Introduction

This research explores culturally grounded provisions of speech-language therapy (SLT) services for tamariki Māori with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN). (See He Kuputaka for te reo Māori terms as used in the text.) The research aims to address disparities and highlight inequities in SLT services, particularly their lack of alignment with kaupapa Māori education (KME) and te ao Māori. Over the past 2 years, a research team comprising both members and non-members of Te Aitanga-aMāhaki has worked with Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki whānau, hapū, and iwi to address these challenging disparities and inequities and understand what is needed to transform SLT practice to better support the cultural needs of tamariki Māori with SLCN in KME.

The study was prompted both by the overrepresentation of tamariki Māori in negative statistics within education and health, including SLT-related challenges (NZSTA, 2024) and by a lack of research available to guide SLT service provision for this collective of Māori education. Current SLT services often fail to reflect Māori cultural values or the unique philosophies of KME (Campbell, 2022), which include kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori, and kura ā-iwi (Ministry of Education, 2024). These gaps underline the urgency for a localised, culturally relevant approach to SLT that upholds Te Tiriti o Waitangi and honours the aspirations of whānau and hapū of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi.

Through a kaupapa Māori research methodology, this research employed nohopuku and whakawhiti kōrero, and thought space wānanga (Smith et al., 2019) hereafter referred to as wānanga, to explore experiences, needs, aspirations, and preferred tikanga for SLT practice and service provision within Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki rohenga. The findings informed the development of a guiding framework for SLTs, and a kete rauemi to support tamariki with SLCN at home and in the classroom. The study contributes to a growing body of work advocating for the decolonisation of the SLT profession, and indigenisation of SLT service provision. It emphasises the importance of culturally safe SLT services that integrate and align with both te reo Māori and mātauranga Māori to address the cultural needs of tamariki Māori with SLCN, and their whānau.

The lead researcher of this research project is a speech-language therapist and an active member of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi, bringing an insider perspective shaped by lived experience of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki reo, tikanga, and kawa; and of SLT in Aotearoa. All research team members are Māori researchers and qualified in various specialist areas, including early-intervention services, SLT, and audiology.

Background

In Aotearoa, many tamariki Māori have SLCN, yet SLT services are still not always culturally appropriate or relevant to tamariki Māori, or to KME. KME is a collective of Māori education that emphasises total immersion teaching and learning. It prioritises Māori knowledge and philosophy and is delivered outside traditional Pākehā education settings. This type of education is provided by “kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori, kura ā iwi, and wānanga” (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 3). The establishment of KME in the early 1980s was an act of resistance led by prominent Māori leaders of the time and born out of the struggles Māori communities faced regarding language loss and cultural oppression (Smith, G. H., 1997, 2003).

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, as the founding document of Aotearoa/New Zealand (hereafter referred to as Aotearoa) (Cabinet Office, 2019; Came et al., 2020; Sheridan et al., 2024) was signed in 1840 by most rangatira (chief(s)) of Aotearoa and representatives of the British Crown. Since then, Māori continue to fight for this document to be honoured by the Crown/Government (hereafter referred to as the Government) and implemented through its institutions and systems (Barnes et al., 2023). As a result of successive governments’ failure to uphold their Tiriti o Waitangi obligations, Māori are disproportionately represented in negative statistics across various sectors (NZSTA, 2019), including an overrepresentation of tamariki Māori requiring speech-language and communication support in education and health (NZSTA, 2024). Of most concern is the lack of communication support provisions available for tamariki, whānau, and KME that are culturally appropriate to hapū and iwi tikanga and kawa; culturally relevant to the different philosophies and curriculum of kōhanga reo, kura aho matua, and kura ā-iwi; and culturally safe where whānau, hapū, iwi, and KME’s ways of knowing, being, and doing are not at risk of rāwaho manipulation, alteration, or a diminishing of mauri to their educational establishments (Campbell, 2022).

In the context of SLT for Māori, Te Tiriti o Waitangi is essential for the collaborative efforts of both Māori and tangata Tiriti SLTs. It guides their commitment to decolonising the profession and protecting Māori interests by reviewing systems and processes, developing policies, and conducting kaupapa Māori research.

SLT in Aotearoa started in the early 1920s at Christchurch’s School for the Deaf. After almost 30 years of supporting the speech and language needs of New Zealanders, the New Zealand Speech Therapists’ Association (NZSTA) was established in 1946 (Communication Matters, 2021). SLTs have many responsibilities and activities, including prevention, assessment, diagnosis, and intervention in communication and in swallowing issues (NZSTA, 2024). Speech-language therapy encompasses both communication and swallowing across the lifespan, from newborn pēpi to kaumātua, addressing a wide range of complex conditions. Dysphagia, or swallowing disorders—particularly the focus on safe swallowing and the neurological factors contributing to an unsafe swallow—is likely a key reason why SLT maintains a strong clinical foundation (Kohere-Smiler et al., 2024). In 2024, just over 1,000 SLTs registered with the NZSTA are tasked with supporting the SLCN (NZSTA, 2019) of all people residing in Aotearoa. The current SLT workforce composition, of those registered with the NZSTA, consists of “90% Pākehā, 4% Māori, 1% Pasifika, and 4% Asian” (NZSTA, 2019, p. 2). The lack of Māori representation in the SLT workforce seems to be a significant factor contributing to disparities in the availability of culturally safe SLT services for tamariki and whānau Māori.

Recognising these disparities and acknowledging the importance of speech-language and communication on identity, sense of belonging, and the wellbeing of tamariki Māori (Highfield & Webber, 2021; Rameka, 2018; Ritchie & Rau, 2010), it was apparent to Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi that a localised approach was necessary to support Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki tamariki who experience SLCN. Te Reo Toiere o Māhaki (see Appendix A), a conceptual framework, was crafted as that which guides the development and implementation of initiatives and projects that focus on the SLCN of Te Aitanga-aMāhaki children. It describes a strengths-based approach to communication support, which bases its foundations within Te Wāo Nui o Tānemāhuta. Te Reo Toiere o Māhaki is a framework that celebrates diversity in language and communication, using the metaphor of manu and their unique songs to represent the distinct voices of tamariki Māori within Māori communities. Each child’s uniqueness strengthens the community. When nurtured within a supportive environment, it fosters confident self-expression. Language is vital for human connection, shaping our thoughts and interactions. Recognising commonalities and differences in language is essential for developing the communication skills of all tamariki Māori within Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi.

Traditional SLT approaches often overlook the cultural needs of tamariki Māori and fail to incorporate te reo Māori and mātauranga Māori. Therefore, Te Reo Toiere o Māhaki commits to providing culturally relevant speech-language and communication support that aligns with Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki ways of knowing, being, and doing.

Research aims and questions

There are two main aims of the research project:

- To develop a guiding framework for SLTs working with whānau and kaiako Māori who support tamariki with complex SLCN in Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi.

- To design and create Kete-Rauemi (resource pack) to support mild–moderate SLCN of tamariki at home with their whānau and in the classroom with their kaiako.

To meet these aims, we worked with whānau and kaiako Māori of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki to answer four questions:

- What do our people know about SLT and the supports available to them?

- What are our people’s dreams and aspirations for our tamariki who face communication challenges?

- How can whānau, kaiako, and SLTs work together to achieve our collective dreams and aspirations to maximise the learning potential of our tamariki experiencing SLCN?

- What information, strategies, and resources would be relevant to support tamariki with SLCN both at home and in the classroom?

Research design

Methodology

This is a qualitative kaupapa Māori research project, underpinned by kaupapa Māori theory, that promotes the validity and legitimacy of te reo Māori, mātauranga Māori, and Māori culture (Nepe, 1991; Pihama, 2010; Smith, G. H.,1997; Smith, L. T., 2015, 2017). Kaupapa Māori research has evolved from Māori communities and has succeeded in supporting fundamental changes in the Māori education, health, social development, and economic sectors we see today (Durie, 1999; Ministry of Education, 2020; Ministry of Health, 2020; Office of the Children’s Commissioner, 2020; Rua et al., 2023; Smith, G. H., 1997; Smith, L. T., 2021). Kaupapa Māori research provides the political platform for research by Te Aitangaa-Māhaki, with and for Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki people to share their knowledge through their experiences and lived realities of SLT service provision. Through kaupapa Māori research, we can describe preferred tikanga and kawa as determined by Te Aitangaa-Māhaki when conducting research related to Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki. The application of kaupapa Māori theory in this research hints at challenges and issues within current SLT service provision that have, whether consciously or unconsciously, contributed to the socioeconomic, political, and cultural disparities of Māori people (Smith, 2003). Furthermore, it addresses the inherent power relations within SLT concerning service provision for tamariki and whānau Māori.

Kaupapa Māori research requires a focus on transformation (Pihama, 2016; Smith, G. H., 2003) and therefore a strategy for intervention. Smith G. H. (2003) discusses the concept of transformative-praxis as a continuous process of conscientisation, resistance, and transformative action. Kaupapa Māori research as a non-linear, relational process has been developed and employed by Māori to challenge dominant systemic and institutional constructs that uphold the status quo (Smith, G. H., 2003). This approach confronts homogeneous ideologies of oppression and marginalisation enforced by the coloniser. Smith, G. H. states that “the counter strategy to hegemony is that Indigenous Peoples need to critically ‘conscientize’ themselves about their needs, aspirations, and preferences” (2003, p. 3). Conscientisation, as one part of the process, requires critical reflection and evaluation of thoughts, behaviours, and practices. It aims to distrupt entrenched societal ideologies that are fundamentally rooted in colonisation (Jackson, 2016). This shift in mindset is crucial for individuals and communities to move from a position of defence to one of empowerment, self-determination, and emancipation (Smith, G. H., 2003).

Participant recruitment

Potential participants were either identified through the researchers’ personal and professional networks or agreed to be contacted about future research projects during local wānanga they had previously been involved in. Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi trustees were also asked to tono for whānau and kaiako participants at their marae hui. Additionally, the lead researcher organised hui with local kura, schools, early childhood education centres, and kōhanga reo to explain the research purpose, aims and objectives, structure, and design.

To satisfy the inclusion criteria of the research, all participants were of Māori descent, and whakapapa to, or had a strong connection to, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

There was a total of 16 participants; six were whānau (either a parent or grandparent) of tamariki with SLCN who had experience with SLT services. The remaining 10 participants were kaiako.

Table 2 summarises wānanga participant types.

| Participant type | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Whānau participants | 6 |

| Kaiako Māori in kaupapa Māori education | 4 |

| Kaiako Māori in mainstream/English-medium education | 6 |

| Total participants | 16 |

Descriptive pseudonyms that reflect participant type and a numerical system are used when referring to research participants in the study. For example:

Whānau participants (n = 6): Whānau 1–6.

English-medium education (EME) kaiako (n = 6): EME, Kaiako 1–6

Kaupapa Māori education kaiako (n = 4): KME, Kaiako 7–10

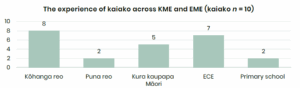

The composition of kaiako participants was diverse, enabling them to draw from their personal and professional experiences. Three critical factors characterise this composition: (1) the intersection of being a kaiako and being a parent or grandparent of a tamaiti with SLCN; (2) their experience across both KME and mainstream EME; and (3) the various roles they held throughout their careers, including kaiako, specialist teacher, and positions in management and governance.

Regarding the first critical factor, six out of 10 kaiako were also whānau members (either a parent or grandparent) of a tamaiti with SLCN. This dual role allowed them to share insights based on their personal and professional experiences with SLT service provision.

Participants themselves chose to identify as either kaiako or whānau.

Secondly, to facilitate a robust discussion of SLT service provision in KME, it was essential for kaiako participants to have experience in this area. Table 3 outlines kaiako experience across KME and EME settings.

In terms of the final critical factor regarding kaiako composition, some kaiako had experience in different roles and managed various responsibilities within their educational facility. Table 4 provides an overview of the governance roles and responsibilities held by kaiako participants throughout their careers. This diversity of roles allowed kaiako to draw insights from a wide range of experiences.

| Kōhanga reo | Puna reo | Kura kaupapa Māori | ECE | EME primary school | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiako | 8 / 10 | 2 / 10 | 5 / 10 | 7 / 10 | 2 / 10 |

| Specialist Teacher | 2 / 10 | 2 / 10 | 1 / 10 | 2 /10 | 1 / 10 |

| Management | 1 / 10 | 1 / 10 | 2 / 10 | 3 / 10 | 1 / 10 |

| Board member | 6 / 10 | 0 | 2 /10 | 0 | 0 |

* Specialist teacher = Learning support, tikanga, and reo Māori resource teachers. Management = Kōhanga manager, Centre manager, Syndicate leaders.

Design

The initial plan for this project was structured to unfold over two phases, each encompassing a series of marae- or community-based wānanga. These wānanga were aimed at capturing the insights and perspectives of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki whānau, hapū, and iwi. The objective was to develop a theory of what SLCN means for them and envision the potential future of SLT services in the area. However, unforeseen circumstances arose when a natural disaster impacted Te Aitanga-aMāhaki iwi, affecting both the research team and participants. As a result, the project’s approach required adjustments to phase two. Wānanga planned for in this phase were substituted with alternative communication methods, including emails, messaging, phone calls, and face-to-face hui, often scheduled when participants were available or spontaneously during another iwi or hapū hui or kaupapa, such as marae hui, tangihanga, and marae wānanga.

Phase one

Four wānanga were held during phase one. Table 5 describes each wānanga and its participant composition.

| Wānanga | Description of participants | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Tahi | Kaiako Māori working in mainstream English-medium settings with high Māori populations (at least 55% Māori (Infometrics, 2024)) including early childhood centres, and up to Year 3 in junior school syndicates | 4 |

| Rua | 2 | |

| Toru | Whānau of tamariki experiencing SLCN | 6 |

| Whā | Kaiako Māori of KME, including kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori | 4 |

Table 6 explains the structure of each of the four full-day wānanga. The full-day wānanga provided data relevant to all four research questions. The morning and midday sessions focused on research questions 1, 2, and 3, enabling the research team to build an evidence base for the first research aim: To develop a guiding framework for SLTs working with whānau and kaiako Māori who support tamariki with complex SLCN in Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi.

The afternoon session of the wānanga was dedicated to discussions around research question 4, which is linked to the second aim of the research: To design and create KeteRauemi to support tamariki with mild–moderate SLCN, at home with their whānau and in the classroom with their kaiako.

| Full-day thought space wānanga structure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Kaupapa | Data gathered aligned to RQ |

Linked to aim |

| Morning session |

|

1 | 1 |

| Midday session |

|

2, 3 | 1 |

| Afternoon session |

|

4 | 2 |

Phase two

Phase two focused on data analysis, writing, and verifying information with research participants. This time provided opportunities for participants to share additional relevant information. Communication methods between the research team and research participants included email, phone calls, messages, organised hui, and spontaneous gatherings at marae, hapū, iwi, community events, and other kaupapa.

| Purpose | Method of contact | Participants | Type of information | RQ | Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review guiding framework | All | Request for feedback, input comment, review. | 1, 2, 3 | 1 | |

| Guiding framework final draft check | All | Review and comment. | 1, 2, 3 | 1 | |

| Seeking clarity | Instant message | KME, Kaiako 10 | Clarify kura actions taken to mitigate inequitable learning support services for students. | 2, 3 | 1 |

| Participants’

own kaupapa |

Phone call | Whānau 1 | Clarity on service process and understanding clinical report. | 4 | 2 |

| Participants’ own kaupapa | Unplanned/ spontaneous hui (marae kaupapa) |

Whānau 1 | Sharing ideas for kete rauemi. | 4 | 2 |

Methods

Thought space wānanga (Smith et al., 2019), whakawhiti kōrero, and nohopuku were the preferred methods of ako for Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki iwi and were therefore incorporated into the design of this research as data-collection methods. Adaptations in phase two included alternative means of communication between research team and participants, such as email, phone, messaging, organised hui, and unplanned or spontaneous hui at marae, hapū, iwi, and community events.

The research team had wānanga and whakawhiti kōrero with Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki Trust Board and iwi rangatira throughout the entire project. These meetings and discussions started well before the application proposals, continued through phases one and two, and will continue beyond the project conclusion.

Ethical considerations

This research project was conducted under the tikanga and mana of Te Aitanga-aMāhaki iwi. Additionally, this research project was granted full approval by The University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC23900). All participants were provided with a Participant Information Sheet and Participant Consent Forms. All participants provided their written consent.

Analysis

All wānanga were video and audio recorded, transcribed, and identifying information was removed. During this phase, the research team employed the same methods used for data collection, including wānanga, whakawhiti kōrero, and reflection for the following kaupapa: the direction of wānanga discussions; the mauri of the wānanga and participants; the conceptual framework; and kaupapa Māori concepts that were revealed in the data. Once we understood these aspects, we then developed an initial template analysis of themes. Brooks and King’s (2014) template analysis approach allowed for flexibility and researcher workability, meaning we could cater to the intricacies of kaupapa Māori research and the nuances of te ao Māori. The initial template was developed by taking a small subset of data to identify key words and themes. Team wānanga were held to discuss themes and, once confirmed, the initial template was applied to the entire collection of data. Additional team wānanga focused on revisions to the template and important matters that arose around the themes and subthemes to reach consensus.

Findings

RQ1: What do our people know about SLT and the services available to them?

Finding 1: Participants have limited knowledge about SLT, its scope of practice, and what to look for when considering a referral for communication support.

Through wānanga, we found that whānau and kaiako of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki knew little about SLT and the support services available to them. Interestingly, most kaiako from mainstream EME were more confident to share their thoughts and experiences of SLT. They spoke of concepts such as a child’s ability to be understood by the people around them; communication involves non-verbal communication; and SLT is concerned with speech sounds and making words. In contrast, whānau participants and kaiako from KME expressed unfamiliarity with SLT until it became necessary for their tamaiti or student in the classroom, or until they participated in this research project. For example, a whānau participant described having no understanding of SLT during her initial encounters with it for her mokopuna:

I knew nothing, knew nothing on speech therapy and all of that! But I was lucky with her speech because she spent most of her upbringing in hospital and they did a lot with her in there […] when she came home things went backwards, her speech went backwards, her reading went backwards. (Whānau 2)

KME Kaiako 8 shared that she only fully understood the role of SLTs through her involvement in the research, saying, “I actually know what you two do now.” She also expressed difficulty identifying SLCN in her students due to her limited awareness, stating, “How do you help when you don’t know what to look for?”

Finding 2: The referral process and criteria for communication support through the Ministry of Education is unclear.

After probing further during wānanga, we found that all wānanga participants had an understanding that SLT was in fact a service that helped children to be understood by other people around them. However, they also expressed deep frustration with the referral process and meeting criteria to receive communication services. One kaiako in mainstream EME explained her thoughts of SLT and what she understood to be the referral process:

Well for me, it was just a name, it’s something through Ministry of Education, you had to be referred through your GP, so for me that’s all it was, it was just a name […]. When [concerns are] recognised by kaiako, we talk to the parents, so the gap is from the parent to the GP, from the GP back to the parents, it’s the processes we have to take to […] getting our names into the system you know? (EME, Kaiako 6)

We learnt that the Ministry of Education’s criteria for accessing SLT services was unclear. One whānau participant, who had children and grandchildren who were deaf or hard of hearing, expressed that, while she received a service through the adviser of deaf children, her children and grandchildren still did not meet criteria for an SLT service:

… with speech language, we got absolutely nothing. Until I got online and went to Google, I went through every speech language thing and where we could find help because their language […], they had very little language, so I swore I was going to get online and find it. (Whānau 1)

Finding 3: Participants are overwhelmed by multidisciplinary teams, contributing to confusion and frustration.

We learnt that whānau experience with multidisciplinary teams is often overwhelming and confusing. The following example also suggests that the recommendations of one team member are seen as the consensus for the entire team. In Aotearoa, SLTs are not prescribing professionals, and recommendations involving medication for users of SLT services fall outside the scope of SLT practice (NZSTA, 2012), making it unlikely that such a recommendation would come from the speech-language therapist:

Similar to you aunty, […] but when she was four, we got told that because she’s not mute, she didn’t need a speech language therapist, […]. By the time she started kura, she was just struggling so much to the point that we had so many different specialists coming in and I was having meetings with the kura pretty much every two weeks, with somebody different. […] in one meeting, I was so discouraged I was told that until she’s medicated there’s nothing they can do for her, and I was very upset by that. (Whānau 4)

RQ2: What are our people’s dreams and aspirations for our tamariki who face communication challenges?

Through this research, participants developed an understanding of SLT and its history in Aotearoa. Wānanga participants were able to make connections and draw their own conclusions about why their tamariki Māori were not consistently receiving services that were culturally responsive to their tikanga and kawa or aligned with the philosophy and curriculum of KME.

Finding 4: Accessible services that reflect Māori communities are not so accessible (accessible language).

Accessible language is fundamental to supporting both whānau and kaiako engagement and participation in SLT services. Ensuring whānau and kaiako are fully informed means they make informed decisions about the SLT services they receive. Research participants shared their negative experiences of when SLTs continue to use clinical language, highlighting how inaccessibility to relevant information resulted in low engagement and participation in SLT services, exacerbating inequity. For example, two whānau participant expressed how they felt during and after hui with SLTs:

I’m just like ‘Sorry, I don’t understand what you’re saying, can you break it down for me?’, but they still use that different language, and I’m walking away like, ‘I have no idea what you know!’ So, I have to get mum […] or somebody else to come with me to actually explain to me what it is that they’re saying because I’m always walking away […] and I feel like I’m going backwards again. (Whānau 4)

… using all those big words and all that, the other end of communication is actively listening but if you’re gonna throw that at me, I’m gonna start shutting down. I’m not listening to you, I’m done aye! (Whānau 3)

Interestingly, kaiako participants from mainstream EME were more inclined to seek clarity from specialists regarding aspects of SLT service provision, especially when they sensed that whānau were not confident to say that they did not understand. One kaiako participant spoke about her dream for young māmā and pāpā to be confident in their tuakiritanga so that they can participate in discussions and challenge specialists’ ideas when they do not align with their own”

when you’re an older mother or father, you feel more confident about your tuakiritanga and the world. But when you’re a young māmā or pāpā, you don’t feel you have that sense, so you feel like everyone around you is the specialists, but actually, you are the specialists […] ‘we know our babies better than anyone’. But not all the time do we feel confident to speak to anyone that’s not Aunty. You have to make those relationships […]. They need support, they need advocates (KME, Kaiako 2).

Finding 5: Navigating power dynamics in SLT service provision is challenging.

We learnt that power dynamics between young mātua and specialists persist and may be characterised by young mātua being afraid to seek clarity, challenge perspectives, or participate in discussions concerning their children. Building trusting “relationships” was identified as a key solution for creating safe spaces where whānau feel comfortable and confident to participate.

Research participants expressed feelings of loneliness in their new learning journey while navigating SLT services. They reflected on the positive impact that advocates, navigators, and kaiāwhina could have had on their experience to reduce frustration and making the SLT process less daunting. KME, Kaiako 9 explains her thoughts and ideas on how a navigator or kaiāwhina could support whānau through these processes:

That’s why you need that one navigator, that main person will be the one to communicate with our whānau and the kaiako. ‘This is what happened in the hui, do you agree? Disagree?’ and then you’re told what the haps is from the whānau perspective, then you take it back to the team ‘no she doesn’t want this; they don’t want that [it’s not] realistic for them’.

Finding 6: Hope for more Māori in SLT and dream of a kaupapa Māori SLT service pathway.

Through wānanga, participants came to the realisation that SLT, as it currently exists, is primarily designed for Pākehā children with SLCN, limiting its effectiveness for tamariki and whānau Māori. Furthermore, research, resource, policy, practice, and the typical SLT demographic is predominantly reflective of Pākehā perspectives, theories, ideologies, and practice, rendering them inadequate for tamariki and whānau Māori. All research participants hoped for more Māori in SLT and dreamed to have their own kaupapa Māori SLT service pathway, which is grounded in te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, and mātauranga Māori:

That’s my dream overall. Not just with this [SLT], but our own people leading everything. Providing everything for our own people; for our people, by our people, across the whole board! (Whānau 4)

My dreams and aspirations for this space are that there’s more raukura in this space, kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa Māori, wharekura. Raukura who are born into the Māori space and understand the tikanga side of it very well. […] If these raukura come out of university through these kaupapa, they go back into our schools and our centres, our tamariki will respond to them cause they look the same as them. They talk the same, they walk the same. That’s my aspiration for this place. Hopefully we get […] more brown faces on the ground. (EME, Kaiako 4)

KME, Kaiako 7: “Ka pai, you know with the help of other kōhanga and kura, hopefully we can develop our own one [SLT service pathway], that aligns with our tikanga, it aligns with everything (KME, Kaiako 9: ‘with our way of being’).”

Finding 7: Māori want to be Māori—Te Tino Rangatiratanga.

Wānanga participants expressed their aspirations for tino rangatiratanga in service provision, emphasising that Māori should be able to assert their needs and preferences by reinforcing their boundaries, values, mātauranga Māori, and tikanga practised in their homes and classrooms:

We always want the best aye, that’s our aspiration for our babies, but what does that look like? It’s us taking care of ourselves, our culture. Not being told by another culture what we [should do], how we should talk. (EME, Kaiako 2)

Kaiako in KME shared that they have established tikanga in their kura, requiring any specialists or manuhiri to attend karakia on Friday mornings. During this time, they introduce themselves and discuss their kaupapa with pakeke before observing tamariki in their kura. Kaiako of one rural kura kaupapa Māori confidently enforces this tikanga, and failure to comply will result in disengagement from the service:

That’s actually happened to me, twice, [the speech-language therapist] came to see a child in my class and I had no idea who [the speech-language therapist] was, why [the speech-language therapist] was there, so I had a yarn with [the tumuaki], and [that speech-language therapist] was cut quick-smart! (KME, Kaiako 7)

RQ3: How can whānau, kaiako, and SLT work together to achieve our collective dreams and aspirations to maximise the learning potential of our tamariki experiencing SLCN?

Finding 8: Mihimihi and whakawhanaungatanga are crucial in all engagements with Māori.

Through wānanga and providing updates at hapū and iwi hui, we were able to raise awareness of what SLT is and its history in Aotearoa. Subsequently, we learnt that wānanga and hui were the preferred methods for collaboration among the research participants. For example, when asked How can whānau, kaiako, and SLT work together? one whānau participant expressed:

It’s this! What you’re doing here […] as an example of how we work as Māori, aye, this is the first time I’ve been in this type of space because that’s how we as Māori do it, we wānanga and we hui and we hui. (Whānau 4)

The concept of whakawhanaungatanga was expressed by whānau and kaiako as an important element to Māori engagement, therefore SLTs should invest significantly in this area of service provision. Whānau want specialists to build a relationship with them and their tamariki:

If I grabbed your daughter, you know she doesn’t know me, she doesn’t know anything [about the situation] and she’s not comfortable, […] even if for the first time, could we just say hello? (Whānau 2)

Finding 9: The impact of colonisation on te reo Māori is prevalent.

Many whānau of Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki are unaware of their iwi history and the impacts of colonisation on their access to te reo Māori and mātauranga Māori. One kaiako participant expressed that, while tikanga Māori was instilled in her by her pakeke, te reo Māori and mātauranga Māori were often discouraged:

I even asked her that question. I asked her ‘Why didn’t you teach us how to speak the reo Nan?’ She said ‘I bloody doubt it! You’re not gonna, I’m not gonna teach you because we got beaten up for it’, but I remember her and Pāpā speaking behind closed doors (RA: And over the fence with Uncle and them), Yeah, kōrero Māori. (EME, Kaiako 6)

When reflecting on how colonisation has led to the loss of dialectal differences of te reo Māori, being key markers of regional and iwi identity, the same kaiako participant described her personal experience with language trauma, highlighting its profound effect on her Ngāti Poroutanga (identity as Ngāti Porou):

It’s [tikanga] ingrained in us […] like me for example, you know [I was] born and bred in the English world, the Pākehā world where we didn’t know […] like it took me ages to even learn the pepeha that we were supposed to have, and here I am ‘Ngāti Porou’ living in Māhaki doing pepeha from [Māhaki]. […] It wasn’t the one being told by your fricken koroua ‘Hey hey get back, what was your whakapapa again?’ So, I learnt from there, I learnt from that, […] taking slow steps. (EME, Kaiako 6)

Conscientisation and decolonising the mind is a work in progress and research participants are yet to understand their rights as tangata whenua under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Consequently, the effects of language trauma on parents may impact on their confidence to provide speech-language and communication support to their reo Māorispeaking tamariki with SLCN, risking their enrolment in KME.

RQ4: What information and resources would be relevant for you to support tamariki with SLCN at home, and in the classroom?

Finding 10: Critical funding investment is required for support staff in education.

When question 4 was posed during wānanga, kaiako participants overwhelmingly expressed a critical need for increased funding to hire kaiāwhina and teacher aids. Both kaiako and whānau participants also advocated for more Māori SLTs with lived experience of te ao Māori. These important findings were included and discussed in the guiding framework (Kohere-Smiler et al., 2024) under “Thoughts and Recommendations”.

Finding 11: Participants desire clear and effective information and resources.

We learnt that wānanga participants want simplified information on the referral process and an effective, easy-to-read “support services directory”. To ensure the directory is relevant and accurate, we plan to publish this information in a web-based format, including links to the websites of relevant specialists’ services.

Finding 12: Localised reo Māori resources that support speech, language, and communication development are essential.

We learnt that kaiako participants wanted resources in te reo Māori that could support the SLCN of their tamariki in their classrooms:

I don’t know how you would mark it, pūrākau, would love to have pūrākau, pukapuka around the different traditions. (KME, Kaiako 2)

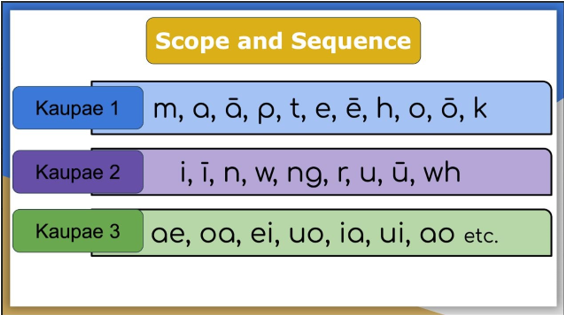

As Aotearoa transitions to providing structured literacy to all tamariki in schools and kura, this research aims to support KME facilities in the Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki region during this process. Structured literacy is an approach designed for all tamariki, but it is especially beneficial for those facing challenges with reading and writing, including tamariki who are neurodiverse including those with dyslexia (Internation Dyslexia Association, 2019).

This approach involves “systematic, explicit instruction that integrates listening, speaking, reading, and writing” (Internation Dyslexia Association, 2019, p. 6). Essential skills for reading and writing include phonemic awareness, phonological awareness, and oral language development.

Research findings 1–9 offered comprehensive insight into the perspectives of Te Aitangaa-Māhaki whānau and kaiako regarding SLT. These findings validated anecdotal assumptions that SLT is often not conducive to tamariki Māori and highlighted severe gaps in resources, culturally appropriate engagement and communication methods, and culturally responsive SLT practices.

Research findings 10–12 guided the research team in prioritising resource development based on kōrero from participants. Given the scarcity of SLT resources in te reo Māori for tamariki Māori, the scope for resource development is extensive. However, the input from whānau and kaiako about what they believe would be most valuable at this time made the prioritisation process much easier.

Research implications

Our findings highlight six research implications that the SLT profession and education system can implement to better support the SLCN of tamariki Māori in Te Aitanga-aMāhaki.

Māori resource development and educational alignment

Developing a kete rauemi specifically for whānau and kaiako is essential. It needs to be user-friendly, culturally relevant, and regularly updated to account for the evolving needs of those supporting tamariki with SLCN. Incorporating resources in te reo Māori, including pukapuka based on iwi pūrākau, will enhance its cultural significance. Additionally, the suggested pukapuka pūrākau should align with the different philosophies and curriculum of KME. As schools and kura in Aotearoa adopt structured literacy practices, access to supplementary decodable books in te reo Māori will facilitate this transition. This research collaborated with Mahi by Mahi Limited, as a te reo Māori-structured literacy expert, to design Māhaki-specific pukapuka based on their scope and sequence (see Appendix B) (Mahi by Mahi, n.d.). SLTs can support the implementation of structured literacy by assisting kura and kaiako in developing their tiered approach for tamariki requiring extra support. Furthermore, integrating speechlanguage and communication programmes in kōhanga reo, puna reo, and new entrant classrooms within kura kaupapa Māori, focusing on phonemic awareness, oral language development, and phonological awareness, will contribute to a successful transition.

Support and advocacy

There is an urgent need for increased funding to employ kaiāwhina and teacher aides, as this would significantly enhance the capacity to support tamariki with SLCN in education settings. Establishing roles for advocates or navigators within SLT frameworks can provide essential support for whānau and kaiako. These roles would facilitate communication and relationships with specialist services, ensuring whānau and kaiako feel heard and understood throughout the process.

Additionally, advocating for greater Māori representation in SLT is essential. Employing professionals who have lived experience in te ao Māori will strengthen culturally responsive practices and ensure SLT services meet the needs of Māori communities. Recruitment strategies should prioritise attracting Māori to the field of SLT, addressing both the need for representation and the provision of culturally relevant and responsive support.

Streamline processes

To improve access to SLT services for whānau and educators, it is important that we simplify the referral process and develop an easy-to-read directory of support services. Participants have expressed frustration with the current referral pathway, highlighting the need for more streamlined and user-friendly options. By addressing these barriers, we can improve engagement and outcomes for tamariki, their whānau, and their kaiako.

Creating a comprehensive support services directory will provide essential information about available resources, enabling faster access during challenging times and ultimately enhancing service delivery. Additionally, streamlining the referral process by reducing the number of steps and clarifying roles within multidisciplinary teams can help prevent confusion and frustration.

Engagement and collaboration with Māori communities

Collaboration with Māori communities is crucial for ensuring that SLT practices and resource development effectively meet the needs of tamariki Māori. Strengthening community involvement through wānanga can deepen understanding of SLT among whānau and kaiako, while regular hui create opportunities for whakawhanaungatanga and nurturing relationships. Raising awareness about SLT, its benefits, and processes through these gatherings can empower whānau to take an active role in their child’s SLT service.

Additionally, partnering with local iwi and hapū will ensure service delivery methods are co-designed to reflect Māori aspirations, tikanga, and mātauranga, which is vital for maintaining relevance and effectiveness of resources. Establishing dedicated times for evaluation and feedback during wānanga and hui will facilitate the continuous refinement of resources based on the experiences of whānau and kaiako, ultimately enhancing support for tamariki Māori.

Research, evaluation, and improvement

There is a pressing need for more kaupapa Māori research (Kohere-Smiler et al., in press) to understand important tikanga and kawa of other iwi in Aotearoa. SLTs should be aware of these practices as defined by iwi before engaging with Māori communities. This understanding can be fostered by researching the iwi in your region to gain insight into the impacts of colonisation and to acknowledge historical injustices.

Ongoing research is necessary to identify the barriers whānau Māori face in accessing SLT services and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to overcome these challenges. Additionally, advocating for policy changes that improve access to SLT services, especially for whānau Māori and those in rural areas experiencing isolation, can promote equity and lead to better outcomes for tamariki Māori.

We need to reconsider traditional/formal feedback mechanisms (such as handwritten surveys at the end of a service) and develop a more creative, innovative approach to feedback that whānau and kaiako will use to share their thoughts, experiences, and suggestions. Creative and innovative feedback loops increase the likelihood of gathering more data for analysis and reflection, ensuring that services remain responsive to Māori needs and are informed by the experiences of whānau and kaiako.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, rangatiratanga, and cultural safety

Decolonising SLT requires sustained efforts from both Māori and tangata Tiriti SLTs. It is essential for professionals in the SLT field to invest in Māori professional learning and development (PLD) to build awareness and understanding of te reo Māori, tikanga Māori, and mātauranga Māori. They must also recognise their roles as tangata Tiriti SLTs in promoting and protecting kaupapa Māori within their practice and the profession.

Developing SLT frameworks based on te reo Māori, tikanga, and mātauranga Māori, can assist in normalising SLT practice from a Māori worldview, acknowledging that speechlanguage and communication support from a Māori worldview may look different from the traditional SLT that is experienced today. By prioritising whakawhanaungatanga, wānanga, and hui as engagement methods, we align with kaupapa Māori methodology and promote a collaborative environment where whānau feel comfortable sharing their experiences. This approach enables SLTs to build awareness and respect for te ao Māori, recognising the value of mātauranga Māori within Māori communities and empowering whānau and kaiako to assert their rights regarding SLT services.

Building trusting relationships through whakawhanaungatanga is essential for ensuring that SLT services are culturally safe and responsive, centring the whānau voice in decision making and fostering a sense of agency.

Conclusion

Communication is a fundamental right of all peoples (United Nations, 1948) regardless of age, ethnicity, and ability. Tamariki Māori also have the right to receive communication support in their own language, according to their own tikanga and kawa. When SLTs understand how their day-to-day roles and activities, shaped by a non-Māori worldview, perpetuate a system that marginalises Māori through the suppression of Māori voices, lived experiences, and ways of knowing, being, and doing, the profession might then recognise the power inherent in SLT. It becomes clear that the entire profession must shift to devolve power and control to whānau, hapū, iwi, and KME, creating the space Māori need to lead and develop this sector, with tangata Tiriti SLTs supporting their leadership. The role of tangata Tiriti SLTs is to advocate for and support Māori in defining what SLT means for them. This empowerment enables transformation, where Māori create, lead, and determine speech-language and communication services that are culturally appropriate, relevant, and safe for tamariki Māori.

For tangata whenua, it is vital that wānanga and critical reflection occur to learn and understand historical injustices and their impacts on Māori wellbeing today. When this happens, a space is opened for restoration and healing. Only then can we transition into a realm of dreaming, commitment, and action (Jackson, 2020; Mercier, 2020; Ross, 2020).

He kuputaka

| ako | teaching and learning |

| hui | meeting(s) |

| kawa | ceremony, practices, protocol(s) |

| kete rauemi | resource pack |

| manu | birds |

| mātauranga Māori | Māori knowledges |

| mauri | life essence |

| nohopuku | time in reflection |

| rāwaho | outsider |

| reo | language |

| rohenga | boundaries |

| tamaiti | child |

| tamariki Māori | Māori children |

| te ao Māori | the Māori worldview |

| te reo Māori | Māori language |

| Te Wāo Nui o Tānemāhuta | the great forest of Tānemāhuta |

| tikanga | correct practices or customs |

| tono | request |

| tuakiritanga | identity |

| whakawhiti kōrero | discussion |

| whānau | family or families |

Ngā tohutoro

Barnes, A., Came, H., Dey, K., & Humphries-Kil, M. (2023). Eyes wide open: Exploring the limitations, obligations, and opportunities of privilege; critical reflections on Decol2020 as an anti-racism activist event in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 37(4), 1191–1209. https:// doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2023.2181423

Brooks, J., & King, N. (2014). Doing template analysis: Evaluating an end-of-life care service. Sage Research Methods Cases. https://doi.org/10.4135/978144627305014083342

Cabinet Office. (2019). Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi guidance. https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/ publications/co-19-5-te-tiriti-o-waitangi-treaty-waitangi-guidance

Came, H., O’Sullivan, D., & McCreanor, T. (2020). Introducing critical Tiriti policy analysis through a retrospective review of the New Zealand Primary Health Care Strategy. Ethnicities, 20(3), 434–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796819896466

Campbell, H. (2022, February 21). Te Rūnanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori o Aotearoa: Submission to Māori Affairs Select Committee Inquiry into learning support for ākonga Māori. New Zealand Parliament. https://www.parliament.nz/resource/mi-NZ/53SCMA_EVI_116502_MA7693/2d8a6e80371b18274aeda00731f 9f0ef76ea531b

Communication Matters. (2021). Commemorating 75 years of advocacy and member service. https:// speechtherapy.org.nz/assets/Uploads/STA-Communication-Matters-75-years-Timeline-Web.pdf

Durie, M. (1999). Mental health and Māori development. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00526.x

Highfield, C., & Webber, M. (2021). Mana ūkaipō: Māori student connection, belonging, and engagement at school. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-02100226-z

Infometrics. (2024). Regional economic profile: Tairawhiti. https://rep.infometrics.co.nz/tairawhiti/report

International Dyslexia Association. (2019). Structured literacy: An introductory guide. Author.

Jackson, M. (2016). Decolonising education. In J. E. Hutchings (Ed.), Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, research and practice (pp. 39–47). NZCER Press.

Jackson, M. (2020). Where to next? Decolonisation and the stories in the land. In A. Hodge (Ed.), Imagining decolonisation (pp. 133–155). Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781988545783_5

Kohere-Smiler, N., Dos Santos-Meechan, R., Malone, M., Purdy, S., & Brewer, K. (in press). Ngā manu taketake o te ao: A scoping review of research focusing on indigenous speech-language therapy for indigenous children, using indigenous methodologies. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples.

Kohere-Smiler, N., Malone, M. L., Purdy, S., & Brewer, K. (2024). Te koekoe o te tūī: A guiding framework towards indigenizing speech, language, communication support for tamariki–mokopuna of Te Aitanga-aMāhaki iwi. The University of Auckland. https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.25778589.v1

Mahi by Mahi. (n.d.). Mahi by Mahi: Empowering people to achieve their dreams. https://mahibymahi.co.nz/

Mercier, O. (2020). What is decolonisation? In A. Hodge (Ed.), Imagining decolonisation (pp. 40–82). Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781988545783_2

Ministry of Education. (2020). Implementing ka hikitia. Author. https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/ overall-strategies-and-policies/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia/ka-hikitia-ka-hapaitia-the-maori-educationstrategy/#actions

Ministry of Education. (2024). Te tira hou: Kaupapa Māori and Māori medium education networks. Author. https://assets.education.govt.nz/public/Documents/News/Te-Tira-Hou-2024.pdf

Ministry of Health. (2020). Whakamaua: The Māori health action plan 2020–2025. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/whakamaua-maori-health-action-plan-2020-2025-a3.pdf

Nepe, T. M. (1991). Te toi huarewa tipuna: Kaupapa Māori, an educational intervention system. [Master’s thesis, The University of Auckland]. http://hdl.handle.net/2292/3066

New Zealand Speech Therapists’ Association. (2012). Scope of practice. https://speechtherapy.org.nz/ membership/membership-5/

New Zealand Speech Therapists’ Association. (2019). Communication and swallowing disabilities in New Zealand data fact sheet. https://speechtherapy.org.nz/assets/Uploads/SLT-Business-Case-2024/Communication-and-Swallowing-Disabilities-in-New-Zealand-Data-Fact-Sheet.pdf?vid=4

New Zealand Speech Therapists’ Association. (2024). NZSTA business case. https://speechtherapy.org.nz/ assets/Uploads/SLT-Business-Case-2024/8213-Speech-language-therapy-BC-2024-.2-4.pdf

Office of the Children’s Commissioner. (2020). Te kuku o te manawa: Moe ararā! Haumanutia ngā moemoeā a ngā tupuna mō te oranga o ngā tamariki. https://www.occ.org.nz

Pihama, L. (2010). Kaupapa Māori theory: Transforming theory in Aotearoa. He Pukenga Kōrero, 9(2), 5–14.

Pihama, L. (2016). Positioning ourselves within kaupapa Māori research. In J. E. Hutchings (Ed.), Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, research and practice (pp. 101–113). NZCER Press.

Rameka, L. (2018). A Māori perspective of being and belonging. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 19(4), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949118808099

Ritchie, J., & Rau, C. (2010). Poipoia te tamaiti kia tū tangata: Identity, belonging, and transition. Early Years, 30(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.486048

Ross, M. (2020). The throat of Parata. In A. Hodge (Ed.), Imagining decolonisation. (pp. 21–39). Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781988545783_1

Rua, M., Hodgetts, D., Groot, S., Blake, D., Karapu, R., & Neha, E. (2023). A kaupapa Māori conceptualization and efforts to address the needs of the growing precariat in Aotearoa New Zealand: A situated focus on Māori. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 62(Suppl 1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12598

Sheridan, N., Jansen, R. M., Harwood, M., et al. (2024). Hauora Māori—Māori health: A right to equal outcomes in primary care. International Journal for Equity in Health, 23, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-02071-6

Smith, G. H. (1997). The development of kaupapa Māori: Theory and praxis. [Unpublished doctoral thesis, The University of Auckland].

Smith, G. H. (2003, December). Kaupapa Māori theory: Theorizing indigenous transformation of education and schooling. Paper presented at the Kaupapa Māori Symposium NZARE/AARE Joint Conference, Auckland.

Smith, L. T. (2015). Kaupapa Māori research—some kaupapa Māori principles. In L. Pihama & K. South (Eds.), Kaupapa rangahau—a reader: A collection of readings from the Kaupapa Maori Research Workshop Series (pp. 46–52). Te Kotahi Research Institute.

Smith, L. T. (2017). Towards developing indigenous methodologies: Kaupapa Māori research. Critical conversations in kaupapa Māori, 1(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_30-1

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (3rd ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350225282

Smith, L., Pihama, L., Cameron, N., Mataki, T., Morgan, H., & Te Nana, R. (2019). Thought space wānanga—A kaupapa Māori decolonizing approach to research translation. Genealogy, 3(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040074

United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universaldeclaration-of-human-rights

Research team

Nicky-Marie Kohere-Smiler (Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Ngāti Porou, Tūhoe, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) is one of very few Māori speech-language therapists of Aotearoa and is an iwi-based researcher with Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki Research Unit, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki Trust. She is fluent in te reo Māori me ōna tikanga and has practised as an SLT in Te Tairāwhiti since 2014. Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki is her ūkaipō and she has strong interests in supporting tamariki, whānau, and kaiako of Te Tairāwhiti and Aotearoa, who face challenges with speech-language and communication. Her research focuses on Māori speech, language, and communication support in education.

Marie Malone (Ngāti Porou) is a research assistant with Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki Research Unit, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki Trust. She has been involved in the education sector for over 20 years. Marie started her career as kaimahi for kōhanga reo and then moving into the early childhood sector and special education sector as an early-intervention teacher. Marie has extensive knowledge of the theory and practice of Te Whāriki and Te Whatu Pōkeka (A Kaupapa Māori Assessment for Learning).

Ryan Dos Santos-Meechan (Te Whakatōhea) is a research assistant in this project. He is a speech-language therapist and a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Science, Psychology at The University of Auckland.

Dr Karen Brewer (Te Whakatōhea, Ngai Te Rangi) is a leading kaupapa Māori researcher in the field of SLT. As well as successfully completing a PhD and postdoctoral research fellowship, she has experience in kaupapa Māori community-based research (Te Tino Rangatiratanga o te Mate Ikura Roro—funded by Brain Research New Zealand).

Professor Suzanne Purdy (Te Rarawa, Ngai Takoto) collaborates with many SLT, audiology, and psychology researchers to investigate communication difficulties in children. Suzanne is a co-director of Eisdell Moore Centre for Hearing and Balance Research and leads the Mātauranga Māori Module and is a member of executive for the Te Tītoki Mataora HealthTech Capability Programme. She was previously head of the School of Psychology at The University of Auckland.

Appendix A: Te Reo Toiere o Māhaki: A conceptual framework

Appendix B: Scope and sequence

(provided by Mahi by Mahi Ltd)