He mihi | Acknowledgements

Teaching and Learning Research Institute (TLRI) for their generous funding.

To our Ngāi Tūāhuriri Rūnanga whānau, community whānau, and kura whānau, e kore e mutu ngā mihi. Thank you to our Ngāi Tūāhuriri poua, taua, and the various people and generations that graciously shared their stories.

Aunty Liz Kererū, nei a mātou mihi ki a koe e te māreikura, nā ō darlings o UC.

Mel Taite Pitama and Dot Singh, former and current tumuaki of Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

Aunty Lynne Harata Te Aika, Christine Harvey, Akeake Taiepa, and Tōmairangi Taiepa for contributing your amazing talents to the pūrākau process.

Riccarton High School media students Miriam McFie, Hine Tuitea Fendy Mei, and teacher Paddy Scott for filming and editing the hours of kōrero captured during our wānanga.

Rāhera Cowie, Te Hurinui Karaka Clarke, and many other UC colleagues who supported this kaupapa by attending the events, listening and encouraging us.

Māori Professors Angus Hikairo Macfarlane (Te Rū Rangahau) and Gail Gillon (Child Well-being Research Institute) for their continued encouragement, guidance, and support for Māori community partnerships and emerging Māori and non-Māori researchers.

Aroha ki te tangata, te tuahiwi ki te whai ao

Love for our people, at the ridge and beyond!—Te whakataukī o Te Kura o Tuahiwi

Introduction

Sharing ancestral stories as pūrākau is an ancient tradition in Māori culture, used throughout generations to transfer knowledge, teach traditional values, and promote communication. While often incorrectly relegated to the genre of “myths and legends”, pūrākau, as a traditional form of Māori narrative, is central to the sharing of philosophy, knowledge, culture, and worldviews (Lee, 2009). Engaging with shared stories draws heavily on oral language and listening comprehension, important skills for children to engage in the classroom and develop as literacy learners. Despite the cultural significance of pūrākau and their potential to enhance learning for ākonga, research on their effectiveness as a structured resource for early literacy development remains limited.

This research project, Ngā Pūrākau o Te Kura o Tuahiwi, explores the impact of Ngāi Tūāhuriri-specific pūrākau on literacy and identity development in bilingual and immersion classrooms at Te Kura o Tuahiwi. The study seeks to address the current gap in research by examining how place-based pūrākau can enhance early literacy development while fostering cultural identity within bilingual and immersion learning environments. Understanding the historical significance of pūrākau highlights their potential as meaningful tools for early literacy development, particularly in bilingual and immersion settings.

Ngāi Tahu is a principal iwi governing group in Te Waipounamu me Rakiura. Ngāi Tahu has 18 papatipu rūnanga; these ahi kā take the role of kaitiaki for the unique and plentiful land, sea, and natural resources in their domiciled areas (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, 2024). At a regional level, each rūnanga also advocates for the unique needs of their pakeke and tamariki in their work, social spheres, and educational pursuits. This collective voice ensures that Ngāi Tahu thoroughly represents their people at every echelon. For the University of Canterbury (UC), the rūnanga mana whenua group is Ngāi Tūāhuriri. Their marae is located 32 kilometres out of town in a pā settlement called Tuahiwi. Across the road from the marae is Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

Te Kura o Tuahiwi has over 170 tamariki in nine classes: four Level 1 Māori-medium and five Level 2 bilingual-medium. Many of their ākonga are Māori and whakapapa to the local Ngāi Tūāhuriri hapū. Te Kura o Tuahiwi is committed to revitalising and retaining te reo Māori and Mau ki Te Ako (Ngāi Tahu Education Plan). All ākonga learn te reo Māori, and the kura provides a choice of immersion level to whānau. In bilingual-medium classes (Puaka), tamariki follow the New Zealand Curriculum (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga Ministry of Education, 2025a), which teaches literacy and mathematics in English. Teachers use and teach reo Māori focusing on listening and speaking. In Māori-medium classes (Whitireia), tamariki learn in Māori contexts following Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga Ministry of Education, 2025b). Literacy and mathematics are taught in te reo Māori. As tamariki progress in reo Māori, English is introduced. All learning is measured against either curriculum document. This research proposed a collaboration between researchers at the Child Well-being Research Institute (CWRI), UC, Ngāi Tūāhuriri, and kaiako, whānau, and ākonga at Te Kura o Tuahiwi in North Canterbury.

Rationale

Secure cultural identity is a critical factor in the success of ākonga Māori (Macfarlane et al., 2015) and culturally rich learning environments, including using relevant resources for teaching and learning, which foster the development of a strong cultural identity.

Sharing quality books with children and elaborating on interesting words is one evidence-based way to foster children’s vocabulary learning (Justice et al., 2005). Research in New Zealand English-medium classrooms has reinforced this knowledge and shown significant benefits to children’s foundational literacy skills when quality book reading is incorporated into a classroom-based approach to literacy instruction (Gillon et al., 2019). This research built on that knowledge of how to support children’s early literacy learning in the classroom, extending to akomanga which have a focus on integrating te reo Māori into their teaching through the development of a set of pūrākau in the form of storybooks. These pūrākau were explicitly curated to capture the unique stories of Ngāi Tūāhuriri hapū as a resource to support children’s oral language development and their connection to Māori culture, stories, and language.

The pūrākau were the primary resource developed from this research. Alongside the important aspects of intergenerational knowledge transmission through this medium, the pūrākau provided a valuable resource for teaching and learning. Vocabulary embedded within the books scaffolded kaiako to use systematic, explicit elaboration of key vocabulary, contributing to part of this research. This systematic, explicit elaboration of vocabulary is an effective way to foster vocabulary learning in English-language contexts, but less is known about the effectiveness of this teaching strategy in the unique context of bilingual and rumaki classrooms (Hill, 2020; May, 2005), particularly given the broad spectrum language competency New Entrant ākonga bring to this space.

Building on 5 years of a national rollout of the better start literacy approach (BSLA), there was a clear gap recognised for New Zealand stories appropriate and accessible to young tamariki in their early years of literacy and language development, which incorporate integrated opportunities to learn new vocabulary, both in English and te reo Māori. Traditional pūrākau Māori are often very long, complex, and sometimes inappropriate for use as a class resource in many New Entrant classes. Further, early reading books that allow children to connect their classroom literacy instruction and their reading practice are limited, especially in a reo Māori context. Using place-based whānau-connected stories, such as the pūrākau produced, fostered a more profound sense of belonging and strengthened personal identity for Māori and Pākehā learners alike. The learning starts at the feet of ākonga, as they learn the stories of the ground they stand on.

Research questions

Primary research question:

- To ascertain the usefulness of pūrākau to bilingual and rumaki akomanga as an early literacy resource.

Subquestions:

- How do pūrākau resources impact bilingual and rumaki akomanga teaching and learning? (qualitative)

- How do pūrākau resources impact vocabulary and oral narrative learning in te reo Māori and English? (quantitative)

Overview of research activities

The project developed five pūrākau in te reo Māori, along with bilingual versions that were implemented into literacy teaching. It then assessed the impact on hapori identity and language.

These pūrākau were created based on previous research associated with the BSLA, a testament to our shared commitment to supporting young children in acquiring the necessary skills to be successful readers (Gillon et al., 2019). Te Kura o Tuahiwi, a key partner from the BSLA’s inception, was engaged in the BSLA in both Years 0–1 classrooms (English-medium and Māori-medium) through aligned funding with the Ministry of Education and A Better Start National Science Challenge. Since 2023, they have enrolled all their Years 0–3 junior classrooms: Kiwi (bilingual Years 0–1), Korimako (bilingual Years 2–3), Pīpīwharauroa (immersion Years 0–1) and Pīwakawaka (immersion Years 2–3). The pūrākau were used as part of the literacy teaching to enhance their structured literacy teaching further and provide a natural context for evaluating the pūrākau in early literacy teaching.

The research was structured into three distinct phases, each designed to address different aspects of the study’s overarching aim. The aims for each phase are outlined below.

Phase 1: Aim—To develop a series of pūrākau to use as an early literacy teaching resource in bilingual and rumaki classrooms.

Phase 1 was not directly associated with a research question; rather, it brought together the stakeholders to develop the five pūrākau for implementation in the school’s literacy approach. More details of this development appear below.

Phase 2: Aim: To undertake a qualitative exploration of the usefulness of pūrākau to bilingual and rumaki ākonga.

There is a growing collection of Māori resources, including traditional generic Māori pūrākau, available to both English-medium and kura kaupapa Māori. However, these resources are tailored for bilingual kaiako/ākonga and thus need adaptations to make them suitable for a dual-language approach (Hill, 2020; Jones, 2023). Through the research method of pūrākau, we sought to highlight and validate the experiences of kaiako and whānau who choose bilingual spaces for their tamariki and explore the ways in which tailored, localised rauemi may support or impact their learning engagement.

Phase 3: Aim: To evaluate the impact of explicit, systematic reo Māori vocabulary elaboration embedded within evidence-based literacy instruction.

Phase 3 evaluated the impact of the pūrākau developed in Phase 1 in reo Māori vocabulary learning of tamariki in both English- and Māori-medium New Entrant/ Year 1 classrooms at Te Kura o Tuahiwi. We gained permission from whānau to work with ākonga from across four different classroom contexts. Ākonga were engaged in evidence-based literacy instruction, which is already embedded into their classroom context (Gillon et al., 2019). The research used a pre-test and post-test design to investigate the expressive and receptive knowledge of elaborated and unelaborated vocabulary. This vocabulary included words from the shared book that were not systematically explained during the reading, and the study focused on tamariki before and after exposure to these words during shared reading over 10 teaching weeks.

Research design

Ko wai mātou: Developing a partnership research programme

Authentic partnership research is steeped in relationships and mutually shared values and goals. Our research team through UC CWRI is fortunate to have pre-established relationships with our iwi, Ngāi Tahu, and our rūnanga, Ngāi Tūāhuriri. Our teaching faculty also maintains an enduring relationship with Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

By engaging in continuous dialogue, we, as partners, explored the aspirations of both the school and hapū concerning identity and literacy achievement. We saw an opportunity to integrate the BSLA and the expertise areas of the research team to develop this project. It took ongoing collaboration to establish our shared goals and research design.

Kaupapa Māori research

This kaupapa Māori project is grounded in a kaupapa Māori methodology, ensuring that the research is conducted by Māori, for Māori, and for the benefit of Māori (G. H. Smith, 1990). This approach centres on Māori perspectives and highlights the transformational potential of the findings for Māori communities. To do this required all academics, regardless of our own whakapapa, to particularly exercise Kia tūpato (be cautious) and Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata (do not trample over the mana of the people) (L. T. Smith, 2021) to hear and deeply understand the aspirations of our mana whenua partners, Ngāi Tūāhuriri.

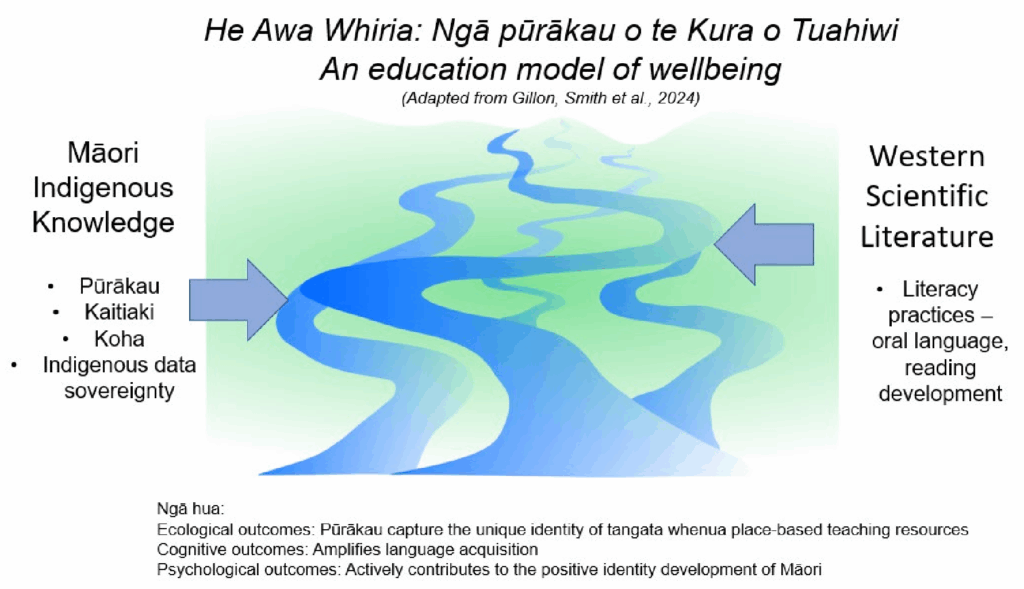

He awa whiria

He awa whiria, a methodological framework that promotes the braiding of Western science alongside Mātauranga Māori in the pursuit of the best outcomes for all tamariki (Gillon & Macfarlane, 2017; Macfarlane & Macfarlane, 2018). This framework was essential to our kaupapa because of the hegemonic nature of Eurocentric literacy science in New Zealand classrooms and teacher pedagogy (Gillon et al., 2024). Our methodological approach elevated Māori concepts to mana ōrite: Indigenous pūrākau as both taonga and pedagogy strengthened our understanding of data as a koha, our tuakana kaitiaki, and the importance of maintaining Indigenous data sovereignty. With the thoughtful braiding of these knowledge systems, we found synergy and developed effective strategies that honoured ancient ways of learning alongside modern classroom practices.

Te mahi a te kaitiaki

Engaging a kaitiaki is a key touchstone in a kaupapa Māori research to ensure research maintains relevance for mana whenua partners. This caretaker ensures that hapūcentric perspectives, values, and leadership are embedded in the research process. The kaitiaki work for this project was hugely variable, from providing cultural guardianship (setting and leading tikanga), guidance (advising on ethical issues), consultation (making connections), monitoring knowledge collection, and mediating between researchers and the community. This approach is fundamental when accessing Māori knowledge and taonga. Throughout various stages of the project, our kaitiaki demonstrated exceptional wisdom that contributed to calming the team. She played a pivotal role in fostering and sustaining relationships, established essential tikanga, provided steadfast leadership, and ensured that we remained focused on our objectives. Our kaitiaki advised and repositioned us to keep moving forward through COVID-19 restrictions, tangihanga, and other major hapū events.

Indigenous data sovereignty

Koha is a Māori word for a gift used to demonstrate gratitude (Mamaku, 2014). Koha comes in many forms: food, cash, a valuable cloak, an ornament or a contribution of time or knowledge (Mamaku, 2014). Bishop (1996) recognised koha as an appropriate research relationship metaphor, likening data collection to koha. The pūrākau shared by the local people is koha. Their koha come in the form of sharing taonga tuku iho: stories, experiences, and whakapapa.

The koha was generously given across each phase of the research project: in Phase 1, the collection of stories during the wānanga; for Phase 2, koha kōrero through semistructured interviews with hapori kura. Finally, in Phase 3, we obtained informed consent from whānau to gather language assessment data and ākonga assent to participate in the assessment. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Canterbury Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 2022/12), and all procedures were conducted per their guidelines.

Hapū have tino rangatiratanga, sovereignty to exercise control over their information, stories, and data (Kukutai & Taylor, 2016). The TLRI supported us in ensuring Ngāi Tūāhuriri retained intellectual property by recognising this in our contractual obligations. After the project, the koha from Ngāi Tūāhuriri (video of wānanga and publication proofs) were returned to them. We sought further clarification and consent from our kaitiaki, and a plan was made for appropriate dissemination and presentation. Our kaitiaki continues to guide us during this process. These mechanisms are straightforward ways for universities and funders to act in good faith under Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Quantitative approach

Quantitative methods were used to measure the impact of the pūrākau integrated into the classroom literacy program later in the project. These were braided with principles of whanaungatanga, kanohi kitea, and, of course, kai sharing.

These akomanga had already implemented the BSLA in their literacy approach. The pūrākau books would replace the existing resources in Building Block 1: Oral Language Development. Previously, the storybooks used in this teaching block were generic reo Māori or English picture books prescribed by the approach.

Adapted literacy approach

The adapted literacy approach used an exploratory pre-test/post-test design to examine the effects of systematic and explicit vocabulary elaboration during shared reading on children’s expressive and receptive vocabulary. The focus was on enhancing vocabulary skills by providing in-depth explanations and contextual usage of targeted words during the shared reading sessions.

Participants

The study involved 46 children from Te Kura o Tuahiwi, split between two types of immersion classes:

- 18 children were enrolled in a Level 1 full-immersion reo Māori class (80%-100% Māori language).

- 28 children were in a Level 2 bilingual class (51%-80% Māori language).

Procedure

The intervention was conducted over Term 1, a 10-week period in the 2024 school year. A pre-test was administered at the beginning of Term 1, and a post-test was completed at the start of Term 2 after the intervention.

Professional learning for teachers

Before the intervention began, all five participating teachers underwent a 1-day professional learning workshop. This training included:

- discussion of aspirations and challenges for Māori language learning

- the importance of vocabulary development for children’s literacy

- an overview of the intervention’s resources, lesson plans, and teaching techniques.

Following the workshop, teachers received support through lesson modelling, observations, and written feedback, totalling about 10 hours of guidance over the 10 weeks.

Assessment

The assessment was conducted using two different language measures.

Vocabulary probes: Children were assessed on 20 tier-2 words from the storybooks used in the intervention for both receptive and expressive knowledge. Half of these words were targeted and elaborated upon during shared reading, while the other half were presented without further explanation (referred to as unelaborated).

- Receptive vocabulary probe: Children were shown four pictures and asked to identify the word corresponding to the target vocabulary. Foils included phonological, semantic, and unrelated distractors.

- Expressive vocabulary probe: Children were asked to define and use the target word in a sentence. Their responses were scored on a 0–2 scale, based on knowledge completeness.

Oral narrative task: Children participated in a story retell activity using a bilingual story adapted from a validated English version. They retold the story, progressing through illustrated pages and responding to prompts if needed. Following the retell, comprehension was evaluated through factual and inferential questions.

Teaching intervention

The intervention centred on five pūrākau developed collaboratively as part of Phase 1 of the project. The stories were used to support both vocabulary development and oral narrative skills. Teachers used each storybook twice over a 10-week period, with 4 weekly lessons designed to deepen understanding of both vocabulary and story structure.

Key teaching goals included the following.

- Systematically elaborating on target vocabulary words within the stories. The elaboration technique consisted of defining the target word in the moment, during the reading of the story, and using it in a sentence that related to the context of the story.

- Building knowledge of story sequencing and structure, such as characters, settings, problems, and solutions.

- Encouraging students to retell parts of the story and relate them to personal experiences.

The lessons incorporated a variety of activities designed to improve both vocabulary knowledge and oral narrative skills, which are critical for later literacy success. Teachers were supported with detailed lesson plans for each lesson and integrated vocabulary elaboration prompts within the storybooks using Post-it notes. See below for an example lesson plan and an example of the vocabulary prompt within a pukapuka. A summary of the 10 weeks of teaching can be found as Appendix 2.

TABLE 1. Lesson plan example: week 3, day 1

| Day 1: INTRODUCE, READ and ELABORATE

Introduce the target words for the week: “This week we are going to learn some new words.” Place each target word card on the board as you introduce the word and its definition. E.g., “Our first word is entrance – an entrance lets you go into a place. Our next word is mimic – mimic means to copy. This word says tirohanga – tirohanga means to view something. Our last word is whakaahua – whakaahua is a photograph.” Introduce the story by completing a walk-through of the book. Focus on the key elements of the story and use the pictures in the story to support your walk through. Include the target vocabulary in your walk-through. Introduce the story grammar element of ‘character/kiripuaki’. Display the A4 word card on the board. This word says character. A character is who the story is about. The characters are usually introduced at the beginning of the story. Let’s find the characters in this story. Put your hand up when I introduce a new character in the story. Ko tēnei kupu he kiripuaki. Ka tuhi tēnei pukapuka e pā ana ki te māhi o tēnei kiripuaki. Whakauru ai ngā kiripuaki i te tīmatanga o te pukapuka. Ko wai ngā kiripuaki kei roto i tēnei pukapuka? Ā te wā kōrero au e pā ana ki tētahi kiripuaki hou, whakatū tōu ringa. Read the story from start to finish, pausing on pages with post-it notes to elaborate on the target word. Use written prompts in the book to introduce and elaborate the vocabulary words. After reading the story, review the characters. Who were the main characters in this story? Yes, Wīhitora is a character in our story. Māia is another character in our story. Aunty Remona and Aunty Liz are other characters in our story. Ko wai ngā kiripuaki mātāmua i te pukapuka nei? Āe ko Wīhitora te kiripuaki mātāmua. Ko Māia tētahi atu kiripuaki. Ko Aunty Liz rāua ko Aunty Mona ngā kiripuaki hoki. |

Details of Phase 1: Pūrākau development process

The co-creation of pūrākau

Three full-day wānanga were held at Tuahiwi Marae to collect hapū stories—a widely shared pānui invited whānau participation, with many kaumātua sharing memories. Key kōrero were identified for retelling in a picture book format. In response to community feedback, both audio and video recordings were made. Over 30 hours of kōrero from 28 contributors across four generations were gathered, with some stories captured outside the wānanga. The research team storyboarded key themes, people, and places from the wānanga. Later in the process, older rangatahi provided input and received a koha for their contributions.

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 2. A special thanks to those who contributed their kōrero to the project:

Aoraki, Aunty Jenny, Aunty Reimona, Aunty Liz, Aunty Tāwhai, Aunty Gloria, Aunty Hutika, Deidre, Greg, Halle, Hippy, Willy, Rex, Maaka, Ivan, Joseph, Mārewa, Mathias, Nukuroa, Gail, Ruth, and Janice

Language use

The hapū opted for the Ngā Tūāhuriri “ng” over the Ngāi Tahu “k” dialect and included kīwaha and whakataukī in both versions. The reo Māori script followed the same storyline as the bilingual version but wasn’t a direct translation, ensuring natural language flow for learners.

|

|

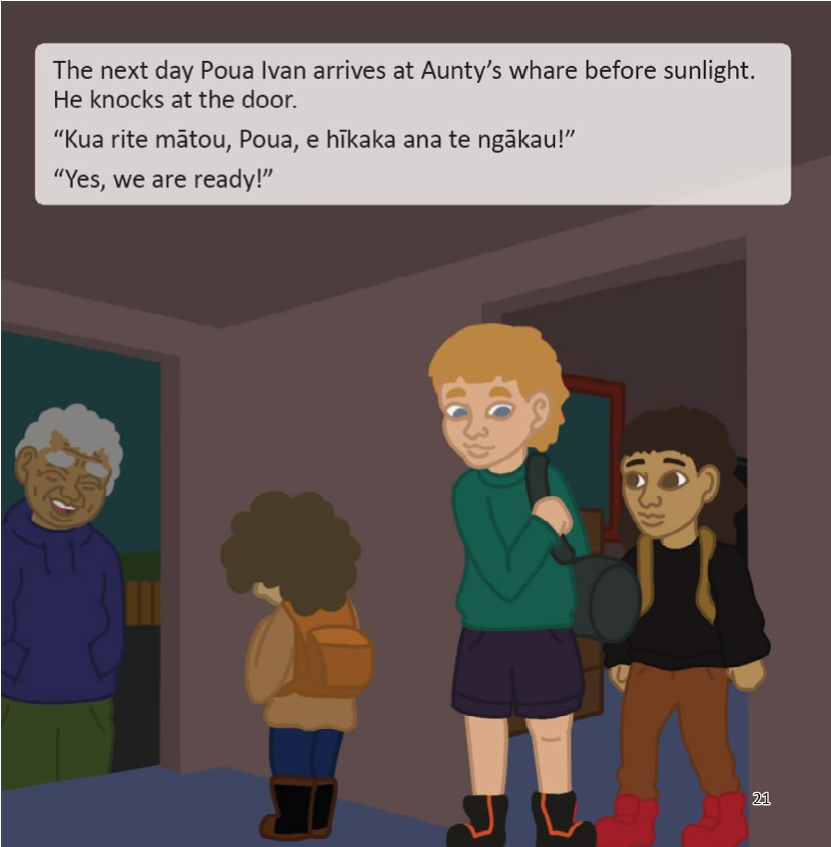

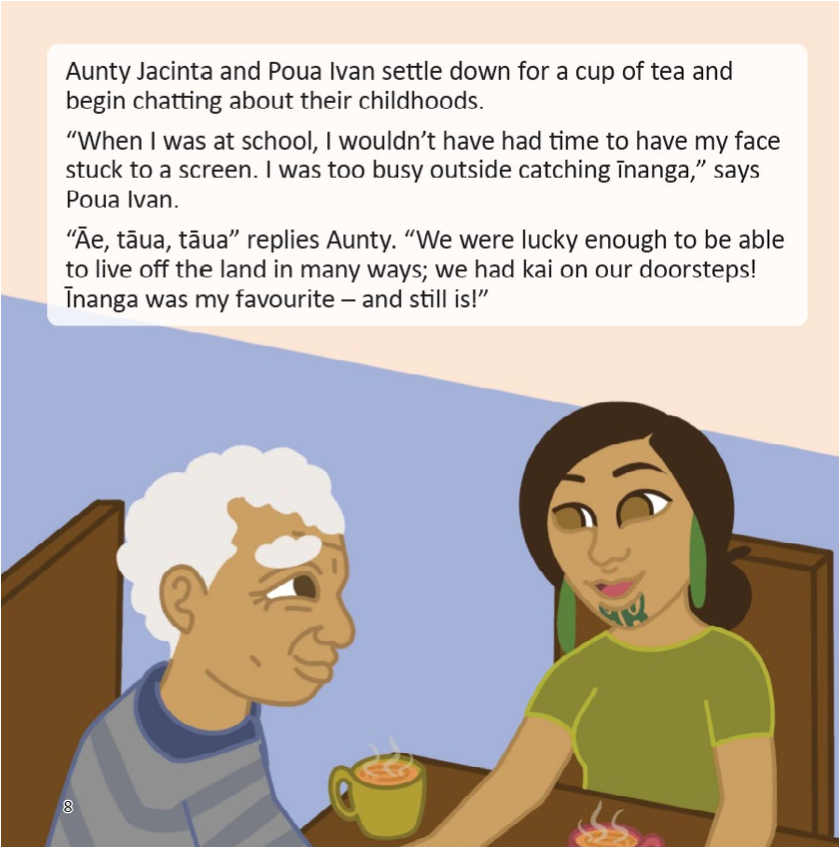

FIGURE 3. From A Day with Poua Ivan (pp. 8. & 21), examples of whole sentence and single-word substitution and kīwaha use

Illustration and production

Hapū-associated artists illustrated five storylines. Each book underwent two rounds of revisions before finalising. A layout designer integrated text and imagery, creating unique formats.

Additional content

Each pukapuka included school values, whakapapa connections, and literacy support sections.

Launch and celebration

Following printing, the books were blessed at a whakamoemiti and officially launched at the Ngahuru celebrations with a pōwhiri, speeches, and performances.

|

|

FIGURE 4. Launch celebrations

Ngā pūrākau

|

|

Whanaungatanga | A Day with Poua Ivan

Based on kōrero from Poua Ivan Rupene-Ryan, Maaka Tau, Mārewa Hoeta, Mathias Pitama, Poua William Rex Anglem, Poua Willy Tau, Poua Hippy, and Aoraki Brennan.

Young people’s reliance on cellphones for entertainment concerns the kaumātua of Tuahiwi. Instead, they emphasised the value of outdoor activities, traditional mahinga kai, and learning from the environment. They also discussed the impact of pollution on the depletion of the īnanga species and the need for sustainable harvesting practices. A fictional story was produced about a day with Poua Ivan, a well-known figure from the pā. In this pūrākau, we meet Poua Ivan as he visited Whaea Jacinta, Meihana, Xavier, and Kyro with some īnanga. This story is part of documenting Ivan’s frequent trips with local boys to the river to practice the traditional gathering of īnanga. During these haerenga, Poua Ivan teaches about mahinga kai and the importance of looking after the community through whanaungatanga. The illustrations include Ivan’s iconic classic red and white waka noho and the school uniform.

|

|

He Haerenga ki Kaiapoi Pā | A Trip to Kaiapoi Pā

Based on kōrero from Joseph Hullen.

The pūrākau of the Kaiapoi Pā is a koha from Joseph. He spoke at length about the stronghold of Kaiapoi Pā and its importance for trade and commerce compared to well-known trade spots such as Dubai. He sees Kaiapoi Pā as a metaphor for trade, carrying on the kaihaukai whakawhanaungatanga ethos. He spoke extensively about the scientific acumen of his tūpuna and the scientific innovations that have happened in Tuahiwi since their tūpuna arrived at the site of the pā. There were innovative practices to cultivate kūmara and functional adjustments to everyday things to increase the food supply. He shared his knowledge of the looming threat of climate change and how mātauranga Māori might hold the solutions. In this pūrākau, Henare’s Te Kura o Tuahiwi project became the impetus for Maaka to take him out to Kaiapoi Pā to share its rich history of innovation and spark ideas for him to take back to share with his class.

|

|

Hine Rēhia | Kapa Haka at Tuahiwi

Based on kōrero from Aunty Liz Kererū, Aunty Reimona, and Aunty Hutika.

Many kōrero reflected the special place of kapa haka for the hapū. The waiata in this pukapuka was composed by Aunty Liz to teach the tamariki of Tuahiwi about the karanga process, about some of the kaumātua at Tuahiwi, Te Hāhi Rātana, as well as the important places in Tuahiwi, such as the whare: Maahunui, and the wharekai: Te Ao Mārama. Their kapa haka group, Pīpīwharauroa, and the musical background of Tuahiwi are the epitome of the Tūāhuriri identity. They spoke of the kapa haka tournaments and older generations composing waiata and teaching them how to perform. They explained how all these waiata had historical purposes and could not be sung in the current context. It was essential to capture this passion in a pūrākau for this hapū. This story focuses on Whitiora and her growth within her own kapa haka journey to overcome performance anxiety and become a strong performer. After expert tutorage and lots of practice, she stood with her peers, then kaumātua at Te Papa. The illustrations, done in Akeake’s unique style, were exciting for ākonga.

|

|

Matariki ki Tuahiwi | Matariki at Tuahiwi

Based on kōrero from Poua Ivan Rupene-Ryan, Greg Byrnes, Maaka Tau, Mathias Pitama, Joseph Hullen, and Aoraki Brennan.

Matariki at Tuahiwi is a time for whānau to gather, especially after returning from the Mutton Bird Islands or gathering pounamu. The celebrations often included kai, with mahinga kai being the preferred food-sourcing method. Hapū members would fish for tuna, gather watercress, pipi, and cockles, and even pick mushrooms at a paddock on the Five Crossroads. During the wānanga, the older generations often lamented the pollution of mahinga kai sites and emphasised the importance of teaching the next generation about their relationship to the whenua, wai, and significance of mahinga kai practices. This pūrākau focused on a three generational whānau, Mathias, Sheldon, and Te Koha, who went to gather the essentials from the supermarket. Mathias takes the time to remind his whanaunga of traditional gathering practices, memorable landmarks and the true purpose of Matariki for Ngāi Tūāhuriri: “Mā te tohatoha kai, ka ora ai te iwi” the importance of sharing kai for the good of the iwi.

|

|

Taku Tipuranga | The Pā Kids

Based on kōrero from Aunty Tawhai Kimera, Aunty Liz Kererū, Maaka Tau, Mārewa Hoeta, and Joseph Hullen.

This pūrākau is based on the rich history of the pā shared through by many wānanga contributions. As they reminisced on their youth and experiences on the pā, they shared stories of the draughty cold wharenui, the memorial fence, and the stage where they gave concerts and sang waiata. One of their clearest memories is of the concert they gave when Prime Minister Norman Kirk visited the wharenui. They also spoke of their duties and the fun they had. They giggled as they remembered being told off for jumping on the mattresses in the mattress room. Lastly, Aunty Liz spoke of how they did not understand its value when they were children but now appreciate its profound importance. This pūrākau is set on a rainy day in Tuahiwi. Te Amo is bored at his taua’s house. Together, Te Amo and Taua Tawhai explore a photo album of key pā events and memories. Maaka and Mārewa turn up to share their memories, too.

Findings from Phase 2: Qualitative exploration

Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi had a direct impact on the hapori right from the initial hui when mātāpuputu (elderly) and other generations of Ngāi Tūāhuriri members joined together. The series of hui were opportunities to share localised stories and histories; many whānau members had not seen each other for many years. The notion of kotahitanga had an impact, with many commenting that they often get together, similarly for tangihanga, so it was nice for them to come together for a happy kaupapa. Tuahiwi Marae was open to reminiscing, voicing the narratives important to them, and sharing unique pūrākau about their upbringing and links to the land and awa.

There was a sense of joy, whanaungatanga, and empowerment that their experiences and narrative within a “te ao Māori” context were valid and a taonga for future generations. The positive impacts of both the process (coming together as a hapori), and the creation of the pukapuka and film archive were instant and ongoing.

Pūrākau, a forever taonga

Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi are a “forever” taonga that sits within the hapū and local marae which has mana and control over further distribution. Although the books were used at the local school for integration into early years reading, the “hua” or impact can be seen, heard, and felt much wider.

On the day of the whakamoemiti, where the books received a blessing, local hapū members demonstrated happiness, laughter, and heartfelt emotion at the creation of local stories about “them”, with their poua, taua, and other important stalwarts on display. They could recognise the faces, and the important features of their whenua, marae, and events that mattered to them—seeing Poua Ivan’s distinct caravan was a hit. There were tears, excitement, and a want from the hapū to continue this journey of bringing their local pūrākau alive. As all hapū do, they have the mātauranga and capability, therefore those within the iwi can take on the mantle to continue story collection and holding these taonga for future generations to learn from. The impacts of the pukapuka on the hapori are various, including increased use of te reo Māori due to the bilingual and Māori only versions of the pukapuka. The localised stories that can be seen, heard, and felt through the pūrākau has a direct impact on the uri and future generations of the hapū, to learn from the lessons and innovation of their tūpuna.

Another element of the pukapuka is moving beyond mana ōrite to mana motuhake; the hapū have self-determination and control over their histories, stories, and futures. These pukapuka (albeit in a small way, perhaps) support mana motuhake because the power of their stories, how they are told, and who they are told to sits with Ngāi Tūāhuriri. The pukapuka are a taonga, not merely because they express the stories from the past, but they also show the faces and pūrākau of our tamariki at Tuahiwi kura now. This was expressed by one of the Whitireia kaiako:

I haere mai au ki tō Launch, ki te marae, he tino harikoa au, i tino waimarie, ka titiro ki ngā taonga, ki ngā tamariki hoki, ka kite au i ngā tamariki kei roto i ngā pukapuka, mīharo kē. (Whitireia Kaiako 2, 2024).

Language revitalisation and development

A further direct and ongoing impact of the pukapuka on the hapori is language revitalisation, both through its use in the school and its filter through to whānau. Te Kura o Tuahiwi is now a full Māori-medium school across two differing levels of immersion. There has been a steady increase in the number of whānau deciding to enrol their children in both Level 1 (81– 100% reo Māori instruction) and Level 2 programmes (51– 80% reo Māori instruction) across Aotearoa New Zealand (Jones, 2023). Table 2 shows that the preferred kaupapa Māori-medium of education is Level 1 immersion, mostly kura kaupapa Māori. Similarly, Level 2 bilingual programme enrolments have increased in numbers over the years.

| Māori Language Immersion Instruction |

2010 | 2015 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | Increase Since 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (81–100%) | 11, 738 | 12, 958 | 15, 043 | 16,746 | 17, 313 | 5,575 |

| Level 2 (51–80% te reo | 4, 587 | 4, 884 | 5, 468 | 5, 645 | 5, 848 | 1, 261 |

Note: Ministry of Education. (2021)

At Te Kura o Tuahiwi, the school decided, encouraged by a desire from the hapori, to move Puaka to a higher level of immersion. For many years, Puaka sat at Level 3 immersion (31% to 50% reo Māori instruction) under English-medium education (Ministry of Education., 2024). Whitireia also increased in terms of immersion level from Level 2 to Level 1. The proposal and subsequent decision to increase the level of reo Māori output across the school was encouraged by whānau and local hapū, Ngāi Tūāhuriri. As kaiako and whānau interviews demonstrated, the pukapuka were a great way to support the increased reo Māori instruction levels in both Puaka and Whitireia:

You were able to really see their [the children’s] growing understanding. (Whitireia Kaiako 1, 2024)

Although there is a growing understanding of te reo Māori in Whitireia, the dominant and comfortable language of output for many (at this stage) is English:

Their output is quite variable. So, most of them will respond easily to instructional language. But mostly they will respond in English. There’s a few of them who are starting to independently kōrero in Māori. (Whitireia Kaiako 1, 2024).

This kaiako explained that there is a spectrum of reo Māori capability in the junior Whitireia class, most do not come from reo Māori speaking homes and, in her opinion, she would “describe this space as working towards level one most of the time” (Whitireia Kaiako 1, 2024). Similarly, one of the junior Puaka teachers explained:

The whānau are on their learning journey as well, especially if they’ve been put into Puaka stream … but you know they’re on the waka because they want their kids to [kōrero Māori] … I think in our space it just gives people the opportunity to be on that learning journey. But for me, I’m not quite, if I’m being realistic, I’m not there at doing that, 51 to 80%. (Puaka Kaiako 1, 2024)

Both the Whitireia and Puaka kaiako shared their appreciation for the pukapuka and expressed how their regular use supported reo Māori development for their tamariki at different levels of immersion. They explained most whānau across Whitireia and Puaka have developing reo Māori capability, but they are on a journey of learning alongside their tamariki, and they too as kaiako were also increasing their reo fluency. These pukapuka and the kupu hou (new vocabulary) within them will support ongoing proficiency development:

I think I’m nearly there, and my kids do a lot. We use a lot of reo. The books were great for that and the process of it was, you’ve got to do things multiple times before it sinks in and it becomes part of your everyday language. (Puaka Kaiako 1, 2024)

Identity development

I put her at Tuahiwi because I wanted her to grow up unlike me, comfortable in her own skin. (Whānau 1, 2024)

A common notion that came through interviews with kaiako and whānau, as well as informal discussion, is that many choose to enrol their tamaiti at Te Kura o Tuahiwi to give them a different, more culturally empowering experience. They want their mokopuna to have the reo and be confident as Māori. Well-known identity markers within the Māori world are whakapapa (genealogy), pepeha (a tribal affiliation), and geographical links (Jones, 2023; Te Huia, 2015). These identity markers are how Māori connect with past, present, and future (Te Huia, 2015). The pukapuka impacts and supports identity development. Tamariki reading them are privy to seeing their whānau, or even themselves or people they recognise from their kura on display in a positive light. Ngāi Māori and their ways of being are highlighted with pride in the pūrākau, and the kaupapa are relatable. A sense of belonging and connection can be felt for tamariki and their whānau because the places and experiences expressed in the pukapuka are known. The tamariki can (and have) stood on the whenua at Kaiapoi Pā. Many have stood in the local kapa haka competition Kā Matakura o Ruataniwha, similar to Whitiora in the Hine Rēhia narrative. The pukapuka help bring day-to-day occurrences in the life of the tamariki alive, and the reo Māori within them is accessible because of the two versions.

For whānau, yes, they want the reo for their babies, but they also want them to access a form of education different from their childhood. They expressed a desire for kaupapa Māori infused education where ancestral language supports identity development and confidence differently from what they experienced growing up:

We just want that foundation for her, and not to get older, and just struggle and feel like they didn’t know anything. (Whānau 2, 2024)

Connectedness, belonging, and self-pride as Māori can be achieved in Māori immersion teaching and learning spaces (Jones, 2023), and this can be supported by rauemi like Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi.

Lack of resources in Māori immersion education

Although there have been significant developments at the school and in bilingual education more widely, the lack of adequate resources for bilingual spaces remains today (Jones, 2023; Hill, 2020). One kaiako from Whitireia expressed “lack of resourcing, it’s just barrier after barrier … well a lot of what we’re using, that’s us creating those (resources) yeah laminating things, just so much extra (work), another layer” (Whitireia Kaiako 1, 2024). Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi were a resource that supported accessibility for both the bilingual ākonga and kaiako on their journey of developing te reo Māori. Puaka Kaiako 1 (2024) was perplexed at the limited resources in Aotearoa New Zealand schools compared to her teaching experience in the UK. She was particularly surprised at the limited Māori resources:

So, for me, I’ve been doing the BSLA program since I got back, and the quality picture books have been a key part of the process and learning … .So the pūrākau just followed the same system as what I’ve been working in … .What I liked about the 5 pūrākau was they were of here. They gave context to the book, (be)cause to find books that just suit your kaupapa, you gotta do a lot of research.

Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi were unique and distinct to the area and built on the localised curriculum that Te Kura o Tuahiwi aimed to employ across the school. Māori immersion teachers find it difficult to source contextual, place-based resources, and a further challenge and nuance is the suitability of the level of reo for their tamariki. These pukapuka were deemed appropriate due to having both a bilingual, more accessible version, still with a range of phrases, links to Māori values and sentence structures, and a reo Māori only version. This allows for growth and development in te reo Māori over time.

Findings from Phase 3: Quantitative analysis

Results

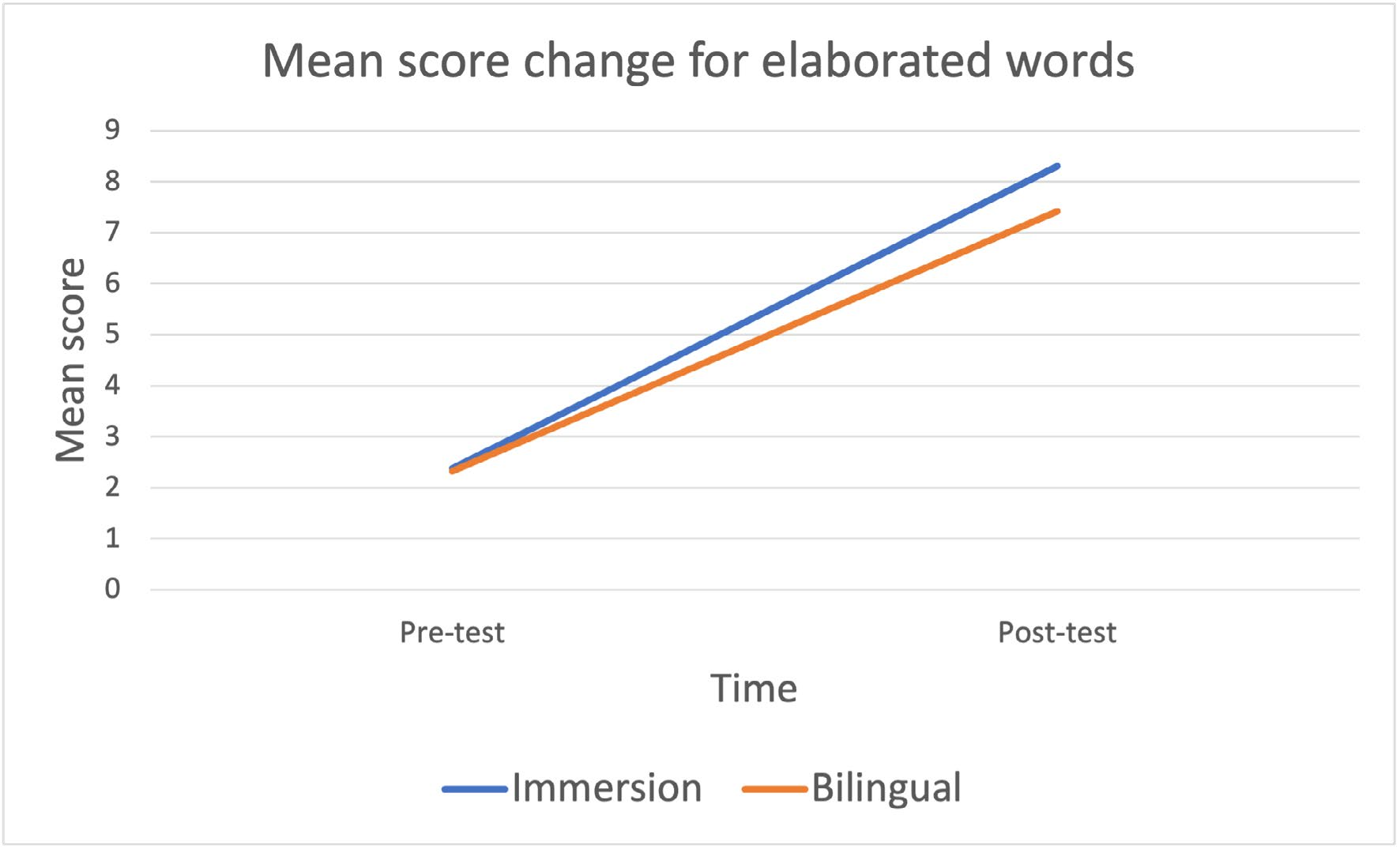

Preliminary analyses demonstrate a statistically significant impact growth in children’s expressive and receptive vocabulary, over the 10 weeks of teaching. This impact was equally great for children in the bilingual and immersion classes.

Figure 6 presents the mean change in scores for elaborated words for both immersion and bilingual classes. A mixed ANOVA analysis showed significant main effect of time (F(1,38)=100.52F(1, 38) = 100.52F(1,38)=100.52, p<.001p < .001p<.001, ηp2=.726\eta_p^2 = .726ηp2=.726), indicating growth in elaborated word knowledge between pre and postintervention measurement points. There was no significant effect of class type, indicating no overall difference in scores between immersion and bilingual language learning contexts (F(1,38)=0.361F(1, 38) = 0.361F(1,38)=0.361, p=.551p = .551p=.551, ηp2=.009\eta_p^2 = .009ηp2=.009).

Further analyses in future publications will examine in more detail the impact of the elaboration technique on Māori versus English words; the types of responses children made on the receptive language task (specifically, whether incorrect responses demonstrated a semantic or phonologic bias); and the oral narrative language samples, focusing on changes in the quality and quantity of language used, as well as the development of story structure features.

Implications for kaiako

Supporting kaiako in using evidence-based vocabulary teaching techniques positively impacts children’s language development. This phase of the project contributed to enhancing teaching practice using place-based pūrākau, to foster children’s language development—both vocabulary and story retell—both of which are important contributors to children’s later reading comprehension success. Kaiako can use the evidence-based vocabulary elaboration strategy across all curriculum areas, and for both new English words and kupu Māori, fostering language-rich learning opportunities all throughout the school day.

Conclusion

He kai kei aku ringa

Ngā Pūrākau o Te Kura o Tuahiwi had an immediate and long-lasting positive impact on the local hapū and kura. Pūrākau foster mana motuhake, kotahitanga, and whanaungatanga while revitalising te reo Māori. Integrating these stories into classroom literacy increased reo Māori acquisition for ākonga and hapori while contributing to the growing level of immersion at the kura.

Schools and centres continue to look for opportunities to enhance their programmes through recognising and adapting their practice to reflect better tangata whenua in learning programmes to meet education’s bicultural aspirations. This study is a beautiful example of how taking time to build relationships and finding spaces of authentic collaboration can locate the nexus of academic enrichment and identity-affirming learning. We suggest that any schools hoping to achieve similar results take the time to get to know their mana whenua partners, seeing collaboration as a lifetime of work and reciprocity.

Nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi

This project is the culmination of the aspirations of Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Te Kura o Tuahiwi, kaiako, and whānau. With the increased enrolment in Māori-medium education programmes, these pūrākau are beneficial in supporting increased levels of reo Māori instruction and identity development, providing the Ngāi Tūāhuriri mokopuna with a culturally empowering experience and a sense of connection to their pā.

As bilingual teachers continue to serve at the chalkface of language revitalisation, providing them with bespoke resources enables them to focus on what they do best— teaching! Continuous relevant professional development further strengthens their ability to make meaningful literacy learning more effective for bilingual learners.

He awa whiria

Reading and writing literacy practices are grounded in Western learning traditions, whereas Māori literacy is traditionally utilised in oral traditions. Finding synergies between these epistemologies requires mana ōrite approaches. The findings demonstrate that explicit vocabulary elaboration techniques, when integrated with pūrākau pedagogy, significantly enhance children’s expressive and receptive vocabulary in both bilingual and immersion settings, reinforcing the importance of a mana ōrite approach to language learning. Ultimately, there is transformative potential for braiding Māori and Western knowledge systems to create a path forward for bicultural education in Aotearoa that is both academically enriching and culturally affirming.

Project team

Jen Smith, Aunty Liz Kererū, Amy Scott, and Kay-Lee Jones

Kaitiaki, Liz Kererū (Ngāi Tūāhuriri) is a māmā, a kaiako, kaikaranga, and kaihaka. He wahine marae ia. She is the kaitiaki of this kaupapa. Famously known as Aunty Liz to all, she lent her mātauranga, her passion, her expertise in tikanga, and her mana to this project in service of her people.

Principal investigator, Jen Smith (Ngāti Whātua, Te Roroa, Ngāpuhi) is a senior lecturer in Māori education in the Faculty of Education at the University of Canterbury (UC). In addition to her lectureship, she leads culturally responsive education in Te Kāhui Pā Harakeke: The Child Well-being Research Institute at UC. Jen is an experienced primary education teacher. Jen’s research in culturally responsive pedagogies underpins her expertise in Māori educational experiences and wellbeing. Her research leadership has recently focused on culturally responsive strategies that enhance literacy engagement through the national BSLA.

Associate investigator, Dr Kay-Lee Jones (Te Aitanga a Māhaki, Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau a Kai, Te Whakatōhea) serves as a senior lecturer in teacher education at the University of Canterbury. With extensive experience in kaupapa Māori and bilingual education in Aotearoa New Zealand, she teaches initial education and postgraduate courses in mātauranga Māori, culturally responsive practice, and language revitalisation. She is a mother of three tamariki of Māori, Samoan whakapapa, enrolled in kaupapa Māori education.

Associate Investigator, Dr Amy Scott is a senior lecturer in the UC Child Well-being Research Institute with a background in speech-language therapy. Now a researcher in literacy, Dr Scott is passionate about advancing children’s literacy and language development, particularly within the classroom context. She also serves as the programme coordinator for the BSLA microcredentials, where she is committed to supporting the future of literacy education.

He kuputaka | Glossary

| ahi kā | home fires of occupation |

| ākonga | student |

| akomanga | classroom |

| awa | river |

| haerenga | journey |

| hapori | community |

| hapū | kinship group from a wider iwi affiliation |

| he awa whiria | a braided river; framework based on braided rivers in the landscape of Te Waipounamu |

| hua | a consequence |

| hui | gathering |

| īnanga | whitebait |

| iwi | extended kinship group made of hapū groups |

| kaiako | teacher |

| Kaiapoi Pā | a traditional Māori settlement north of Ōtautahi |

| kaihaukai | reciprocal gift of food by one kinship group to another |

| kaitiaki | guardian or steward, singular and collective |

| kapa haka | Māori performing group |

| karanga | formal or ceremonial call |

| kaumātua | older people |

| kaupapa | matter of discussion |

| kīwaha | colloquialism |

| kohinga kai | food gathering |

| kōrero | to speak |

| kotahitanga | unity, togetherness |

| kupu hou | new vocabulary |

| kura | school |

| mahinga kai | food-gathering place |

| mana | a supernatural force in a person, place, or object |

| mana motuhake | self-determination |

| mana ōrite | equity, equal mana |

| mana whenua | territorial rights |

| marae | a traditional complex of buildings |

| mātāpuputu | elders |

| matariki | a cluster of stars that signify the change of year |

| mātauranga | knowledge |

| mātauranga Māori | Māori knowledges |

| mokopuna | grandchildren, descendants |

| Ngāi Māori | Māori people |

| pā | a traditional fortified settlement |

| pakeke | adult |

| pānui | a notice |

| papatipu rūnanga | tribal council of ancestral land |

| poua | grandfather or elderly man |

| pounamu | a highly prized greenstone |

| pūhā | native small leafy plant |

| pukapuka | book |

| pūrākau | ancestral story |

| rangatahi | young generation |

| rauemi | resource |

| rūnanga | tribal council |

| tamaiti | child |

| tamariki | children |

| tangata tiriti | people of the treaty, non-Māori |

| tangata whenua | indigenous people |

| tangihanga | Māori funeral ceremonies |

| taonga | treasure |

| taonga tuku iho | intergenerationally transmitted treasure |

| taua | grandmother or elder women |

| Te Waipounamu and Rakiura | the two most southern islands of New Zealand |

| tikanga | Māori customs |

| tino rangatiratanga | sovereignty |

| Tuahiwi | settlement north of Ōtautahi |

| tuna | eel |

| tūpuna | ancestors |

| wai | water |

| waiata | song |

| waka noho | caravan |

| wānanga | a gathering to transfer knowledge |

| whakaaro | thoughts and feelings |

| whakamoemiti | a blessing ceremony |

| whakapapa | genealogy |

| whakataukī | proverb |

| whānau | family in its broadest sense |

| whanaungatanga | connecting through relationships |

| whare | a house |

| wharekai | a house specifically for food |

| wharenui | a traditional meeting house |

| whenua | land |

| uri | descendants |

Please note that our translations for this project can be defined differently and used in other contexts. We urge “kia tūpato” [tread carefully] when translating from one language to another; knowledge can be lost or misinterpreted.

Ngā tohutoro | References

Bishop, R. (1996). Addressing issues of self-determination and legitimation in kaupapa Maori research. In B. Webber (Ed.), He paepae korero: Research perspectives in Maori education. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Gillon, G., & Macfarlane, A. (2017). A culturally responsive framework for enhancing phonological awareness development in children with speech and language impairment. Speech, Language and Hearing, 20(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/2050571X.2016.1265738

Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Denston, A., Wilson, L., Carson, K., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2019). A better start to literacy learning: findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 32(8), 1989-2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7

Gillon, G., Smith, J. P., Maitland, R., Macfarlane, S., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2024). He awa whiria: Informing the design of the better start literacy approach. In A.H. Macfarlane, M. Derby., & S. J. Macfarlane (Eds.), He awa whiria: Braiding the knowledge streams in research, policy and practice (pp. 145–168). Canterbury University Press.

Hill, R. (2020). The pedagogical practices of Māori partial immersion bilingual programmes in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.10 80/13670050.2020.1729693

Jones, K.-L. (2023). He oranga ngākau, he pikinga waiora: Ngā tāngata marae, ngā Ngākau Māhaki : pūrākau of Puna Reo Māori teachers [Doctoral thesis, University of Canterbury]. https://hdl.handle.net/10092/105172

Justice, L. M., Meier, J. D., & Walpole, S. (2005). Learning new words from storybooks: An efficacy study with at-risk kindergartners. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(1), 17–32.

Kukutai, T., & Taylor, J. (2016). Data sovereignty for indigenous peoples: Current practice and future needs. In T. Kukutai & J. Taylor (Eds.), Indigenous data sovereignty (pp. 1–22). ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/ CAEPR38.11.2016.01

Lee, J. (2009). Decolonising Māori narratives: Pūrākau as a method. MAI Review, (2). https://journal.mai. ac.nz/system/files/maireview/242-1618-1-PB.pdf

Macfarlane, A. H., & Macfarlane, S. (2018). Toitū te mātauranga: Valuing culturally inclusive research in contemporary times. Psychology Aotearoa, 10(2), 71–76.

Macfarlane, S., Macfarlane, A. H., & Gillion, G. (2015). Sharing the food baskets of knowledge: Creating space for a blending of streams. In A. H. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane, & M. Webber (Eds.), Sociocultural realities: Exploring new horizons (pp. 52–67). Canterbury University Press.

Mamaku, T. A. (2014). Koha: More than a gift. The Wireless. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/the-wireless/371516/ koha-more-than-a-gift

May, S. (2005). Bilingual/immersion education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8(5), 365.

Ministry of Education. (2021). Māori language in schooling. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/ statistics/6040

Ministry of Education. (2024). Māori language in schooling. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/ maori-language-in-schooling#:~:text=Year,Maori%20Language%20in%20Education:

Smith, G. H. (1990). Taha Maori: Pakeha capture. In J. Codd, R. Harker, & R. Nash (Eds.), Political issues in New Zealand education. (pp. 183-197). The Dunmore Press.

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (3rd ed.) Zed Books.

Te Huia, A. (2015). Perspectives towards Māori identity by Māori heritage language learners. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 44(3), 18–28.

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. (2024). Ngāi Tahu papatipu rūnanga. https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/ngai-tahu/papatipurunanga/

Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga Ministry of Education. (2025a). Tāhūrangi—New Zealand curriculum. Te Poutāhū Curriculum Centre. https://newzealandcurriculum.tahurangi.education.govt.nz/new-zealandcurriculum/5637175326.p

Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga Ministry of Education. (2025b). Te marautanga o Aotearoa. Te Poutāhū Curriculum Centre. https://kauwhatareo.tahurangi.education.govt.nz/mi/kauwhata-reo/whata-marau/ ng-marau/te-t-rewa-marautanga-o-aotearoa/5637154333.c

Appendix 1:

Outputs

Media releases

https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/news-and-events/news/making-matauranga-maoriaccessible-to-tamariki

Smith, J. Radio interview, Making mātauranga accessible to tamariki, on 95bfm The Wire; 13th September 2023.

Reports and posters

Smith, J., Jones, K L., Scott, A., Kererū, L. (2024) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi: TLRI final report (No. 6) [September 30 2024]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2024) TLRI progress report (No. 5) [March 31 2024]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2023) TLRI progress report (No. 4) [September 30 2023]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2023) TLRI progress report (No. 3) [March 31 2023]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022) TLRI progress report (No. 2) [September 30 2022]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022, August 25-27) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi [Poster presentation] George Abbot Symposium, University of Otago Christchurch

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022) TLRI Progress Report (No. 1) [March 31 2022]

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022) TLRI intentions poster (No. 1a) [March 31 2022]

Presentations and workshops

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. Kererū, l. (2024 October 20–22) Nurturing Cultural Connections Through Literacy: Insights from Community-Based Research. International Indigenous Wellbeing Conference, Auckland New Zealand.

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2024 May 3) Community presentation: Aroha ki te tangata, te tuahiwi ki te whai ao, a pūrākau launch. Tuahiwi Marae, Tuahiwi

Smith, J., (2024 February 26) Better start literacy approach hui ā-whānau with a focus on pūrākau. Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

Smith, J. P., Scott. A. (2024 February 21) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi: staff professional development. Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

Smith, J. P., Scott. A. (2024 February 19) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi: staff professional development. Te Kura o Tuahiwi.

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2024 November 21) Staff meeting update and planning. Te kura o Tuahiwi

Smith J. P., Jones, K L. (2022 October 26-27) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi: embedding ancestral stories into literacy practices. Child Well-being Research Institute Research Symposium. University of Canterbury.

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022, May 22) Wānanga 1: ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi. Tuahiwi Marae, Tuahiwi

Smith J. P., Jones, K L. (2022 May 12) Ngā pūrākau o te kura o Tuahiwi: undertaking kaupapa Māori research. Te Rū Rangahau: Māori Research Laboratory, University of Canterbury

Smith, J. P., Jones, K L., Scott, A. (2022, March 16) Staff meeting introduction of the kaupapa and planning. Te Kura o Tuahiwi [online hui]

Articles in preparation

Scott, A., Smith, J. P., Jones, K-L. & Kererū, L. (in preparation). Enhancing Vocabulary and Oral Narrative Skills Through Systematic Vocabulary Elaboration: A Study in Māori Medium and Bilingual Classrooms.

Smith, J. P., Scott, A., Jones, K-L. & Kererū, L. (in preparation). Ngā Pūrākau o Tuahiwi: A Living Taonga Empowering Community, Identity and Research.

Jones, K., Smith, J.P., Scott, A., & Kererū, L. (in preparation). Language Revitalisation, Identity Development and Engagement through Indigenous Literacy Teaching in Māori Medium Education.

Appendix 2:

Pūrākau overview of teaching

| Week | Pukapuka title | English kupu | Te reo Māori kupu | Teaching focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matariki at Tuahiwi/Matariki ki Tuahiwi |

|

|

Listen to a story, learn new target words, discuss the story with a peer. |

| 2 | A Trip to Kaiapoi Pā/ Haerenga ki Kaiapoi Pā |

|

|

Listen to a story, learn new target words, discuss the story with a peer. |

| 3 | Kapa Haka at Tuahiwi/HineRēhia |

|

|

Listen to a story, learn new target words, learn the story grammar element of ‘character’. |

| 4 | The Pā Kids/ Taku Tipuranga |

|

|

Listen to a story, learn new target words, revise the story grammar element of ‘character’. |

| 5 | A Day with Poua Ivan/ Whanaungatanga |

|

|

Listen to a story, learn new target words, introduce the story grammar element of setting’. |

| 6 | A Trip to Kaiapoi Pā/ Haerenga ki Kaiapoi Pā |

|

|

Listen to a story, revise target words, introduce the story grammar element of ‘problem’. |

| 7 | Kapa Haka at Tuahiwi/HineRēhia |

|

|

Listen to a story, revise target words, introduce the story grammar element of ‘plan’. |

| 8 | A Day with Poua Ivan/ Whanaungatanga |

|

|

Listen to a story, revise target words, revise the story grammar elements of character, setting, problem and plan. |

| 9 | Matariki at Tuahiwi/Matariki ki Tuahiwi |

|

|

Listen to a story, revise target words, practice constructing a retell and linking the story to own experience and knowledge. |

| 10 | The Pā Kids/ Taku Tipuranga |

|

|

Listen to a story, revise target words, practice constructing a retell and linking the story to own experience and knowledge. |