring in the white spaces: The warrior-researchers of Kia Aroha College. Curriculum Perspectives, 40(1), 87–91.

Milne, B. A. (2013). Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream schools. [Doctoral thesis, University of Waikato.]

Ministry of Education. (2020). Ka hikitia—Ka hāpaitia: The Māori education strategy. Author. https:// www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia/

Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

Penetito, W. (2010). What’s Māori about Māori education? Victoria University Press.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Norton.

Smith, G. H. (1992). Taha Māori: Pākehā capture and Māori resistance. In M. King (Ed.), Te ao hurihuri: Aspects of Māoritanga (pp. 183–190). Reed Publishing.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books. Snyder, P. A., Hemmeter, M. L., & Fox, L. (2015). Supporting implementation of evidence-based practices through practice-based coaching. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35(3), 133–143.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press.

The appendix for this online version of the report had been removed. However, you can access it here