Executive summary

Overview of the research intent and approach

This is the third report in the TLRI Project Plus series of analyses. It presents the findings from an exploratory investigation of the impacts of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI). The investigation sought evidence of the extent to which TLRI is meeting its three core aims:

- to build a cumulative body of knowledge that links teaching to learning

- to enhance links between research and practice across the early childhood, school, and tertiary sectors

- to grow research capability and capacity in the areas of teaching and learning.

At the start of the project we anticipated that impacts in these three different areas could well interact with each other, such that the whole would be more than the sum of the parts. We shaped a two-phase exploratory approach that allowed for this possibility. A stratified random sample of 12 completed TLRI projects was drawn, aiming to be representative of projects from the three sectors (early childhood, school, tertiary) and of shorter and longer running projects. The leaders of the sampled projects were invited to take part. Those who agreed provided names and email contact addresses for members of their teams. Eventually a sample of nine projects was achieved. This sample comprised two early childhood projects, four school sector projects, two tertiary projects, and one cross-sector (school to tertiary) project.

In the first phase everyone from the nine projects who agreed to take part was invited to complete a short online survey. Forty-five individuals did so—an overall response rate of 62 percent. The response rate from practitioners was lower than that from researchers, in part because they were harder to reach. Five projects each yielded at least four responses from people with different perspectives (project leaders, researchers, practitioners). These projects continued into the second phase of the research.

In the second phase we interviewed three or four participants from each of the five projects. Most interviews were face to face, but some were conducted by telephone. There was one early childhood project, one focused on secondary–tertiary transitions, one set in secondary schools, and two with a focus on initial teacher education in the context of school-based learning.

| “Our initial expectation was that the main impacts would be knowledge-based. … What actually emerged was a person-based conceptualisation of impact.” |

A breakthrough insight

Our initial expectation was that the main impacts would be knowledge-based. For example, a new insight about a specific type of teaching challenge might emerge, and any new practices described might be taken up beyond the project, assuming that the findings were effectively disseminated. What actually emerged was a person-based conceptualisation of impact. One of the very first things most interviewees said was along the lines of, “I have totally changed how I am as a teacher. I could not now go back to the way I did things before”.

The details of this personal realisation varied with each person’s role and context.

However, in every case they could describe direct links between the events of their TLRI

involvement, as they had experienced them, and a profound change to their practice. It was this initial change that rippled outwards in waves of further impacts, and these became ever more diverse and diffuse due to the unique context of each person’s story or stories (the same sort of change often took different directions in subsequent impacts). As a result, much of the report is organised around highly contextual impact narratives, which emerged from these rich conversations with participants in the second phase.

The critical importance of partnerships

To qualify for funding consideration TLRI proposals must show convincing evidence that a robust partnership between researchers and practitioners will underpin the envisaged research. The development of stronger researcher−practitioner relatioships and links was seen as an area of strong or some impact by 93 percent of survey respondents. Everyone we interviewed in the second phase described this requirement for the formation of strong partnerships as central to the success and impact of TLRI overall.

Researcher−practitioner partnerships play an important role in the dynamics of how projects unfold and in what is learnt as they do so. Collaborations afford rich opportunities to “make the familiar strange”. Researchers can hold up a critical mirror to allow practitioners to reflect on what they do and why they do it. Tacitly held knowledge might surface in this way. At the same time, practitioners can open up critical insights into the complexities and practicalities of teaching and learning that might otherwise go unremarked by the researchers. These dynamics open up space to look at familiar practices afresh, while providing practitioners with new strategies for continuing to use and consolidate emergent practices.

Here is an indicative example of the partnership dynamic at work. (There are a number of other examples within the body of the report.) One beginning researcher talked at length about the growth in his ethical awareness as a consequence of working through the ethical procedures of his university in the early stages of a project. Teachers often talk informally about students during the course of a working day. Greater ethical awareness had given this newly fledged researcher pause to notice and think about the wider implications of doing so. This was a powerful experience that is likely to stay with him and influence his future interactions with both teachers and students, when teaching as well as when researching.

How impacts ripple outwards from person-centred change

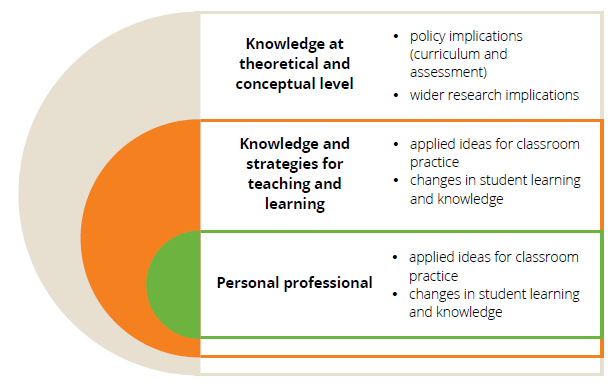

All those we interviewed nominated these personal changes as the biggest impact of being involved in TLRI, and in some cases these changes had far-reaching consequences. In many different ways, impacts that emerged during projects had the potential to spread like ripples in a pond, reaching further and further and into other contexts as participants used their new insights and skills in ways they might not have anticipated at the project outset. Starting from the personal, the range of important impacts within the overall education system might be characterised as follows.

- New insights directly affect teaching and learning. Many experiences recounted by participants illustrated the powerful impact of changing awareness. This could relate to matters as diverse as context and culture; students’ needs and challenges;

- teachers’ needs and challenges; self-efficacy for teaching; ethical considerations; and/or the epistemology of a discipline area.

- New practices directly affect teaching and learning. New insights and changes in practice are often linked. However, practice changes do need to be highlighted separately because they can either precede insights or follow them. The concrete support for making robust and defensible changes in practice was an important feature of all the TLRI partnerships we explored.

- Existing leadership roles provide direct avenues for dissemination. Many participants already held a leadership role in their place of employment, and in some cases in regional or national groups. These roles provided an avenue for distributed sharing of new insights and practices, with the aim of encouraging and supporting others to make similar changes.

- New leadership/career opportunities open up. Involvement in a TLRI can open new horizons, with an associated expansion of opportunities for sharing impacts via a wider sphere of influence. Examples in just these five projects included moving from teaching to a role in teacher education, moving into a new faculty leadership role, and taking on new responsibilities in a teacher education programme.

Types of impacts on teaching and learning

Almost all the survey respondents perceived that TLRI projects had made an impact via new or changed teaching and learning practices and via benefits for learners, which we can infer were a result of the teaching and learning changes. Three-quarters or more of respondents said these impacts were strong. The clear pattern here is the strongest impacts occurring when putting new knowledge to work in actual teaching and learning contexts.

There is a lot going on during any episode of teaching and learning, and teachers cannot focus on everything. It was clear that projects supported teachers to direct their attention in productive ways, helping them notice things that were worth trying to change and showing them ways to do so. In different ways, every project afforded opportunities for participants to take a step back and think carefully about the learning needs of those with whom they worked (children in some cases, young adults or adults in others). This was an important source of new insights, typically followed by changes in practice.

The potential strengths of learners sometimes took participants by surprise. Situated and contextually rich research projects can open up spaces for learners to confound expectations that might otherwise limit them. It was the young people themselves who put pressure on teachers to give them more difficult writing challenges in the transition project, for example. When learners are aware that their teachers are also learning, the nature of the interchanges between them shifts in powerful ways. The act of learning per se can then become a focus for learning conversations. The following are examples of evidence of this type of impact.

- Some school students in a project with a focus on pedagogy gained the confidence to ‘push pause’ and ask their teacher to explain again when an aspect of their learning was not clear.

- Secondary history students in one teacher’s class were actively involved in learning with him how to carry out research with iwi, not just learning about the products of such research.

- Student voice became an important routine aspect of teacher−student interactions in the NCEA[1]project.

- Mentor teachers brought to light their own tacit knowledge about effective teaching and learning as they supported beginning teachers to notice and strengthen aspects of their emergent practice.

- Young children were supported and encouraged to make active use of their diverse language strengths in the early childhood project.

Some projects invested in developing or adapting tools that became central to the research. Applying the tools within the research and beyond was a significant contributor to learning about research. One team invested hugely in developing new tools to make judgements about student-teachers’ progress towards their registration as fully fledged competent teachers. The work involved in developing and using these tools had an impact on participants’ research abilities, on their teaching practice, and on wider teaching and research communities. At least two participants based their postgraduate study on the use of one or more of these tools.

Striving for impact from knowledge outputs

The sections above introduce the proposition that person-centred impacts are an important feature of TLRI endeavours. Balancing this discussion, it is also important to note the many and varied knowledge outputs and their impacts. We did not endeavour to capture every output from every person in each project. The projects were so varied— and some included so many team members, both directly and indirectly—that this would have been a large undertaking. Instead, we developed examples that illustrate several noteworthy features of the overall impact of the knowledge outputs. These included:

- the considerable attention and effort given to face-to-face dissemination to relevant practitioner audiences, which was a common feature across all five projects

- the inclusive efforts of project leaders—members of the wider team were often involved in these face-to-face knowledge-sharing activities, and, like the bullet point immediately above, this type of commitment is a logical consequence of the strong partnerships built during the projects, and the esteem for each other’s expertise that developed between researchers and practitioners

- the practical support provided to any team members who wanted or needed to write more formal types of knowledge outputs (reports, papers, book chapters, a whole book in one case)

- the dissemination of knowledge via new tools, processes or resources—in one way or another this was a feature of all five projects and was an important avenue for sharing new knowledge well beyond the originating project teams.

There was clear evidence of the reach of knowledge outputs that connect directly to teacher education programmes. The two projects directly embedded in teacher education contexts illustrate the knowledge-sharing potential when insights spread beyond the originating institution to reach others who also support beginning teachers.

Powerful synergies can be created when TLRI knowledge outputs interact with other areas of educational research and activity. Formal outputs directly related to any one project might only be the beginning of an expanding and morphing knowledge journey. In our sample this was most vividly illustrated by the intersection between a specific type of pedagogy being researched by one team and theoretical ideas of culturally responsive pedagogy. The potential for synergies was also evident when new ideas were carried across into other policy work; for example, when they interacted with curriculum or assessment activities of teacher-leaders.

These impacts continue to reverberate well beyond the lives of their projects. For example, insights generated by the secondary−tertiary transition project, which ended several years ago, are currently being disseminated in well-subscribed workshops for tertiary educators.

1. Introduction to the research

This report presents the findings from an investigation of the diverse impacts of the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI). The overarching concern of this work was to seek evidence of the extent to which TLRI has been successful in meeting its foundational aims, and to identify areas for further strengthening or change in order to maximise its effectiveness in doing so. This is the third report in the TLRI Project Plus series of analyses.

The aims of TLRI

The TLRI initiative began in 2003. It was set up with three overarching aims:

- to build a cumulative body of knowledge that links teaching to learning

- to enhance the links between educational research and teaching practices—and researchers and teachers—across early childhood, school and tertiary sectors

- to grow research capability and capacity in the areas of teaching and learning.

The intention was that these aims would be addressed via carefully constructed research projects, awarded in small numbers each year after a highly competitive bidding round. By the time the research reported here began in early 2016, 125 projects had been funded.

Earlier investigations of TLRI in relation to its aims

The TLRI Advisory Board and the NZCER TLRI co-ordination team have previously used various mechanisms to consider how well TLRI is addressing its aims, and how project teams can be supported to contribute to these aims. Reviews of completed projects in each sector (i.e. early childhood, school, tertiary) were undertaken from 2010 to 2012, with a primary focus on the first of TLRI’s aims. Each review considered the question “What contribution have early years/schooling/tertiary sector TLRI projects made to building knowledge about teaching and learning in these sectors?” (Nuthall, 2010; Zepke & Leach, 2011; Hill & Cowie, 2012). Each review was followed by a sector-based symposium that resulted in specific recommendations for guiding and shaping the ongoing programme of research.

The TLRI Advisory Board and the NZCER TLRI co-ordination team have also commissioned the Project Plus series of ‘meta’ projects. This series is adding value to the overall TLRI programme by synthesising findings across multiple projects, as follows.

- The first Project Plus report focused on two highly successful projects in the area of statistics education. It investigated how and why they had been so evidently successful in shifting the teaching and learning of statistics in New Zealand schools (Hipkins, 2014).

- The second Project Plus report synthesised over 20 literacy-focused projects to explore how ‘literacy’ has been conceived and investigated, and to look for patterns in recommendations made as a result of this varied range of projects (McDowall, 2015).

The current investigation has broadened the scope of the previous evaluative work (i.e. the sector reviews) by considering all three aims of the TLRI in relation to each other. This is the third Project Plus investigation.

| “We anticipated that impacts in these three areas could well interact, such that the whole would be more than the sum of the parts.” |

Scoping the nature of potential impacts

For the purposes of this investigation, the TLRI aims were initially expanded into three broad impact descriptors.

- Building a cumulative body of knowledge linking teaching and learning: Traditional impact indicators in this area include citations, publications and conference papers. Such ‘outputs’, at least during and in the immediate aftermath of the project, should be recorded on the project page on the TLRI website[2]. The impact project sought to get beneath the surface of these metrics to ask what sorts of links have been built between teaching and learning, and how these new insights have informed changes to practice.

- Impacts on practice: Teachers and researchers have their own perceptions of changes in practice. These perceptions were a major focus of the impact project, with a particular focus on sustainable changes. The nature and strength of links developed between researchers and practitioners was also a focus for the research.

- Impacts in the area of growing educational research capability: The project has investigated the extent to which those involved in TLRI projects perceived that they (or those they had mentored and/or partnered) had developed new research skills and knowledge, and if so, how these new capabilities have affected their ongoing work (either teaching or research).

At the start of the project we anticipated that impacts in these three different areas could well interact with each other, such that the whole would be more than the sum of the parts. Weaving together the three potential areas of impact outlined above, evidence of impact was sought by asking about matters such as:

- how learners had benefited

- the development and use of any teaching and learning tools

- ways in which whānau and wider communities had benefited

- any contribution made to policy development or implementation

- how contributions to new knowledge had been shared and disseminated (as well as the traditional outputs listed above, others with a wider reach were included, such as popular press, social media, blogs)

- the impact on career pathways for researchers in the project team

- the impact on career pathways for practitioners in the project team (either as teacher-researchers or as practitioners)

- establishing and/or strengthening cross-disciplinary and cross-institutional relationships.

We began with a quantitative phase, surveying participants from the sampled projects to gain their perceptions of impacts in all these areas (see section 3).

Lists of publications and presentations for any one project could be considered indirect evidence of impact. In the qualitative phase of the project we gathered details of as many outputs as we could (see section 7) but did not pursue this metric further. Doing so would have required us to analyse citation indices of journals, collect numbers of attendees at conferences, and so on. Even then we would have needed to make assumptions about the uptake of the ideas, with no evidence and no manageable way to gather that evidence. We decided early on that we would not follow this sort of metrics-based approach. Instead, our plan was to get ‘up close and personal’ with a range of participants in a small sample of projects, talking directly to those involved about the immediate and longer-term impacts on their work of TLRI involvement.

In the school sector, achievement data are often gathered as evidence of the immediate impact of an initiative. This is another potential source of quantitative data we chose not to pursue. Individual school-based projects have often reported such data, and we saw little potential for adding value by trying to replicate or extend such analyses.

As the following sections will show, these decisions paid dividends. Much of the report is organised around highly contextual impact narratives, which emerged from our rich conversations with participants.

2. Overview of the research process

The research questions

The research questions that guided this work are:

- What knowledge outputs have been generated, both within and beyond the project? Does the team have evidence that insights from the project have been picked up and used by others?

- How have project activities and findings impacted on teaching and learning within and beyond the project? What evidence do the researchers cite to support their impact claims?

- In what ways have each respondent’s research skills and knowledge changed as a consequence of taking part in the project?

- What perceptions does each participant have of the impact of their project within the New Zealand education system as a whole?

Creating a sample from completed projects

A stratified random sample of 12 completed TLRI projects was drawn, aiming to be representative of projects from the three sectors (early childhood, school, tertiary) and of shorter and longer running projects. The sample included options for substitutions should these be needed. Other variables considered were: length of time since project completion; and type of project (Type 2 projects are considered to be more exploratory than Type 1 projects). Any projects with which the research team had been directly involved[3] were withdrawn before the sampling was undertaken.

The leaders of the sampled projects were invited to take part. Those who agreed provided names and email contact addresses for members of their teams. Where a project leader declined to participate, the invitation was then sent to the leader of the substitution project from the sample. Invitations were followed up wherever possible, and eventually a sample of nine projects was achieved. This took several months.

The achieved sample for the survey phase

The achieved sample for the first stage of the research comprised two early childhood projects, four school sector projects, two tertiary projects, and one cross-sector (school to tertiary) project. Once the full list of contacts had been compiled (as provided by the project leaders who agreed to take part), all potential participants were invited to contribute to the short online survey that constituted the first stage of the project. Names and email addresses given to us by the project leaders provided a potential sample of 73 individuals. The composition of this sample (based on email addresses provided), and the numbers who actually responded, are shown in Table 1.

| Group | Number invited | Number who responded |

Response rate % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal investigators (project leaders) | 10 (one project had co-leaders) |

8 | 80 |

| Research team members | 26 | 25 | 96 |

| Practitioner team members | 37 | 12 | 32 |

The achieved sample was 45 individuals—an overall response rate of 62 percent. The table shows clearly that the response rate from practitioners was much lower than that from researchers. Some early childhood teachers proved hard to reach because project leaders were only able to provide a common email address for their place of employment. It was easier to establish direct contact with school and tertiary teachers and leaders because they had individual email addresses. However, in some cases one or more members of a project team had changed their place of employment. If project leaders had lost track of where team members went, we could not contact them. If project leaders knew where they had gone, we endeavoured to track their new contact details, but several of our messages bounced back.

Creating the sub-sample for the interview phase

At the end of the survey, respondents could indicate if they would be willing to take part in the second, interview, phase of the work. The intention was to select up to four respondents for each project, and to select this group to represent a diversity of perspectives on the project as a whole (based on their survey responses). In the event, just five projects from the original sample yielded a sufficient diversity of volunteers for the follow-up interview phase.

We subsequently interviewed three, or in most cases four, participants from each of these five projects. Where possible, interviews were face to face, but some were conducted by telephone. There was one early childhood project, one focused on secondary− tertiary transitions, one set in secondary schools, and two with a focus on initial teacher education in the context of school-based learning.

Analysis and synthesis

Early in the interview phase it became clear to us that we needed to rethink our initial conceptualisation of the nature of the impacts we might find. Our survey questions were shaped with the three broad aims of TLRI in mind (section 1). Our interview questions were based on response patterns in the survey. It now became clear that we had assumed the main impacts would be knowledge-based; for example, a new insight about how to address a specific type of teaching challenge might emerge as an output of a research project. Then the new practice described might be taken up beyond the project, assuming that it was effectively disseminated.

What actually emerged, right from the very first interviews, was a person-based conceptualisation of impact. One of the very first things most participants said was along the lines of: “I have totally changed how I am as a teacher. I could not now go back to the way I did things before”. The details of this personal epiphany varied with each person’s role and context. However, in every case they could describe direct links between the events of their TLRI involvement, as they had experienced them, and a profound change to their practice. It was this initial change that rippled outwards in waves of further impacts, and these became ever more diverse and diffuse given the unique context of each person’s story or stories (the same sort of change often took different directions in subsequent impacts).

This insight challenged our initial analysis plan. We were intending to code thematically for changes related to each of the three TLRI aims. Now we could see we needed to devise a new approach. With the person-centred metaphor for impact in mind, we settled on a succinct re-telling of various aspects of the rich change stories we were hearing. We shaped and grouped these stories according to our main impact themes. This allowed us to keep the situated complexity of different types of impacts intact while still addressing our original research questions.

Other writers wrestling with the complex nature of impacts have also focused on “stories of impact”, paying particular attention to how participants tell their stories: what they focus on and why they see these details as important (see, for example, Marsh, Punzalan, Leopold, Butler, & Petrozzi, 2016). We have also taken this approach to our analysis of the qualitative stage of the project.

3. Initial survey findings

The survey was short. We aimed to keep response times as close as possible to 10–15 minutes so that respondents were able to give their impressions of impacts without being overburdened. It was envisaged that more probing reflections would be gained in the follow-up qualitative stage.

We collated the frequency data from the survey, but the sample size (n = 45) precluded some of the additional analysis we had initially envisaged. We did check for differences between patterns of responses from researchers and practitioners, but, as the following discussion will show, only a few were found, no doubt in part because of the small sample size.

A brief note about terminology is needed at this point. TLRI projects must be partnerships between researchers and practitioners. We therefore differentiate between those whose core role on the project was as ‘researcher’ (usually university-based staff) and those who teach in other settings (e.g. early childhood centres, schools), who we collectively call ‘practitioners’. This distinction between researchers and practitioners avoids confusion, but it should be noted that it is not clear cut. University-based participants in TLRI are usually teachers as well as researchers, and many of those in partner institutions, who are primarily teachers, also took active research roles in their TLRI projects.

| “The clear pattern here is that the strongest impacts occurred when putting new knowledge to work in actual teaching and learning contexts.” |

Impressions of various types of possible impact

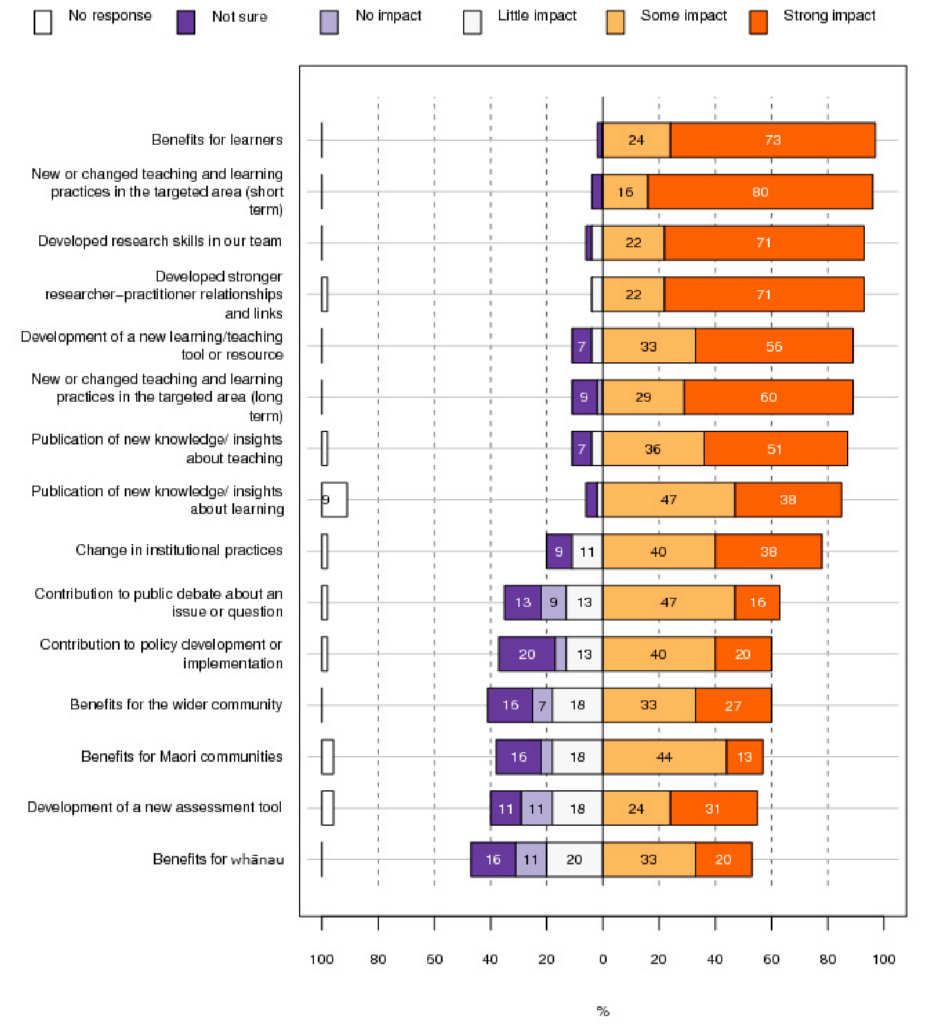

Figure 1 shows responses to a bank of questions that invited overall impressions of various types of impacts from the project to which respondents had contributed. Almost all the respondents perceived that TLRI projects had made an impact via new or changed teaching and learning practices, and via benefits for learners, which we can infer were a result of the teaching and learning changes. Three-quarters or more of respondents said these impacts were strong.

The clear pattern here is that the strongest impacts occurred when putting new knowledge to work in actual teaching and learning contexts. Practitioners who perceived short-term impacts on teaching and learning also perceived that these were sustained longer term. Some researchers shifted their position, and a small number (four) were unsure if impacts continued over the longer term. The interview responses (see next section) showed how ‘sustainability’ can become something of a shape-shifter when newly acquired practices morph and travel to different settings. People further away from those making such changes could not be expected to be as aware of this widening circle of longer-term impacts.

Seventy-one percent of respondents perceived strong impacts on research skills within their team, and the same percentage perceived a strong impact from developing stronger relationships and links between researchers and practitioners. As might be anticipated, the researchers themselves were significantly more likely to say the impact on the development of their research skills was strong: 81 percent said this, and the remainder of the researchers said there was some impact. By comparison, the teachers’ views were distributed across the response categories, but half of them did also perceive strong impacts on research skills. The impact narratives later in the report illustrate the varied ways in which these impacts played out.

Most respondents said that a new teaching or learning resource had made at least some impact, and 56 percent said this impact was strong. TLRI projects are not funded to produce resources per se. However, teams might develop specific types of resources to support changes in practice they wish to research. Alternatively, they might do so as a form of dissemination of the project’s findings.

The development of new assessment tools rated lower for impact in comparison to teaching and learning resources. A third (31 percent) of respondents perceived a strong impact in this area. Again, TLRI projects are not funded to develop new assessment tools, but some project teams find they need to do this in order to address their research questions. Both previous Project Plus reports have described examples of this need. For example, researchers investigating ways to foster critical literacies have found they needed to develop new assessment tools because existing literacy assessments did not focus specifically on critical literacy capabilities (McDowall, 2015).

The publication of new knowledge at theoretical/conceptual levels was also seen as a source of impact but did not rate as highly as the more practical aspects outlined above. As Figure 1 shows, 51 percent of respondents perceived strong impacts from new knowledge about teaching and 38 percent perceived strong impacts from new knowledge about learning. However, later sections of the report will show that the distinction between knowledge of teaching and knowledge of learning is perhaps not as clear-cut as implied here.

The group of items ranked somewhat lower for perceptions of strong impact might be collectively thought of as ‘outreach’ impacts; i.e. beyond the immediate target area of a project. (But note that over half of all respondents did perceive some impact or a strong impact—the relative ranking is what is lower for this group.) A quarter of respondents (27 percent) perceived strong benefits for the wider community as a result of the research in which they were involved. The first Project Plus inquiry revealed that influencing policy makers can make an important contribution to the impact of research (Hipkins, 2014). For example, as a consequence of their research, a team might identify a need to refocus an aspect of curriculum or high-stakes assessments. If they are strategic in the way they go about convincing policy makers, the envisaged change might be successfully achieved. However, just 20 percent of respondents reported a strong impact in this area. Sixteen percent perceived that their project had made a strong impact by contributing to public debate about an educational issue.

Both early childhood and school-level education emphasise the principle of establishing and maintaining partnerships between schools and their immediate communities. Both sectors are also strongly committed, in principle, to honouring the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. A small proportion of respondents perceived that there had been strong benefits for whānau (20 percent) or for Māori communities (13 percent). Sixteen percent of respondents were unsure if there had been benefits in any of these three areas (wider community, Māori community, whānau). Almost all of these ‘unsure’ responses were made by researchers, not practitioners. This makes sense, as researchers are more likely than practitioners to be one step removed from educational interactions with the wider community or Māori community and whānau. Later sections of the report will provide a more nuanced discussion of the challenges implied here.

Perceptions of personal gains in research capabilities

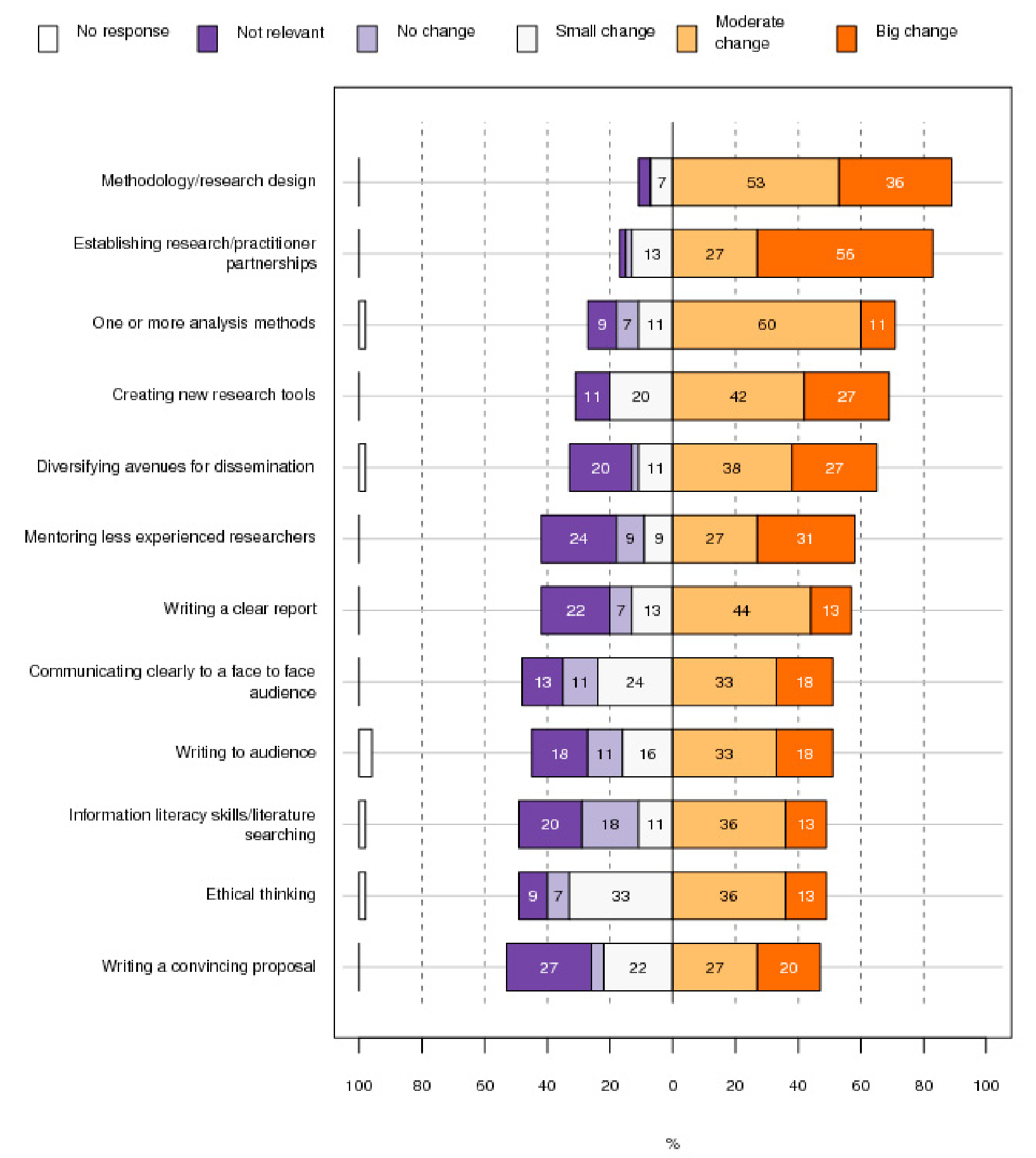

Research is a complex activity, with many potential areas where capabilities might become stronger. With this complexity in mind, the second bank of Likert-scaled survey items endeavoured to build a snapshot of specific areas that participants believed had been strengthened by taking part in TLRI research. Figure 2 shows the overall pattern of responses. For this second bank of survey items there was no discernible difference between patterns of responses from teachers and researchers: both groups appear to have grown from these encounters.

| “The highest frequency of perceptions of ‘big change’ was in establishing researcher-practitioner partnerships.” |

When perceptions of big and moderate changes are added together, most participants (89 percent) said they had increased their personal capabilities in methodology/research design. However, the area with the highest frequency of perceptions of ‘big change’ was in establishing researcher−practitioner partnerships (56 percent big change, 83 percent big or moderate change). Many respondents also perceived personal changes in mentoring less-experienced researchers (31 percent big change, 58 percent big or moderate change).[4] Notice that these two items, which describe partnership aspects of TLRI, are the only ones where perceptions of big changes constitute a larger proportion of responses than perceptions of moderate changes. When these changes happened it seems likely they were powerful experiences for many respondents. Again, the impact stories in later sections will illustrate how and why this was so.

Methods of data analysis constituted an area of big or moderate change for 71 percent of respondents. As already noted, when a research question is seen to be breaking new ground, it can be necessary to create new research tools that are fit for purpose, and this was an area of big or moderate change for 69 percent of respondents. Forty-nine percent of respondents said they had made big or moderate changes in their own ethical thinking, and the same percentage said they had made big or moderate changes in literature searching and information skills.

Sixty-five percent of respondents said they had made big or moderate changes in diversifying avenues for dissemination. Somewhat fewer respondents said they had developed their capabilities in writing a clear research report (57 percent had made big or moderate changes). Just over half the respondents (51 percent) had made big or moderate changes in communicating clearly with a face-to-face audience. A similar number had made big or moderate changes in writing with a specific audience in mind (51 percent). The bottom-ranking item was writing a convincing proposal (47 percent big or moderate changes). The interviews showed that project leaders prefer to keep tight control of this early stage of a project, for a range of reasons.

Participation patterns for dissemination activities

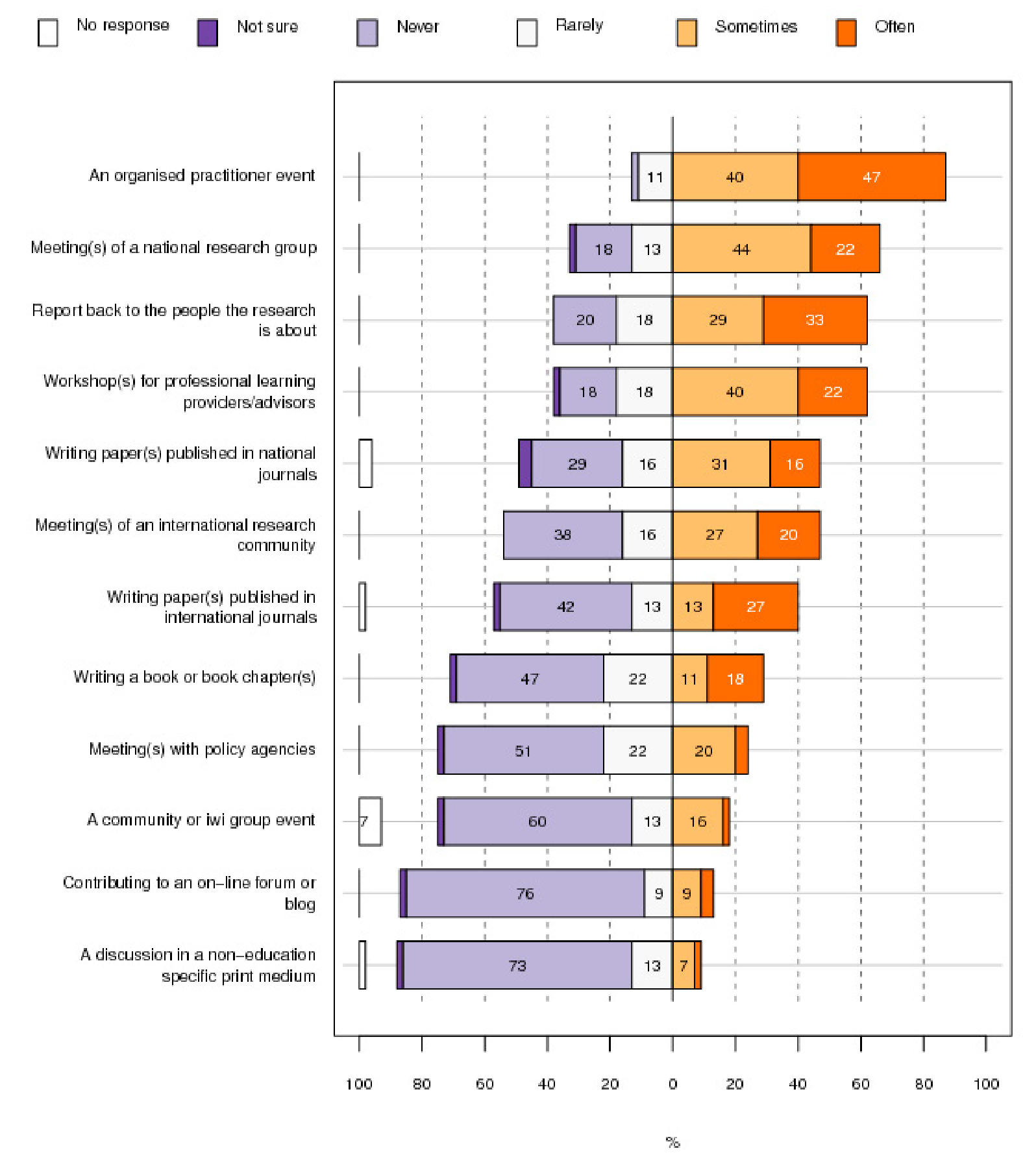

Figure 3 displays responses to a bank of items that asked about respondents’ participation in a range of potential avenues of dissemination and discussion of their project’s findings. The most frequent activity was participation in an organised event for practitioners (87 percent had done so sometimes or often). These conversations included people whose teaching and learning had been a focus for the research (62 percent had reported back to their research participants sometimes or often). A similar precentage had taken part sometimes or often in conferences or workshops that conveyed findings to other interested practitioners.

In contrast to the banks of items already reported, more of the items in this bank showed differences between the responses of the researchers and the practitioners. Perhaps not surprisingly, researchers were more likely to have discussed the project in an international research community. Just 47 percent of respondents had done so sometimes or often. Eight of the 12 practitioners said they had never done so, as did nine of the 33 researchers. The pattern was similar for talking to a national research group, although this appeared to be a more accessible activity overall (66 percent of respondents had done so sometimes or often).

Researchers were also more likely to have taken part in formal written dissemination, both in national journals (47 percent had done so sometimes or often) and in international journals (40 percent had done so sometimes or often). Writing book chapters was less common again (29 percent had done so sometimes or often). Note that the latter item did not show a significant difference between researchers and practitioners, no doubt because many in both groups had never written a book chapter.

Informal written communication is not at all common. The majority (76 percent) had never written a blog about the research, nor had 73 percent ever written a discussion for a noneducation-specific print medium (e.g. a newspaper or magazine). Similarly 60 percent had never spoken about the research at a community or iwi event.

Most participants had never, or only rarely, met with policy agencies. Ten of the 11 who said they had done so sometimes or often were researchers.

These overall responses patterns are brought to life in the next three sections as insights from the interview phase of the project are introduced into the impact picture being developed.

4. Setting the stage for subsequent impacts

This is the first of four sections that discuss insights generated by the qualitative phase of the project. As the previous section showed, the development of stronger researcher− practitioner relationships and links was seen as an area of strong or some impact by 93 percent of survey respondents (Figure 1). Establishing such partnerships was perceived to be an area of big or moderate personal change for 83 percent of survey respondents (Figure 2). This section adds to that snapshot by discussing how the very act of establishing partnerships required for TLRI projects can be a critical stage on which subsequent impacts will build.

| “the very act of establishing partnerships required for TLRI projects can be a critical stage on which subsequent impacts will build.” |

How genuine partnerships lay the ground for impacts to come

Everyone we interviewed described the requirement for the formation of strong partnerships as central to the success and impact of TLRI overall. The first of the report’s impact narratives[5] illustrates how and why a genuine partnership, formed right at the outset of a project, greatly strengthens the likelihood that subsequent impacts on both knowledge generation and practice will be well grounded in the practical realities of the complex work of teaching and learning.

| Right from the beginning of one project, schools were involved in discussing what they might do. The university set the practitioners up as co-researchers. There were 16 people in the project team altogether, and everyone was seen as both a practitioner and a researcher. The project leader noted that “We tried to make sure the group made the decisions—we wanted them to feel it was their project as well as our project. If you want to set up a TLRI you need to start thinking about partnerships the year before and start talking to your partners. It’s no good signing them up on the dotted line one minute before you hand the proposal in.” A researcher–practitioner similarly said, “We sat around the table from meeting one and developed the project as a team. We had academic staff and school staff working together and that’s been the nature of our work with the university. The germ of the idea came from the university but we had a voice from the very beginning, including in the research methodology and all aspects of the project”. |

The two voices heard in this narrative illustrate how strong partnerships allow the researchers’ questions and ideas to be directly informed and enhanced by the practical insights of practitioners.

The role of the project leader

Once a TLRI project has been successful in gaining funding, the hard work of forging strong partnerships shifts up a gear. There is potential for rich personal professional learning to take place as each team builds a shared understanding of what they are going to do, how they are going to do it, and why they are going to approach the research in the manner agreed.

Project leaders have a critical strategic role in shaping this shared sense of purpose that subsequently drives the impact of the project as a whole. At the proposal writing stage they typically prefer to take full ownership of the intellectual challenges as they try to draw disparate threads together and weave a coherent and cogent whole. They then involve other researchers and practitioners in refining the proposal and, subsequently, in developing and refining the project plan.

Another key role for project leaders is building both the research and practice capabilities of team members in the partnership. One project leader said that during the project “not micro-managing” had been an important aspect of her leadership. Leaving space for others in the team to develop the ground work in areas of their allocated responsibility “allowed unexpected things to happen”. A researcher in another project considered that

it wasn’t by accident that they had a mixed team where they could all learn and grow. It was a good investment by the Faculty and the leadership was clear and focused and encouraging. The project leader kept the ship moving with a clear intention without making too many allowances.

The next section addresses actions, interactions and personal professional learning as projects unfold. The very personal nature of impacts will be apparent in the narratives, but the main analytical focus will be on the different types of teaching and learning impacts that emerge at this stage of the overall research cycle.

5. Impacts on teaching and learning as the research unfolds

This section explores the dynamics of how practical knowledge of and for teaching and learning is built during TLRI projects as they unfold. Once again, researcher−practitioner partnerships can be seen to play an important role, both in the dynamics of how projects unfold and in what is learned as they do so. Participants from all organisations involved learnt from each other, regardless of the nature of the partnership. Even when members of a team already knew each other, the project provided a “deeper level of working together”. One project leader noted that partnerships could be expanded at any stage of a project as new needs emerged. For example, data specialists joined her team at a very late stage of the TLRI and brought a whole new set of knowledge and skills to the overall team: “We all learned from each other”.

This section is organised around themes that illustrate how impacts that emerge during projects have the potential to spread like ripples in a pond, reaching further and further into other contexts as participants used their new insights and skills in ways they might not have anticipated at the project outset. These themes are:

- the power of raising awareness of learners’ needs and strengths as part of a project’s empirical activities

- the ongoing and widening impact of support for ‘noticing’ different things during acts of teaching and learning

- the possibilities for ongoing learning that are afforded by the creation of new tools.

Reflective practice sits at the heart of each theme. In the words of one practitioner, being part of a TLRI project had made him “more genuinely reflective and critical of our own practice [as a school team]—in useful ways”.

| “Impacts that emerge during projects have the potential to spread like ripples in a pond, reaching further and further into other contexts.” |

Raising awareness of learners’ needs and strengths

Collaborations between researchers and practitioners can afford rich opportunities to “make the familiar strange”. Researchers can hold up a critical mirror to allow practitioners to reflect on what they do and why they do it. Tacitly held knowledge might be brought to the surface in this way. At the same time, practitioners can open up critical insights into the complexities and practicalities of teaching and learning that might otherwise go unremarked (and might, for example, make the difference between success and disappointment when trying out a new initiative) (Heckman & Montera, 2009). The following narratives illustrate the impact of new insights about learners’ needs and strengths, generated as a result of partnership interactions.

| From the questionnaire used at the beginning of their early childhood project, the practitioners found out a great deal about parents’ backgrounds and the languages they spoke with their children. Some of the data surprised them and got them thinking about what they needed to know about the children’s experiences and needs. They realised that this wide range of home languages meant children were also likely to be using multiple languages during play. Video clips subsequently confirmed this when they showed children using a different language when acting “being the teacher.” One university researcher commented on the implications for the learning needs of student teachers: “It flagged up that when we think about our early childhood student teachers we realise that we don’t have good materials we can give them.” This insight resulted in the production of new resources to address the challenge of working across multiple languages in early childhood settings.

Two practitioners who were part of the same TLRI project but in very different schools spoke about the impact of being observers while the TLRI project leader and another researcher interviewed students about their learning. Both watched how these experienced researchers responded to what students said and drew out further insights from the students. Both practitioners reflected deeply on the value of those insights and the impact they had subsequently made on their teaching and learning decisions. Both are now more deliberate in the ways they, and other members of their teams, seek “student voice” during learning, not just at the end of a specific unit or course. As one of them explained, “It is a constant thread in the teaching as we go” and gives “real-time evidence” of the impact of planned learning experiences. He noted that other teams in the school have now picked up on these developments. |

Both these narratives highlight the potential for immediate practical impacts once awareness of specific learner strengths and needs has been raised. The act of researching opens up space to look at familiar practices afresh while providing practitioners with new strategies for continuing to use and consolidate emergent practices.

The first of these two narratives also illustrates how the production of new resources can follow as a consequence of what is discovered about learners’ needs and strengths during a TLRI project. Such resources would be counted as traditional knowledge outputs (i.e. a way of putting the project’s findings to work) and are therefore a comparatively visible type of impact. In the second narrative a powerful impetus for change came when secondary teachers had the opportunity to watch at first hand as experienced researchers used their skills to draw out insights about learning needs and strengths during interviews with school students. Subsequent impacts for learners could be said to have been a consequence of the modelling of sound research practices; i.e. a contribution to expected outputs in the area of growing research skills (the second of the TLRI aims).

The next two narratives expand the timeframe by showing how slower-burning insights about learners’ needs and strengths might build over time and continue to reverberate long after a project has finished. Both also draw in the third of the TLRI aims—developing strong partnerships—to show how all three broad aims can interact to produce robust impacts from TLRI projects. These narratives come from two researchers from different universities (and from different TLRI projects). In them the researchers comment on how much better they now understand the learning and support needs of first-year university students. For both, this has been one important consequence of working closely alongside secondary teachers in their respective projects.

| A researcher who teaches the same subject as the secondary teachers in her project continues to work with them when she can, well after the project’s completion. She said the teachers had given her insights related to the nature of the learning incoming students had experienced in their final year at school. On the basis of this knowledge she has changed the structure of her first-year course to provide more choice and challenge of the sort students are likely to have already encountered at school. She saw this as important for retaining their interest in the subject beyond the first year of university and was trying to encourage other teachers of first-year university students in her discipline to do the same. Her project gave another researcher the chance to see at first hand the enormous pressure on teachers to scaffold students’ learning in ways that maximised their chances of success in NCEA assessments. This experience made her acutely aware of the mismatch between the carefully supported secondary teaching and tertiary teachers’ expectations of readiness for fully independent study at university. She now plans for a more closely managed transition at the start of the first year of university study. |

Both these lecturers have drawn on their TLRI experiences to have candid discussions with incoming students about the differences between secondary and tertiary learning environments, and to find out more about the learning experiences and needs students are bringing with them from school. An enhanced awareness of students’ learning needs underpins these changes and emerged as a consequence of the close and trusting relationships forged between secondary and tertiary teachers (i.e. it was a consequence of the partnership requirement of TLRI).

Note also that in these narratives, practice changes were made by the researchers as well as the practitioners. Impacts on practice are not a one-way street.

| “An enhanced awareness of students’ learning needs … emerged as a consequence of the close and trusting relationships forged between secondary and tertiary teachers.” |

Supporting ‘noticing’ during teaching and learning

The third theme in this section has already been foreshadowed in the narratives above. The very act of working together allowed researchers and practitioners to notice things in the teaching and learning context they might not have otherwise been aware of. Some projects also included aspects of noticing as a specific research focus. The next two narratives illustrate how this intention might play out in different learning contexts.

| One TLRI project investigated a pedagogical technique designed to draw studentteachers’ attention to learning challenges as these emerge during learning interactions. The researchers in one participating institution adapted the basic approach to accommodate time constraints that precluded working with individual students one-on-one. Three students planned a teaching sequence (with support), and they then ‘taught’ the whole class. All the student-teachers in the class, along with the researcher (who was their teacher-educator), took part in ‘pause and notice’ conversations.

At the start of the course student-teachers tended to notice really basic things, such as “Can everyone see the board?” However, as time went on they began noticing challenges to developing subject content. Both researchers we interviewed noted that these conversations built deep content knowledge and helped students construct relationships between diverse concepts. One said the process “works brilliantly” and “has changed entirely the way I teach maths”. She noted that this work had moved her beyond recognition of students who had “the X factor” to a firm belief that all student-teachers can get better at their craft. In their course evaluations many of the student-teachers showed their appreciation for “really learning how to teach”. |

| In a project that focused on the provision of feedback during a practicum, one practitioner noted that student-teachers who came into their school were “getting better and better feedback and support and are developing more effective teaching practices”. The new observation and feedback processes that were the focus of the research were seen to make student-teachers very employable. The project leader noted that the benefits for beginning teachers have a flow-on effect to the children: “We know about the summer effect, we don’t want the BT [beginning teacher] effect”. One researcher said, “I’m not being disingenuous—the TLRI has had a big impact on me and others and all the four schools are still involved in the faculty. It grew people and the findings were transferable and practical. It wasn’t some funny little thing that has been written about and been forgotten.” |

Both these projects demonstrated the power of providing support in order to direct beginning teachers’ attention during the learning action in which they have just participated. The research instruments that were collaboratively developed at the start of one project could be described as tools for directing noticing when mentor teachers observe beginning teachers at work. The use of these noticing tools has spread well beyond the participating schools in the actual TLRI project. The university now uses the new judgement processes and resources with all their partner schools. They have supported other universities to work in this way too. Thus the immediate benefits experienced by the direct research participants have spread in ever-widening circles to other university staff, new cohorts of student teachers, new schools and mentor teachers in those schools, and, ultimately, to the students of all these people.

In the project that researched pedagogical techniques, which began with an explicit ‘pause and notice’ episode, there were also powerful impacts as both educators and student-teachers brought specific learning challenges into the open and discussed how these might best be addressed. Again, there was evidence that these new skills, consolidated during the research phase, had subsequently spread well beyond the original project.

- Several teacher-educators commented that some mentor teachers in schools have been impressed by the ‘pause and notice’ strategy when they see the studentteachers use it. They also began to model the practice in a supportive open classroom environment. In some cases the students have also become actively involved, calling for pauses when something puzzles them or they notice a need to pause and reflect.

- One teacher-educator now uses the ‘pause and notice’ strategy with teachers taking part in the Science Teaching Leadership Programme managed by the Royal Society on behalf of the government.[6] Over the course of a fellowship she has 12 days with these experienced teacher fellows, coaching them in processes for developing evidence-based explanations, getting them used to giving and receiving feedback in preparation for their leadership role when back at school, and generally supporting them to “refine their practice”. The co-facilitator in this work (not part of the original TLRI) also models the process now. Around 40 teachers take up these fellowships each year (20 or so per half-year span of a fellowship). That’s a very wide potential spread of impact via a channel that is one step removed from the intended target of the primary TLRI research (i.e. student-teachers).

There was also an element of noticing embedded in a self-assessment tool developed in the TLRI project that investigated transition challenges from school to university. This tool was designed to raise students’ awareness of the academic expectations they would face at university so that they could begin building stronger information literacy and academic writing skills while still in the supported environment of the final year at school. In this case the tool also served to raise practitioners’ awareness of these learning challenges, and hence provided the impetus for them to risk letting go some of their tight scaffolding of learning to ensure ‘success’ in NCEA assessments.

Ongoing learning from the creation of new tools

This theme is another that has been foreshadowed in the narratives above. When a research question is seen to be breaking new ground, it can be necessary to create new research tools that are fit for purpose: this was an area of big or moderate change for 69 percent of respondents (Figure 2). In several projects, interviewees said the development or adaptation of specific tools had strengthened the project design and findings and had also significantly influenced their practice.

| In one project the idea to adapt a rubric from the United Kingdom emerged following an early conversation between the project leader and the TLRI project monitor, in which they discussed the challenge of how to efficiently capture robust evidence of shifts in thinking and practice. The UK rubric was adapted by one researcher on the team who already had expertise in the area of information literacy. There had been no plan to make any specific resource at the outset of the project—the project leader said that creating a rubric was “a big new thing for us”. Even within the project the rubric was initially seen as “just a data collection tool” and only subsequently assumed greater importance as a teaching and learning resource.

Information literacy assumed more prominence as the project got underway and the lack of opportunities for secondary students to build their skills in this area became more apparent to the research team. This came to be understood as an underlying issue that was having an impact on their writing. Post-project the rubric has been posted online and tested in two tertiary courses. Because the tool is now online, data from responses can be accumulated electronically. All the TLRI project schools are still using the rubric with their final-year students, and its use has extended to at least three schools in Southland and three in the Wellington area. In a further development, two educational psychologists, both with expertise in quantitative analysis, have joined the team to co-explore the data being generated. |

This narrative shows how the metaphor of ripples in a pond can be used to describe an ever-widening sphere of influence for what actually began as a pragmatic solution to a data-capture challenge.

The next narrative is a little different in that the team always intended to create new tools as part of their work. Again, however, it is evident that impacts have continued to unfold well beyond the actual design stage.

| The project team that investigated mentoring actually developed three new tools. “Twenty questions” is a tool that probes teachers’ decision-making processes about what they value in a teacher. A series of vignettes was developed from the first sets of responses to this initial tool. In turn, these vignettes became a second tool to be used in professional development, with a focus on making judgements about student teachers’ suitability for teaching. A number of universities are now using both these tools in pre-service programmes and with mentor teachers. “In terms of the other TLRIs I’ve been engaged in, this has had a lot more impact because the research tools became professional development tools.” The third tool generated during the project is an online survey. This was ambitious and took a long time to develop. While respondents are thinking about their answers, the computer generates a profile about them as a decision maker. The project leader said that this tool still needs refinement and it has been taken offline in the meantime. |

6. Slower-burning impacts

In section 5 we described a number of impacts on teaching and learning that continued to reverberate though and beyond the life of the research. In those narratives there is already a sense that being involved in TLRI had personal impacts. Interviewees described changes to the way they saw something, did something, or simply ‘were’ as a person. All those we interviewed nominated these personal changes as the biggest impact of being involved in TLRI, and in some cases these changes had far-reaching consequences, such as providing the impetus for new career trajectories. Such slower-developing impacts are the focus of this section.

| “Powerful personal and professional changes and commitments have driven … participants to seek to extend and share their new learning.” |

Taking on new leadership challenges

New career trajectories can emerge as a consequence of involvement in TLRI. The narratives that follow suggest that the influence in play is not simply the kudos of successful involvement per se. Rather, powerful personal professional changes and commitments have driven each of these participants to seek to extend and share their new learning. In the first two narratives the researchers moved into positions from which they could affect change at an institutional level, which increased the likelihood of sustainability.

| One project leader has recently become Director of Teaching and Learning for a major school at her university. The project gave her a clear view of impediments to students’ success in their first-year courses, and in her new role she is in a position to do something about this challenge across the whole school, not just in her own classes. Together with a faculty member from the School of Education, she has planned workshops that explore transition challenges, with the aim of helping other faculty get a clearer understanding of NCEA, and how to better support first-year students. At the time of writing, this workshop had already been run on one of the university’s campuses, attracting 28 staff. Workshops had also been requested at two other campus sites.

One researcher described a moment of personal epiphany when she realised that the pedagogy being explored in her TLRI project could combine in powerful ways with the idea of culturally responsive pedagogy. She had been interested in the latter for some time and was able to combine the two sets of ideas to create powerful synergies for all the participants in the project at her university—both the other researchers and the student-teachers. Although not directly related to just this instance of intellectual leadership, she has now stepped up to a new leadership role in her faculty. |

The next two narratives come from practitioners in their respective TLRI projects. In one case the new leadership opportunities are associated with the move into the tertiary setting. The second narrative shows that expanded leadership opportunities can also be taken up as an extension of an existing teaching role.

| One of the practitioners in a TLRI project really relished the academic challenges of the TLRI research. As a more immediate consequence, he designed and led a TLIF[7] project at his school. Subsequently he was seconded into a university teacher education team, where he is able to share his insights and passion for developing new pedagogies in his subject area with a much bigger group of teachers.

Another practitioner (from a different TLRI project) said he had developed his own research-based skills through being involved in his project. “I wish I’d done it years ago”. This secondary teacher has stepped up to take a regional leadership role in a student research initiative funded by the Ministry of Education. The initiative involves asking questions about what local iwi think is important/significant in the history of the local area. He has drawn on his experiences in TLRI to build his skills for gathering oral transcripts from iwi. From these personal experiences he is building an oral literacy approach for students to use. He has “put himself in the kids’ shoes” as he has done this research and he is now much more confident to tap into local interest in the community. |

Again, the picture that emerges from these narratives is one of ever-widening ripples of impact, well beyond the original project focus.

Changing ways of ‘being’ a teacher (or a researcher)

In some cases, slower-developing impacts might be described as a type of threshold experience. Such an experience irreversibly changes the way a person understands their work—in this case, what it means to be a teacher and actions that are appropriate to that way of being.[8] For example, several of the researchers in the TLRI project that investigated the potential of ‘pause and notice’ coaching in initial teacher education said they could not go back to how they taught before. The next narrative demonstrates the key features of a threshold experience. Notice the strong emotional component: such experiences can be deeply troubling at first.

| One researcher described getting beyond the deeply held practice of “prepackaging learning” for students. He noted that smoothing the learning pathway for students has traditionally been seen as an important role for an effective teacher, and in recent years this thinking has “re-dominated” teacher thinking because of the systems of accountability around NCEA and competition between schools. “For teachers it is more important to manage the risk of failure than to try something different.” Now he believes that the process of learning is critical. If the delivery of “knowledge packages” dominates what happens in the classroom, students are deprived of opportunities to develop their information literacy skills, to become more independent in their learning, and to build deeper knowledge at the same time.

This teacher-educator said that he could never go back to his old ways of working, even when teachers want him to do so. This transformation did not happen suddenly, and initially he found his new insights upsetting. Thinking back over his many years of teaching he couldn’t help wondering “what might have been if…” However, he sees that the transformation has made him a better teacher-educator. He also thinks that many of the secondary teachers in his TLRI project experienced this same slow realisation, and that has allowed them to sustain their new practices beyond the life of the project |

| “This is another example where the familiar has been ‘made strange’ as a consequence of working in a TLRI partnership.” |

The application of insights about research per se

It is hardly surprising that being immersed in research has the potential to build new insights about research per se. However, the collection of narratives that follows offers more than the obvious learning point. In different ways, and in diverse contexts, insights from within research projects were applied in ways that changed other aspects of participants’ practice and professional thinking.

Changing ethical awareness

The next narrative, from the same practitioner as the narrative immediately above, involves a key insight about the ethical conduct of research. Figure 2 shows that just 49 percent of respondents said they had made a big or moderate change in this aspect of research. One reason for this could be that principal investigators, who typically lead this aspect of a project, are likely to feel they already have strong skills in ethical thinking. However, if really taking ethics into account was a new experience it had the potential to be very powerful.

| One researcher noted that those in the role of teacher-educators typically have strong existing relationships with teachers. This can lead them to take a more informal approach to research activities. It is easy to “gain consent and forge ahead” when relationships are already strong. The more formal ethics process of the TLRI provided an important opportunity to stop and think about “wider ethical issues” at the outset of the research, and to maintain an awareness of the “nuances of ethical practice” as the project unfolded. An example he gave was the importance and challenges of maintaining confidentially for senior secondary students. They are young adults for ethical purposes (and so have given their own consents) but are still treated much like all other school students in teacher discussions about learning, where confidentiality is seldom part of the frank, informal conversation dynamic. |

This is another example where the familiar has been ‘made strange’ as a consequence of working in a TLRI partnership. Teachers often talk informally about students during the course of a working day. Greater ethical awareness had given this newly fledged researcher pause to notice and think about the wider implications of doing so. This powerful experience is likely to stay with him and influence his future interactions with both teachers and students.

Supporting students-as-researchers

The next narrative also relates an emergent set of powerful insights that came about as a consequence of involving practitioners as research partners. This participation had the potential to open their eyes to the complexities of doing research, and this had implications for their ongoing day-to-day work.

| One teacher described how the project leader modelled techniques the teacher found very helpful for the development of his own research skills. He described a “growing realisation” of how important it was to model the research process for students so that they also had a clearer idea of what to do to undertake a research project. He now “feels strongly” about the importance of the role played by the outside person who shares knowledge and expertise with teachers in a project like this. He noted that teachers “don’t know what we don’t know.” |

Problems arise when teachers set research exercises but do not actively teach the research skills needed to complete those tasks.[9] The above narrative suggests that lack of awareness of what needs to be explicitly taught is at least part of the issue. Like the earlier narrative about the challenges of doing research with iwi, we see here how new insights into the complexities of undertaking research readily transfer to teaching and learning.

The next narrative continues this theme, this time showing a direct transfer from personal learning about a specific type of research challenge to the classroom context, with an associated raising of expectations about what students might be capable of achieving with the relevant support.

| A teacher from a low-decile school said her project gave her a structure to teach critical literacy skills such as advanced search skills and referencing. As a consequence of her own learning she now taught one senior class “to a standard we thought was too hard”. She could see ways to get the students to use these advanced skills, “and it worked”. |

During one TLRI project, final-year students and their teachers were brought into the university to experience the academic challenges students would soon face. As part of this experience they were shown a range of library databases and how to search these. As the next narrative shows, this could be useful learning that transferred to other parts of practitioners’ work.

| One practitioner said her school already had a password for open access to the university’s databases, but lacking the immediate know-how caused her to put off trying to access them, or she would not even think about doing so. Now she knew how to easily access the databases where she could find “good important information” to share with the other teachers in her team. (She is head of department.) For example, she had recently accessed readings from ERIC to support a professional learning day about effective writing. |

| “the very act of collaborating across tertiary institutions provides rich opportunities for ongoing learning.” |

Growing a personal repertoire of new research skills

The more experienced researchers also added to their knowledge and skills when they challenged themselves to try new data-gathering methods. For example, the use of video as a research tool was new for the research teams in two different projects. One project team used video as a self- study tool; this methodology was new for them. One of the less experienced members of the team became especially interested in self-study as a methodology. This is a research interest that he has continued to pursue. This team had initially planned to use a specific analysis package, but this was too costly so they had to devise their own method for analysing the ‘pauses’ they had captured on video. One member of the team said that this challenge had brought to their attention “a whole new body of research in using coaching in initial teacher education”.

The next narrative comes from a project where all the partners were university-based researchers. This narrative illustrates how the very act of collaborating across tertiary institutions provides rich opportunities for ongoing learning.

| Working with peers from another university was new for one teacher-educator. At the time the TLRI project began she had just completed her PhD, and this was her first chance to experience collaborative research. She became much more aware of the importance of negotiation; how different contexts affect innovation dynamics; “strength in diversity” as everyone brought their different perspectives and experiences to the team; and the benefit of collaborating on really “practical things”, such as sharing readings they found. It was also good to see the financial management systems of the partner university and how financial constraints can be managed. The small project team developed strong personal relationships, which she has since found useful for other aspects of her work (e.g. advice when marking postgraduate theses): “It built collegiality.” |

Slower-burning impacts for Māori learners

Both early childhood and school-level curricula emphasise the principle of establishing and maintaining partnerships between educational institutions and their immediate communities. Both sectors are also committed to honouring the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. With this principle in mind, several items were added to the survey to probe perceptions of impacts for Māori learners. If important new insights and/or practices were developed, did participants perceive that these had been shared and discussed with Māori families and whānau, or in the wider community? Figure 1 shows that survey respondents perceived lower levels of impact for these community-facing items: they are all ranked at the lower end of the response continuum. However, these results bear more critical scrutiny when slower-burning impacts are a focus for reflection.